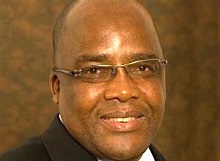

A Business Day editorial says that Health Minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi's selective use of statistics is a classic case of a politician under fire trying to present the glass as half full.

A Business Day editorial says that Health Minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi's selective use of statistics is a classic case of a politician under fire trying to present the glass as half full.

The public health system has been racked by one scandal after another. More than 144 state mental health patients died in the Life Esidimeni tragedy, over 200 people perished in the recent listeriosis outbreak and the lack of oncology services in KwaZulu-Natal has left countless patients without life-saving treatment.

Yet, says the editorial, Motsoaledi is adamant there is no crisis. In a hastily convened media conference on Tuesday of last week, he assured the nation that the health system – while hugely overloaded, with long waiting times and diminishing quality in some places – was not collapsing. The public sector was providing 4.2m people with HIV medication, treating 300,000 tuberculosis patients and dispensing chronic medicines to 2.2m patients at sites away from hospitals to reduce overcrowding, he said. These achievements, he said, were not the hallmark of a collapsed system.

The editorial says his selective use of statistics is a classic case of a politician under fire trying to present the glass as half full. He told only part of the story of the public health system and ignored the desperate reality facing far too many citizens. His words and numbers of the great successes in treatment were of little comfort to all failing to get the care they need: if the province in which you happen to live has no oncologists and your child with cancer is sent home to die, what use to you are these numbers?

The key statistic that indicates how well a health system is providing care is its institutional mortality rate, which reflects deaths among women during and shortly after childbirth. It stood at 140 in 2014, according to the most recent Saving Mothers report from the National Committee on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, double the sustainable development goal target of 70 per 100,000 live births. The report found more than half these deaths could have been prevented if women had received better care.

There is more bad news in the latest inspection report from the Office of Health Standards Compliance: only five of the 696 facilities it inspected in 2016-17 scored 80% or more, its threshold for compliance with its norms and standards. While these inspections do not measure clinical outcomes such as hospital-acquired infections or mortality rates, they nevertheless provide a useful lens through which to view the state of hospitals and clinics. The inspections were repeated in facilities that scored less than 50. The office found that many hospitals, clinics and community health centres had deteriorated over time.

The editorial says clearly not every public healthcare institution is failing and many do sterling work, but far too many do not make the grade. Far too many patients get too little, too late, or nothing at all.

When Motsoaledi became health minister in 2009, the editorial says he was frank about the problems confronting the sector. He inherited a 10-point plan crafted by the Development Bank of Southern Africa that included overhauling the health sector’s management, improving the quality of public health services and introducing universal healthcare cover under the banner of National Health Insurance (NHI). He consistently emphasised the need to improve the quality of public healthcare services in order to implement NHI, recognising it could not be bolted onto a broken system. Over time his narrative has shifted and he increasingly emphasises the importance of introducing NHI, implying it is the solution for all that ails the public sector.

But, the editorial says, the NHI will not stop the corruption, fraud and mismanagement that have riven far too many provincial health departments, evidenced by five of them receiving qualified audits in 2016-17. The editorial says Motsoaledi rightly emphasises that the Constitution stops him from interfering in provincial matters, because it delegates the power to design policy to the national department and gives the responsibility for service delivery to the provinces and municipalities. Clearly this is too big a problem for the minister to solve alone. But the admission that there is a crisis would be the first step to fixing it.

One specialist has wondered if too many “centres of power” were making it difficult to coordinate decisions and hold anyone accountable in the health crisis. “It is probably an issue of too many people making decisions that don’t correlate,” said Dr Ebrahim Variava, a Wits University professor and internal medicine specialist at Klerksdorp’s Tshepong Hospital in a City Press report.

“With so many centres of power, who do we ultimately hold accountable? Where does the buck stop? Is it with the MECs, the heads of departments or the minister?” He said there had been a “major crisis” for months before the national health department took action.

“Some hospitals seem to be privileged, and the further away you go from the areas of privilege, your issues don’t strike anyone until they’re beyond boiling point.”

The report says during the strike last month, hospital theatres had to be shut down, despite operations having been scheduled. At Taung District Hospital, doctors reported that there were no staff to feed patients, while Zeerust Hospital was completely shut down for weeks due to the volatility.

Last week, Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital saw the same disruptions as members of the National Education Health and Allied Workers’ Union trashed hospital corridors. They pushed patients out of the pharmacy and casualty sections in their protest to demand they get their unpaid bonuses. The union’s other grievances included alleged corruption and problems with procurement.

“The whole health system is critically ill and needs major resuscitation,” Variava said. He added that some form of meeting, such as a “health truth commission”, was needed to identify the problems.

The report says it has been a little over a month since the ailing North West Health Department was put under administration, but health professionals are still scrambling to reduce backlogs in surgeries and mitigate the consequences of chronically ill patients not receiving their medication on time. “We’ve had a few diabetic patients admitted due to complications and a few patients have come in with epileptic fits,” he said.

Hospitals and clinics may have reopened but the report says, just as concerned and frustrated doctors had warned, the most vulnerable people had borne the brunt of the strike.

Variava called on the SA Human Rights Commission to investigate alleged human rights violations during the strikes. “All the issues that plagued the system before the strike still exist. We still have Telkom bills that haven’t been paid, to the extent that our phone lines were cut off last week, and doctors couldn’t make outgoing calls to other facilities on landlines.”

[link url="https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/editorials/2018-06-08-editorial-nhi-is-no-public-health-panacea/"]Business Day editorial[/link]

[link url="https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/does-sa-need-nine-health-mecs-20180609"]City Press[/link]