Bruising caused by physical abuse is the most common injury to be overlooked or misdiagnosed as non-abusive before an abuse-related fatality or near-fatality in a young child. A refined and validated bruising clinical decision rule (BCDR), called TEN-4-FACESp, which specifies body regions on which bruising is likely due to abuse for infants and young children, may improve earlier recognition of cases that should be further evaluated for child abuse.

"Bruising on a young child is often dismissed as a minor injury, but depending on where the bruise appears, it can be an early sign of child abuse," said lead author Dr Mary Clyde Pierce, a paediatric emergency medicine physician and the research director for the division of child abuse paediatrics at Ann & Robert H Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, and professor of paediatrics and preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. "We need to look at bruising in terms of risk. Our new screening tool helps clinicians identify high-risk cases that warrant evaluation for child abuse. This is critical, since abuse tends to escalate and earlier recognition can save children's lives."

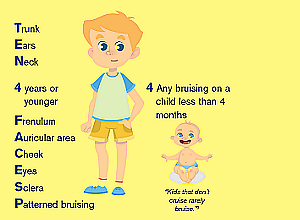

According to the study findings, the bruising screening tool TEN-4-FACESp reliably signals high risk for abuse when bruising appears on any of the following regions. "TEN" stands for torso, ear, and neck. "FACES" specifies facial features — frenulum (skin between upper lip and the gum, lower lip and the gum, and under the tongue), angle of jaw, cheeks (fleshy), eyelids, and subconjunctivae (red bruise on white part of the eye).

The "p" is for patterned bruising, when, for example, bite marks or the shape of the hand is visible on the child's skin. The "4" represents any bruising anywhere to an infant 4.99 months of age or younger. Importantly, the rule only applies to children with bruising who are younger than 4 years of age. This screening tool is a refined version of TEN-4, previously developed by Pierce.

In the study, Pierce and colleagues screened for bruising in over 21,000 children younger than 4 years of age at five paediatric emergency departments. They enrolled 2,161 patients with bruising. Researchers found that the TEN-4-FACESp screening tool had a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 87%, which means that it distinguished potential abuse from non-abuse with high level of accuracy.

"It was very important to us to make sure that the screening tool captures potential abuse without over-capturing innocent cases of children with bruising caused by accidental or incidental injury," said Pierce. "We are excited that it proved to be highly-reliable, and it is simple enough to be applied during any clinical encounter. A skin exam in infants and young children is essential."

The evidence behind the TEN-4-FACESp BCDR will soon be available as an app developed by Pierce and co-author Kim Kaczor, expected to launch by October 2021. The app will present a rotatable 3-D image of a child's body. When a clinician clicks on an area of a patient's bruise, a summary of study results will appear that allows comparison of the clinicians patient with the actual data from this large scale study with the goal of helping the user decide whether the bruise is a red flag for abuse. The app is in no way meant to supplant judgment but to provide evidence-based guidance to inform decision making.

Pierce cautions that TEN-4-FACESp is not negative for abuse in children without bruising. It is simply not relevant in those circumstances and other methods of identifying abuse would be needed.

Study details

Validation of a Clinical Decision Rule to Predict Abuse in Young Children Based on Bruising Characteristics

Mary Clyde Pierce, Kim Kaczor, Douglas J Lorenz, Gina Bertocci, Amanda K Fingarson, Kathi Makoroff, Rachel P Berger, Berkeley Bennett, Julia Magana, Shannon Staley, Veena Ramaiah, Kristine Fortin, Melissa Currie, Bruce E Herman, Sandra Herr, Kent P Hymel, Carole Jenny, Karen Sheehan, Noel Zuckerbraun, Sheila Hickey, Gabriel Meyers, John M Leventhal

Published in JAMA Network Open on 14 April 2021

Abstract

Importance

Bruising caused by physical abuse is the most common antecedent injury to be overlooked or misdiagnosed as nonabusive before an abuse-related fatality or near-fatality in a young child. Bruising occurs from both nonabuse and abuse, but differences identified by a clinical decision rule may allow improved and earlier recognition of the abused child.

Objective

To refine and validate a previously derived bruising clinical decision rule (BCDR), the TEN-4 (bruising to torso, ear, or neck or any bruising on an infant <4.99 months of age), for identifying children at risk of having been physically abused.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted from December 1, 2011, to March 31, 2016, at emergency departments of 5 urban children’s hospitals. Children younger than 4 years with bruising were identified through deliberate examination. Statistical analysis was completed in June 2020.

Exposures

Bruising characteristics in 34 discrete body regions, patterned bruising, cumulative bruise counts, and patient’s age. The BCDR was refined and validated based on these variables using binary recursive partitioning analysis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Injury from abusive vs nonabusive trauma was determined by the consensus judgment of a multidisciplinary expert panel.

Results

A total of 21 123 children were consecutively screened for bruising, and 2161 patients (mean [SD] age, 2.1 [1.1] years; 1296 [60%] male; 1785 [83%] White; 1484 [69%] non-Hispanic/Latino) were enrolled. The expert panel achieved consensus on 2123 patients (98%), classifying 410 (19%) as abuse and 1713 (79%) as nonabuse. A classification tree was fit to refine the rule and validated via bootstrap resampling. The resulting BCDR was 95.6% (95% CI, 93.0%-97.3%) sensitive and 87.1% (95% CI, 85.4%-88.6%) specific for distinguishing abuse from nonabusive trauma based on body region bruised (torso, ear, neck, frenulum, angle of jaw, cheeks [fleshy], eyelids, and subconjunctivae), bruising anywhere on an infant 4.99 months and younger, or patterned bruising (TEN-4-FACESp).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, an affirmative finding for any of the 3 BCDR TEN-4-FACESp components in children younger than 4 years indicated a potential risk for abuse; these results warrant further evaluation. Clinical application of this tool has the potential to improve recognition of abuse in young children with bruising.

Children with disabilities are at least three times more likely to experience abuse and neglect compared to their peers, and a new American Academy of Pediatrics report underscores the role of paediatricians in preventing maltreatment and offers guidance on how they can support families, reports Stat News.

“I’m always struck by the numbers of kids that are abused, and how prevalent abuse (is) in the population of children with disabilities,” said Lori Legano, the director of Child Protection Services at NYU Langone Health’s department of paediatrics and the lead author of the report.

Legano said the report allows busy paediatricians, especially those without specific expertise on child maltreatment or disability, to be more aware of the increasingly well-documented issue and approach it in an informed and sensitive way. The report looked broadly at disability in children and adolescents as “any significant impairment in any area of motor, sensory, social, communicative, cognitive, or emotional functioning.”

The majority of child maltreatment is neglect, and it is even more prevalent among children with disabilities, the report states. Children with less severe conditions, such as some intellectual and learning disabilities, may be at an even greater risk for abuse. “It could be that if they have a less severe disability, the parent might not have accurate expectations of what they can do,” Legano said. For instance, a child may not follow directions or respond to discipline the way a parent expects, leading to frustration.

The report also details associations that studies have found between certain disabilities and abuse: Children with mild cognitive impairment may be at an increased risk for physical abuse, while children with psychological or speech disorders might be at greater risk of emotional abuse. Nonverbal children and children with hearing loss may be at a greater risk for sexual abuse.

Eileen Costello, chief of ambulatory paediatrics at Boston Medical Centre, said the report offers helpful context for her practice, particularly since she sees a number of patients with hearing loss. “I’m very happy to know that I should have my radar up even more to make sure that they’re being cared for adequately and that their needs are being met,” said Costello, who was not involved in the report.

The report set out seven guidelines for paediatricians like Costello who might care for children with disabilities to help prevent and recognize abuse. The recommendations emphasise being alert for signs of maltreatment, working to address issues of family stress, establishing reasonable expectations that a parent or caretaker should have of a child’s abilities, and providing access to community resources. They also emphasise that paediatricians know the procedure for reporting child abuse, which varies by state.

“It’s shocking how states are so different,” said Shelly Flais, a primary care paediatrician in Naperville, Illinois, and a spokesperson for the AAP.

An inherent problem in identifying abuse is that due to communication difficulties, some children with disabilities who experience abuse might be unable to report it, said Heather Forkey, the division director of the child protection programme at UMass Memorial Medical Centre who helped review the paper as a liaison from its council on foster and adoptive care.

“There could be a huge amount of neglect going on for a child who’s nonverbal that we would never know about,” she said.

Pam Nourse, the executive director of the Federation for Children with Special Needs, an organisation that provides information and support to those who care for children with disabilities, said she thinks it is especially important for paediatricians to be “considering the family system as a whole.” She said that families of disabled children can be under a lot of stress, including navigating the complex systems necessary for their child’s care. That stress combined with a lack of resources can increase the risk of abuse.

Flais said she fears the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many of these stresses. “Then you’re all in a home together,” she said. “So, there’s unfortunately lots of situations that can lead to the maltreatment of children.”

If paediatricians find any evidence that abuse has occurred, they are required to immediately report it to Child Protective Services. But Costello said she tries to support families with disabled children by having conversations about appropriate expectations, parenting, and discipline so that it never gets to that point.

“Nobody starts out thinking that they’re going to be abusing their children,” she said. “We have a lot of opportunities to talk about this before it becomes an issue.”

Study details

Maltreatment of Children With Disabilities

Lori A Legano, Larry W Desch, Stephen A Messner, Sheila Idzerda, Emalee G Flaherty,

Published in Pediatrics in April 2021

Abstract

Over the past decade, there have been widespread efforts to raise awareness about maltreatment of children. Pediatric providers have received education about factors that make a child more vulnerable to being abused and neglected. The purpose of this clinical report is to ensure that children with disabilities are recognized as a population at increased risk for maltreatment. This report updates the 2007 American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report “Maltreatment of Children With Disabilities.” Since 2007, new information has expanded our understanding of the incidence of abuse in this vulnerable population. There is now information about which children with disabilities are at greatest risk for maltreatment because not all disabling conditions confer the same risks of abuse or neglect. This updated report will serve as a resource for pediatricians and others who care for children with disabilities and offers guidance on risks for subpopulations of children with disabilities who are at particularly high risk of abuse and neglect. The report will also discuss ways in which the medical home can aid in early identification and intervene when abuse and neglect are suspected. It will also describe community resources and preventive strategies that may reduce the risk of abuse and neglect.

Ann & Robert H Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago material

JAMA Network Open study (Open access)