The Mews, a father-son team of British orthodontists, have a controversial and derided theory about the source of crooked teeth, writes William Brennan for The New York Times Magazine. It's rapidly earning them a cult following in the darker corners of the internet.

John Mew is a 91-year-old orthodontist. Nothing concerns Mew more than the proliferation of ugly faces, which he considers a modern epidemic. For the past 50 years, he has championed an unorthodox cure, based on a theory about the cause and treatment of crooked teeth, which he calls “orthotropics”. If correct, Mew’s theory would upend many of the fundamental beliefs of mainstream orthodontic practice.

Traditional orthodontic teaching explains crooked teeth mostly through genetics. Mew does not believe this. Instead, he sees crooked teeth as a symptom of a sweeping, unrecognised health crisis.

Changes in our lifestyle and environment since the 18th century, Mew contends, are inducing our jaws to grow small and recessed. The teeth do their best to come in straight, but our misformed faces cause them to twist and turn and compete for space. As a result, we’ve been robbed not only of tidy smiles but also, Mew says, of the well-defined faces that were the birthright of our ancient ancestors.

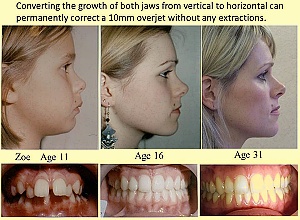

Since the late 1970s, Mew — later joined by his 51-year-old son and fellow orthodontist, Mike — has treated patients in his practice in the London suburbs. Using nothing more than palatal expanders, dietary changes, the force of the tongue and an appliance the family invented called the Biobloc, the Mews claim that they can counteract the effects of modernity while children are still growing. Where traditional orthodontists focus most of their efforts on straightening teeth, Mew says his aim is to “save the face.”

The Mews have enraged the orthodontic community with the caustic, uncompromising way they’ve promoted their theories. They and the coterie of nontraditional practitioners who follow them often occupy the furthest reaches of the orthodontic fringe, written off for decades as a small but troublesome band of cranks and kooks.

They almost never speak at mainstream conferences. Their papers, if they publish them, tend to appear in obscure, fourth-rate journals or profit-driven industry magazines. British and American orthodontic researchers told me that nearly every claim the Mews have put forth is wrong. Kevin O’Brien, a leading academic orthodontist in the UK, described their work to me as “mostly discredited.”

To the orthodontic community’s frustration, however, the Mews’ beliefs have begun filtering into the public consciousness. Exiled from academia, John and Mike have taken to spreading orthotropics online, particularly on their YouTube channel. In the process, they’ve become popular among incels, the “involuntary celibate” young men who congregate online and who explain their lack of romantic success through a toxic and misogynistic ideology.

As the incels touted the Mews, elements of the alt-right joined in, all of them sharing theories about idealised male beauty that closely overlap with the Mews’ own. In 2018, after years in obscurity, orthotropics (rebranded by incels as “mewing”) leapt into the mainstream, the subject of discussion on alternative-health forums and beauty vlogs. Mike and John’s YouTube videos have now drawn in millions of viewers, a substantial percentage of them young women.

In virality, the Mews have lost some control of their idea. On YouTube, vloggers with hundreds of thousands of followers have promoted orthotropics — a therapy intended only for young children — as a beauty treatment for adults. The Mews have responded not by telling their newfound fans they’re wasting their time, but by beginning to treat a select group of adult patients to “see what’s possible,” as Mike told me.

Since his youth, John Mew has obsessed over what distinguishes beautiful faces from plain ones. After dental school, in the 1950s, John worked as an assistant to an orthognathic surgeon, who advanced people’s jaws to improve their appearance. He told me that he would examine specimens in museums, and from this he deduced that jaw deficiencies and malocclusion — a misaligned bite — were nonexistent in the archaeological and animal records.

And so he began to think about what had given rise to them, and how they might best be cured. He trawled the literature for forgotten theories on facial growth. He obtained access to cadaver skulls and analysed them, with particular focus on what he sees as the face’s most important bone: the maxilla.

We tend to talk about the “jaw” in the singular; the image in our mind is of the lower jaw — the mandible — and it’s not hard to understand why. The mandible is the face’s mobile bone, opening and closing whenever we chew, speak, yawn, sing. By contrast, we see the upper jaw — the maxilla — as a fixed part of the skull that simply holds the upper teeth. But the maxilla is actually a separate bone of its own. And in our earliest years of life, the maxilla is hardly more connected to the skull than any other facial bone — a fact upon which Mew became fixated.

He came to believe that nearly all malocclusions, even the most severe overbites, were an illusion — the main deficiency lay not in the mandible, as the orthodontists attested, but in the maxilla. “The orthodontists assumed that, because the mandible looks like it’s back, then the maxilla must be in the correct position,” Mew told me.

But the jaws grow as a pair, their relative positions partly determined by the placement of the upper teeth. Any deficiency in the lower jaw, Mew believes, is actually a side-effect of a less obvious deficiency in the upper jaw. In Mew’s telling, this is how modern faces begin to degrade. If the maxilla doesn’t grow forward or wide enough, the mandible adjusts backward and down, so that the chin recedes and the face appears to lengthen.

An undersize maxilla will not push the cheekbones to full prominence, according to Mew, and bags may crop up under the eyes; the cartilage of the nose, lacking support, may hinge downward on the nasal bone, making the nose seem large and “hooked.” Over all, Mew says, the face will be not only plain, but in many cases so flat as to look “melted.”

Mew thought the origins of poor growth could be found in the Industrial Revolution. The rise of processed foods softened diets to the point that the masseter muscles barely had to do any work when chewing. Without the strain of the facial muscles working against the mandible and maxilla, children’s bones no longer grew as thick as they once had. And even more important, in Mew’s eyes, as people moved into cramped, polluted cities, they developed allergies that stuffed their noses and led them to breathe through their mouths, which Mew believes distorted their jaws.

Mew felt the cure, then, must lie with a diet of hard foods, and with the tongue, which he says should sit at rest in the roof of the mouth, acting as a kind of muscular scaffold for the growing maxilla. If he could figure out a way to get young patients to toughen up their diets and keep their lips shut while they were still growing, he thought he could cure malocclusion without braces.

Throughout the 1970s, he tested his theories on his own children.

In 1981, John published his theory in The British Dental Journal, hoping to spur an orthodontic revolution. But the response was frigid. Five years later, still indignant over the article’s rejection, he detailed his ideas in a self-published book, on the cover of which he printed a gold-embossed Italian quotation: “Eppur si muove” — “and yet it moves,” the defiant words Galileo is said to have spoken following his trial for heresy.

He then gave up traditional dentistry and committed himself to orthotropics full time. For the next 30 years, he treated a small but loyal group of patients at his unassuming clinic in the south London suburb of Purley — only stepping down in 2017, at age 89, when the General Dental Council took away his license.

John told me the revocation stemmed from a deliberately provocative advertisement he had published, which accused the orthodontic community of perpetrating “an illegal scam” on patients with their treatments. But he had also been accused of failing to protect a patient’s personal information and of malpractice, which I pointed out.

In his 30s, after an aimless decade partying around Europe and working as a traditional dentist, Mike decided to follow in his father’s footsteps. He trained in orthodontics in Denmark and soon joined John at the Purley clinic. Since 2018, under his direction, interest in the clinic has exploded, most of it driven by the rise in viewership for his YouTube videos.

In many of his videos, he wears blue scrubs, lending him a clinical authority; even when the words are carefully scripted, he keeps his tone natural to ensure the material is accessible. With the help of a small team, he and John began regularly putting out videos meant to show viewers the threats to health and beauty they see in traditional practice, warning them that their lives could be ruined by the decision to sit in an orthodontist’s chair.

During my week at the clinic, hundreds of emails flooded in, most of them from YouTube viewers seeking advice on tongue posture. Demand for John’s typo-riddled 2013 magnum opus on orthotropics, The Cause and Cure of Malocclusion, meanwhile, has skyrocketed.

When I spoke to traditional orthodontists about the Mews’ claims, they were universally annoyed that these ideas were catching on with the public. Some were scandalised that John, who is not an academic, signs his correspondence with the title “professor” — an honorific he has claimed since holding a two-year visiting professorship at a university in Romania. (He has also identified himself as “the clinical director of the London School of Facial Orthotropics”; the school’s campus comprises a bare conference room on the second floor of the Purley clinic.)

The orthodontists stressed that no one had ever conducted a credible study of orthotropics, and so all of the Mews’ claims of its efficacy were unproved. They pointed to studies that they said showed that treating patients young does not lead to better outcomes. They laughed at John’s obsession with the tongue and the maxilla. But they also admitted, cautiously, that the field hadn’t properly answered important questions, leaving space for the Mews’ contrarian theories to gain purchase among people who’d found traditional treatment unsatisfying.

In the early days of orthodontics, debate raged over what the focus of the field should be. Some practitioners aimed simply to straighten the teeth, while others argued that orthodontists should look beyond the mouth and try to shape the face as a whole. In 1900, Edward Angle, the father of modern orthodontics, drew a connection between malocclusion and good looks: “One of the evil effects of malocclusion is the marring or distorting of the normal facial lines,” he wrote, describing the “vacant look” and “undeveloped nose and adjacent region of the face” he saw in many patients. The tongue and cheeks, Angle hypothesised, played a powerful part in achieving orthodontic “balance”.

But other orthodontists saw it differently, believing that the most they could do was extract teeth and then straighten the smile. The debate largely ended in the 1930s, when clinicians began inventing the first cheap, reliable braces — methods of aligning the teeth that were so effective they induced a kind of awe in British and American practitioners, and mostly sidelined the proponents of facial-growth orthodontics.

In the rush to fix people’s smiles, however, troublesome facts about straightening teeth were minimised or ignored — most significant, orthodontia’s astounding rate of relapse. From the early 1960s to the early 2000s, researchers at the University of Washington collected records from more than 800 patients who’d had their teeth straightened to see how they had fared. Orthodontists had long assumed that patients’ teeth shifted slightly but then “stabilised” after the braces came off.

But the researchers were shocked to find that fully two-thirds of patients’ teeth went crooked again after treatment. When I asked Robert Little, a co-author on those studies, why so many people relapsed, he said orthodontists didn’t fully know.

A few experts granted that the Mews might be getting certain things right. Mani Alikhani, a lecturer at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine and an advocate for scientifically backed orthodontics, noted that issues like rampant relapse rightly sapped credibility from mainstream clinicians. While he thought the Mews’ views were oversimplified, he credited them and their followers with something he considered valuable: calling attention to the role of the lips, tongue and cheeks in shaping the facial bones, which he said had gone understudied. T

Timothy G Bromage, an expert on the biology of human facial development at NYU College of Dentistry, told me that, in his experience, most orthodontists’ education in the science of jaw growth is “woefully incomplete.” During growth, “the lower jaw follows the upper jaw,” Bromage said, so John Mew’s focus on the maxilla made sense.

When the Mews point to high relapse rates and certain other orthodontic shortcomings — like the way braces can damage dental roots — they stand on solid ground. But they are also quick to step onto much shakier territory, particularly in their beliefs about beauty standards. Both John and Mike have spoken extensively on their theories about the facial angles and symmetries they consider most aesthetically pleasing. They do not believe beauty is culturally determined, instead proposing that all humans have an inborn preference for wide, forward-grown faces.

Over the past several years, the Mews have begun posting videos that emphasise a new claim, which they believe is among the most serious medical discoveries in history: Forward facial growth, they say, can increase the size of the upper airway, preventing sleep apnea and its deadly secondary afflictions.

People thought he could magically fix their jaws, he said, but “I’m no more than a personal trainer.” They had to be motivated to achieve health and beauty for themselves. If someone didn’t comply, Mike would know: The Biobloc device has a data-collecting heat sensor that lets him see, on a computer chart, how many hours his patients spend wearing it.

This emphasis on compliance irks the Mews’ critics almost more than anything else, because it allows them to blame their patients for any failures, while taking credit for all successes.

Leaving [the Mews home] that [final] evening in the waning springtime light, I already knew how I felt about some of the Mews’ claims — John’s absurd belief, for instance, that unattractive criminals are less likely to reoffend if their faces are made more beautiful. But in the weeks that followed, I experienced a swift, overwhelming change in vision — the kind the Mews’ patients and viewers described undergoing. Suddenly, all around me, people with tiny jaws appeared, their chins merging with their necks, their lips hanging open unconsciously as they read a book in a cafe or stared out the window on the bus. Long faces, tired eyes, crooked smiles. It began to feel as if the Mews might be right on this single but essential point, if on nothing else.

Orthodontists’ unwillingness to engage with this claim — that industrialised life was shifting our teeth and reshaping our jaws — showed, at the very least, a confounding lack of curiosity about the causes of the problem they were looking at. If the Mews were right, then the implications were sweeping: Orthodontists had made billions treating patients for a problem that could have been prevented all along.

But I wasn’t sure if I trusted my eyes or not, and I wanted a second opinion. I decided to make a visit of my own. On a Friday in August, I met with an anthropologist named Janet Monge in a ground-floor classroom at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia, which has one of the world’s largest and most geographically diverse collections of ancient skulls, housed at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Morton specimens sat in cases all around, peering out at us with enormous, empty sockets and gleaming teeth. In a plastic container, Monge had placed skulls from the Middle East, West Africa, Eastern Europe and beyond. When I asked her if she’d ever seen an ancient specimen with crooked teeth, she didn’t hesitate: “No, not one. Ever.” Most of the skulls in the Penn collection date from a 40,000-year period starting late in the Stone Age and ending around 300 years ago, yet “they all have an edge-to-edge bite,” “robust” jaws and “perfect” occlusion, Monge said.

But then, in specimens from people who lived two centuries ago or less, Monge noted a striking change: The edge-to-edge bite completely disappears, and malocclusion suddenly runs rampant. She pointed to a skull on a nearby shelf — that of a woman who lived in 19th-century North America. Unlike the ancient skulls, this postindustrial woman’s maxilla was crinkled and small; the teeth that remained sat crammed together. “I always told my students, ‘Something happened 200 years ago and nobody has an edge-to-edge bite anymore — and I have no freaking idea why,’” Monge said.

She took the skull of a preindustrial Siberian man out of her container and clicked the mandible into place. The bone was thick; the teeth met so neatly that they appeared pulled from an Invisalign ad. Monge laughed, her open mouth revealing a pair of missing molars. She cradled the skull in her hand. “Isn’t that just perfect?”

[link url="https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/20/magazine/teeth-mewing-incels.html?"]Full New York Times Magazine article[/link]