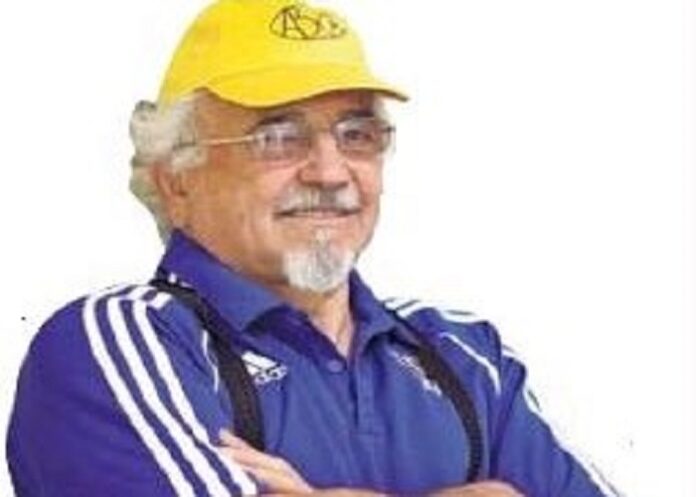

Family, friends and colleagues are mourning the passing of Costa Gazidis (90), community doctor, political prisoner, Aids campaigner, fiercely independent anti-racist and socialist who found his political home in the Pan Africanist Congress.

He died in London last week after a long illness. He was 90. He had travelled from his Cape Town home in 2018 to visit family and friends in England, but fell ill and never fully recovered.

Known throughout many areas of the Eastern Cape as “Doctor Gazi”, he spent 22 years in exile before returning to South Africa in 1991 where he taught at the University of Transkei.

He was then appointed as the public health specialist at Cecilia Makiwane Hospital in Mdantsane, a position he held as the HIV/Aids epidemic struck amid official denials that it existed.

Gazidis responded by campaigning for the use of antiretroviral drugs that could, at the very least, prevent the spread of the virus to unborn children. When the Health Department refused to respond, he financed the drugs out of his own pocket and provided them to pregnant, HIV-positive women.

Daily Maverick reports that these actions saw him sacked from his post and charged with insubordination and a slew of alleged regulatory breaches. He fought back, was vindicated by the courts and the regulatory breaches were dropped.

Isolated by the official Health Department, he was elected as a Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) councillor in East London. One of the few “white” members of the party, the PAC had been his political home since he broke from the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the ANC.

That break came after he, his first wife, Dorothea, and their two children went into exile in 1968. He had been issued with a banning order in 1966 and effectively blacklisted as a doctor in South Africa.

With hundreds of other activists he had been detained and interrogated in July 1964 under the “90-day law”. Detainees, like himself, who were found to have been members of the SACP, were sentenced to various prison terms and, on release, were severely restricted. Exile seemed the only choice.

The family arrived in England at the time Soviet troops were crushing the popular “Prague Spring” uprising in Czechoslovakia that demanded “socialism with a human face”. It was an event that saw Gazidis leave the Soviet-supporting SACP and the ANC.

As he would later explain, that decision also stemmed from disagreement with the “multi-racial” policy of the ANC that was in line with the SACP concept of “nationalities”. What this meant was that the ANC alliance was organised on racial lines into “African”, “white”, “coloured” and “Indian” congresses.

He had also come across the work of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, the jailed leader of the PAC. For Gazi this was summed up by the slogan, “There is only one race – the human race”.

So it was that an exiled public health specialist in the English Midlands, who claimed never to have been an ideologue, joined the PAC, which was categorised by most of the media as “anti-white”. His decision then, he once admitted, was very similar to how and why he had joined the SACP.

At university he had read the then illegal Communist Manifesto of 1848. It revealed to him the sort of democratic and egalitarian world he wanted for the future and he became a ready recruit to the SACP. But when he felt principles were no longer being adhered to, he left and sought a political home more amenable to what he thought was right.

It was a belief in humanity and a future world of peace and plenty that seemed to drive this son of Anatolian Greek immigrants.

He will be sorely missed, not only by his six children, his stepson and third wife, Janet, but but also by a multitude of friends, comrades, colleagues and former patients.