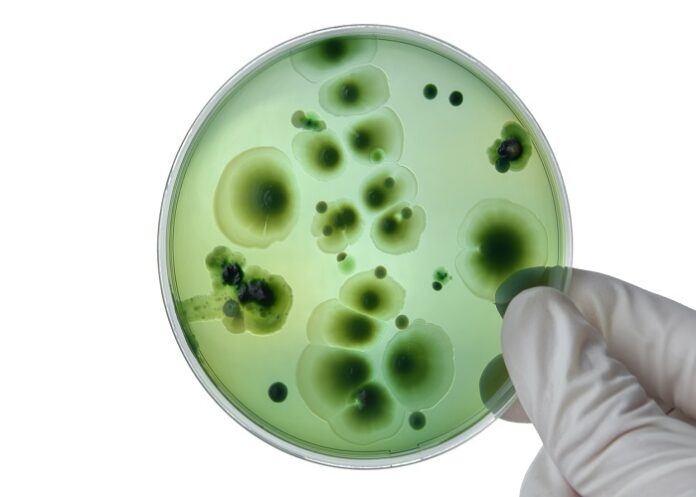

A newly named fungal species has global scientists worried about its stubborn resistance to usually effective first-line drugs, the fact that it can be frequently misidentified, and its ability to spread.

The concern is such that in collaboration with the International League of Dermatological Societies, the American Society of Dermatology has opened a registry in the hopes of gathering global information about the fungus, T indotineae.

In late 2022, US dermatologist Avrom Caplan, MD, started treating a patient who had made multiple emergency department visits for a scaly rash, and who had been diagnosed, previously by Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital, with ringworm – also known as tinea or dermatophytosis.

The rash, however, had not responded to three rounds of topical steroids and antifungals, and Caplan, an assistant professor at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City, saw immediately that the case was unusual.

There were not just a few lesions, but many, covering the patient’s thighs and buttocks: maddeningly itchy discs that were striated as though the infection had pulsed as it expanded on the skin, reports JAMA Network.

“If you see that much tinea, one of the first things you think as a dermatologist is, ‘Oh, I wonder if this person is immunosuppressed’,” Caplan said. This patient, however, wasn’t.

Caplan prescribed four weeks of oral terbinafine, a common first-line drug that is typically highly effective. It made no difference.

His next try was a month of another oral antifungal, griseofulvin. The plaques shrank considerably but did not vanish. Meanwhile, Caplan extracted the patient’s story.

The problem had started while visiting Bangladesh. Several relatives there had similar rashes, and the patient and family all treated the eruptions with antifungal and steroid combination creams available over the counter. After the patient came back to the US, the rash recurred.

The combination of travel-acquired infection, family contagiousness, and failure to respond to recommended drugs made Caplan uneasy. He asked the Bellevue dermatology residents if they had seen any other cases, and they had: a patient who had the same crusty, ring-shaped patches not just on the thighs and buttocks but extending up the abdomen and neck.

The residents had prescribed oral terbinafine without success. It took four weeks of itraconazole, a less-preferred second-line antifungal in a different drug class, to clear the rash this time.

In a disturbing extra detail, this patient had not travelled abroad recently, which meant the stubborn, spreading rash must have been contracted locally.

Caplan contacted both the New York State Department of Health and the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

At the state health department, technicians in the public health laboratory identified the cause of both cases as a newly named fungal species, Trichophyton indotineae.

Caplan and co-authors described the first cases in the US in the CDC’s MMWR last year.

At the CDC, medical mycologists and epidemiologists worried they were hearing a warning bell. For several years, they had been tracking the advance of highly transmissible terbinafine-resistant dermatophytosis across the globe, talking to international colleagues who observed the superficial fungal infection in patients in South Asia starting in the mid-2010s, then in Canada, East and Southeast Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

Two cases were also reported in South Africa in January this year, in KwaZulu-Natal, and confirmed by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases.

In all of those locations, the accounts of T indotineae were the same. Patients exhibited persistent, expanding, intensely itchy lesions that spread to parts of their bodies where ringworm didn’t usually manifest, including the face. The itch deprived people of sleep.

The scaly reddened plaques felt stigmatising, making the patients want to stay home and hide. And the symptoms were unaffected by even-longer-than-usual courses of first-line drugs.

As the CDC’s medical mycologists assessed the new organism, they realised that its diminished drug response would create a public health challenge.

“The estimated lifetime prevalence of ringworm is one in four people,” said epidemiologist Jeremy Gold, MD, MS, a medical officer in the agency’s mycotic diseases branch who co-authored the MMWR report. “This isn’t necessarily something that will kill people, but it really has the potential to spread widely and affect lots of lives.”

A cautionary tale

Clinicians in India have been dealing with a T indotineae epidemic for almost a decade now, with several confirming how disruptive the organism – previously named T mentagrophytes genotype VIII, or TMVIII – has become.

“Around 2014, we started seeing atypical, widespread manifestations of non-responsive dermatophytosis,” said Ramesh Bhat, MBBS, MD, a professor of dermatology at Father Muller Medical College in Mangalore, India.

A multi-centre study by Bhat and colleagues from 2014 to 2018 found that a high percentage of nearly 500 fungal isolates from skin infections had diminished susceptibility to several antifungals, including 11% that had some resistance to terbinafine. “And over the years, that has increased,” Bhat said.

In the mid-2010s, the rise of resistant ringworm across the subcontinent led Indian researchers to form an informal brain trust, through which they shared accounts of how these cases differed from the norm.

“We used to have patients in summers and the rainy season, when there was high heat and humidity, but we began to have the same prevalence in winters,” said Archana Singal, MD, director professor and head of dermatology and sexually transmitted disease at the University College of Medical Sciences in New Delhi and editor in chief of the Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprology.

The researchers wondered what might be driving this.

“When we looked for something in the background, what was very obvious was lots of misuse of topical corticosteroid, antifungal, antibacterial combination creams,” said Manjunath Shenoy, MBBS, MD, a professor and head of dermatology at Yenepoya Medical College in Mangalore.

In a country where much of the population lives far from specialists, “it’s very common that someone would not be treated by a dermatologist but would buy these”, he said.

At about the time the fungal infection was burgeoning, the Indian Government took regulatory action against over-the-counter combination creams, like the one Caplan’s patient had used. However, some of the products were reformulated to escape the ban and returned to market still containing powerful steroids.

In conversations with patients, the researchers began to understand how tinea had gained drug resistance. “These creams are used not only very widely but also erratically,” said Shyam Verma, MBBS, PhD, a dermatologist in private practice in Gujarat.

“The potent steroid quells the itching, so people use it for five, six days, and then stop. It leads to a pool of patients who are not completely cured, who are then a source of infection to everyone else.”

Shenoy highlighted a further complication: people also buy the same steroidal creams for skin lightening, unknowingly making themselves vulnerable to fungal infection by inducing localised immune suppression.

Defining the emerging epidemic has depended on case reports and surveys on recalcitrant dermatophytosis. In 2016, physicians at a hospital in Chandigarh reported that treatment-resistant dermatophytosis accounted for as many as 10% of all new cases at their clinic.

Shenoy and a team of co-authors identified treatment resistance in about 28% of more than 7 000 patients with dermatophytosis in a study at 13 medical centres in India between 2017 and 2018.

And in 2021, 52% of 459 dermatologists who responded to a survey about treating dermatophytosis reported that they encountered treatment failure from antifungal resistance.

Meanwhile, drug-resistant tinea has expanded globally, including recently to Australia and Latin America. (A screening of genetic sequence records also identified it as having been present in several countries before the epidemic in India was recognised in the mid-2010s.)

A database search at the University of Texas Health Science Centre at San Antonio, one of the premier fungal reference laboratories in the US, revealed a resistant isolate from North America dating to 2017, well before Caplan had encountered it in New York.

This year, he and co-authors from the New York State reference laboratory and five other medical centres published a case series in JAMA Dermatology of 11 patients who were treated for T indotineae in New York City between 2022 and 2023, most after travel to Bangladesh.

It included the two patients in his initial case report, both of whose terbinafine-resistant rashes ultimately resolved with different antifungals.

Gathering intel

At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Boni Elewski, MD, a professor and chair of dermatology, has seen three patients with probable treatment-resistant T indotineae since 2020 and has been asked to consult on other cases.

Repeatedly, she has run into a lack of appropriate antifungals to continue therapy after first-line drugs failed, and next-line options were contraindicated or would violate antifungal stewardship guidelines.

“The problem is, we have only three drugs that have been out roughly since 1990,” she said, naming terbinafine, itraconazole and fluconazole. Newer antifungal drugs like voriconazole and posaconazole are generally reserved for systemic infection, she explained. “They have significant side effects. They’re expensive. They’re not for routine use.”

The lack of a robust antifungal arsenal and comprehensive fungal-infection surveillance are not new problems. In the past, the CDC has named both as factors in the unanticipated spread of invasive fungal infections like Candida auris.

Recognising that drug-resistant tinea had been identified in multiple countries and was often linked to travel, and that the clinicians most likely to encounter it when it arrived would not be medical mycologists, but primary care physicians and dermatologists, the agency began drafting educational campaigns in collaboration with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD).

This July, the AAD opened an Emerging Diseases Resource Centre on its website, including information pages on diagnosing and treating T indotineae. A key challenge is that standard fungal culture misidentifies it as a common, closely related species; the online resource lists contacts for the few laboratories capable of distinguishing T indotineae from other similar strains using genomic sequencing.

The pages also offer access to a new case registry for resistant dermatophytosis, an extension of one that was initially created for dermatologic manifestations of Covid-19 and then expanded to help track mpox cases.

The registry is being conducted in collaboration with the International League of Dermatological Societies in the hopes of gathering global information.

The objective is to collect data on presentations of resistant dermatophytosis while also serving as an early-warning system, said Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, the registry’s principal investigator and director of global health dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“I think of the registry as a great place for hypothesis generation and a great place to rapidly collect data from many countries in a systematic way,” she said. “Our goal is to feed back to people who are on the front line: these are the risk factors you should be looking for, and these are the clinical patterns you should be looking for. And doing that on a global scale.”

The registry may be arriving just in time. Dermatologists are noticing that other fungal dermatophyte species are behaving in anomalous ways. In 2014, clinicians in Europe began observing severe infections with a related species called T mentagrophytes genotype VII (TMVII) on patients’ genitals, an uncommon location.

The first reported cases involving a closely related species occurred among men and women who visited clinics in Zurich, Switzerland, after having sex in Southeast Asia with local sex workers or other tourists; the patients required two to 10 weeks of oral terbinafine or itraconazole treatment.

Several also needed systemic prednisone to quell inflammation, and two were in so much pain they were hospitalised.

Other European case reports of TMVII involving sexual contact or genital grooming were described in 2019 and 2021, but what has dermatologists especially concerned is a case series researchers in Paris published last year in the CDC’s journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Their 13 patients were almost all men who exclusively had sex with men; many of the patients had travelled. This raised the possibility that the fungal infection could spread among international social-sexual networks in the way that the mpox virus did in 2022.

It took from three weeks to four months of systemic treatment, with terbinafine, itraconazole, or voriconazole, for some of the infections to resolve.

Caplan has seen a patient with confirmed TMVII infection in New York. The case, described in JAMA Dermatology this June, is a possible indication of more to come.

“TMVII thus far seems to respond to terbinafine,” he said. “But one of my worries is, what happens if TMVII meets TMVIII, T indotineae, and picks up its resistance patterns? What is the potential that that is going to spread?”

For its part, the AAD’s new registry is designed to prompt clinicians to supply details of dermatophyte infections beyond T indotineae that exhibit unusual treatment resistance and heightened transmissibility. The site recently opened for submissions, and its investigators are waiting anxiously to see what might turn up.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Silent epidemic of deadly fungal infections in Africa

WHO launches first list of most risky fungal pathogens

UFS welcomes WHO’s recognition of fungal infections threat