Twenty years after he was convicted, a new BBC documentary examines why it took so long to catch Britain's most prolific serial killer, Dr Harold Shipman.

By the account of all his patients – all, that is to say, who survived – Harold Shipman was the perfect family doctor; an old-fashioned GP in the best possible sense of the term, reports The Daily Telegraph.

In an age when most doctors were tied to their surgeries, Shipman was always ready to visit his patients at home – particularly elderly, vulnerable women. He was ready to listen to their complaints, no matter how minor, was solicitous, caring and kind – ‘a patient’s dream’, as one would put it – right up to the moment that he murdered them.

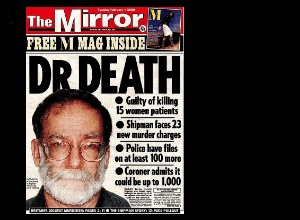

By the time he murdered Joseph Bardsley, Shipman had already killed 13 people – and he would go on to kill many more. In January 2000 he was found guilty of the murder of 15 women, all of whom had been his trusting patients. But that number was merely the tip of a gruesome iceberg. Shipman is believed to have murdered more than 250 people – and there are possibly more that will never be known. He committed suicide while in prison.

‘The question people always ask about Harold Shipman is, how did he get away with it?’ says Chris Wilson, writer and director of the series. ‘The received wisdom is that it was because of the deference which people had towards him because he was a doctor. That’s partly true, but I think it’s also because he chose to kill mainly elderly people, and as a society we care less about older people. It’s a case of, “Oh well, good innings, never mind.”

Colleagues who worked with Shipman over the years would remember him as arrogant, supercilious and sarcastic to anyone who sought to question or challenge him. McKeating describes an ego ‘as big as a bucket’. To his patients he was the complete opposite; kind, caring and solicitous – the very qualities that afforded him the opportunity to kill with impunity.

Wilson says that in the course of researching his series, he was told that some people in Hyde had half-jokingly referred to Shipman as ‘Dr Death’ ‘for years’. Police at one stage conducted a confidential investigation into Shipman, but no charges were brought.

At the government inquiry into Shipman’s crimes following his conviction, the chair Dame Janet Smith criticised both the investigating officer, DI David Smith, for failing to explore records of comparative death rates, and Dr Alan Banks of the West Pennine Health Authority, who examined the medical records of patients who had died under Shipman and failed to notice the unusual pattern of death. Banks, Dame Janet said, was ‘simply unable to open his mind to the possibility that Shipman might have harmed a patient’.

The Shipman Inquiry, under Dame Janet Smith, spent two years investigating a total of 618 deaths that had occurred under Shipman, concluding that he had been responsible for the murder of 215 patients, with a further 45 deaths deemed suspicious.

It was a fatal combination of deference to the medical profession, systemic failings, luck – and his own cunning – that enabled Harold Shipman to continue to kill over the decades. ‘He was able to exploit his power and status and factors that were unique to him being a doctor,’ Chris Wilson says. ‘He had access to the drugs to kill; he could sign the death certificates, avoid there being a post-mortem. He found ways to exploit the system, and at that time that system was particularly vulnerable to exploitation.’

In her concluding remarks to the first phase of the Shipman Inquiry, Dame Janet Smith pointed to the failure of systems that should have safeguarded patients, or at least detected misconduct, but also to ‘the esteem’ in which Shipman was held by his patients. This, she said, ‘ensured that very few relatives felt any real sense of disquiet about the circumstances of the victims’ deaths. Those who did harbour private suspicions felt unable to report their concerns.’

Shipman, she went on, had ‘betrayed their trust in a way and to an extent that I believe is unparalleled in history’. The Shipman Inquiry would lead to wholesale changes in medical practice to do with the supervision of GPs, an overhaul of the death certification process, changes in the coroner’s system and the monitoring of controlled drugs.

‘It was probably one of the greatest reforms in the way doctors were monitored and scrutinised there has ever been in this country,’ says Professor Aneez Esmail, a GP and academic at the University of Manchester, who was medical adviser to the inquiry.

Part of his remit was to make a thorough study of Shipman’s notes during his time in Hyde. “As things were then, he was able to practise without any oversight at all. He was lying consistently, fabricating medical records after the event to cover his tracks, and there was no way of anyone being able to pick that up. It’s all very well to have hindsight and say, ‘We should have known this or done that,’ but at that time doctors were unassailable. The sad thing was that after this people thought, can we ever trust a doctor again? That’s the tragedy. We’ve lost so much, because of that case.”

The report says a burning question that remains unanswered about Shipman is, why did he do it? In the course of the Shipman Inquiry, Esmail says they consulted numerous forensic scientists and psychiatrists in search of a theory, if not an answer. “They described it as an addiction to power,” he says. “And it was a slippery slope. When you look back to… the earliest cases, I think he was probably attempting to ease the passing of people who were terminally ill.”

“I think it was then he began to realise the power he had over people’s lives,” Esmail says. “He realised he could kill, so he did.”

[link url="https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/0/did-take-decades-catch-harold-shipman/?WT.mc_id=e_DM1255808&WT.tsrc=email&etype=Edi_FAM_New_ES_Sat&utmsource=email&utm_medium=Edi_FAM_New_ES_Sat20200613&utm_campaign=DM1255808"]Full report in The Daily Telegraph[/link]