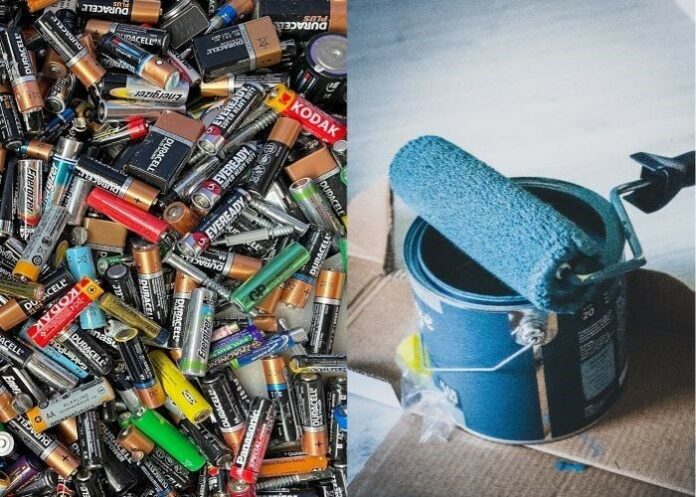

Children who are exposed to lead – found in certain paints and batteries – can face various problems later on, and while researchers found lead poisoning was widespread across major South African cities in the 2000s, and recent evidence shows a problem in certain mining and fishing towns too, just three cases were reported to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases between 2017 and 2022.

This, say experts, is because the medical fraternity thinks the threat posed by the metal is a thing of the past, writes Jesse Copelyn for Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism.

Lead poisoning has been linked to violent behaviour, declining IQs, and heart disorders, and is pervasive in several communities. Yet, says Susan Nzenze-Chinyoka, head of the NICD's notifiable medical conditions team, few cases are ever reported. Because lead poisoning is a notifiable medical condition, she said, it's a crime for health workers not to flag cases to the NICD.

Notifiable conditions are illnesses posing potential public health risks that can result in outbreaks or epidemics and therefore require government monitoring.

Lead poisoning is a category two notifiable condition, meaning it needs to be reported to the Department of Health within seven days after a doctor or laboratory has identified a case. A test has to pick up at least five micrograms of lead for every 100ml of someone’s blood before they’re considered to be poisoned. This amount is called the blood lead reference level and it signals someone has an unusual amount of lead in their blood and needs treatment.

South Africa’s problem, however, wasn’t that health workers were failing to tell the government what they were seeing, it was rather that they were missing cases of lead poisoning altogether, said Angela Mathee, the chief specialist scientist at the SA Medical Research Council’s (SAMRC) environment and health research unit.

“It seems health workers are unaware of how widespread lead poisoning is,” she said. “Part of the problem is that in the medical fraternity, there’s this belief that lead poisoning is a historical issue, and not relevant to contemporary society.”

What is lead used for?

Lead is a metal used in certain paints, batteries, bullets, and even in some homoeopathic medicines. The heavy metal is added to paint to increase its durability and prevent corrosion, but because of the dangers of lead exposure, many countries, including South Africa, have placed legal limits on how much lead can be added to paint.

However, because numerous buildings were already painted by the time South Africa introduced these laws in 2009, there were still countless homes covered with lead paint, said Mathee.

Lead has even been found to contaminate garden soil in some Johannesburg neighbourhoods (in part, because lead paint flakes and settles as dust on the ground). And cases of widespread lead poisoning in South Africa stretch far beyond Johannesburg.

In 2007, for instance, researchers found nearly three-quarters of kids aged five to 12 in Kimberley, Cape Town and Johannesburg had lead poisoning. And in 2012, studies showed 74% of school children (six to 14) tested in the two West Coast fishing communities of Struisbaai and Elandsbaai had lead poisoning.

Researchers found people in these two towns were unaware of the health effects of lead: 80% of those surveyed did not know the toxic metal could make you sick.

As a result, many fishermen would melt down lead from old sinkers they found on the beaches to make new ones, often in their own homes while children watched. Sometimes, kids even participated.

Lead’s toxic effects are especially bad for children.

They’re curious and explore the world by putting things in their mouths, so they’re more likely to consume lead that might be in the soil or in flakes of old paint. And once the metal is in their system, more of it will be absorbed into their bones, teeth and tissues when compared to adults. This compounds the damage to their developing bodies.

One such consequence is that, in the long term, lead exposure can make people more violent: a large body of causal research shows when countries reduce the amount of lead to which children are exposed, the national crime rate goes down.

People who grow up exposed to lead at a young age also end up with lower scores on intelligence tests. The likely result is that children have a harder time succeeding in school, or earning a decent living as an adult.

What has South Africa done to fight lead poisoning?

The two biggest things the government has done to cut people’s risk of lead exposure is to ban the use of lead petrol in 2006, and to slash the legal limit for lead in paint.

Household paint containing more than 0.06% lead was outlawed in 2009, and that threshold was dropped even lower (down to 0.09%) in October 2021. The new rule now applies to all paints, including those used in industrial settings, on road signs and on billboards.

But these laws might not be effective since the government did not punish manufacturers who broke the rules, industry groups and public health experts said.

In the US, a range of measures have effectively countered the negative effects of the metal, for instance, the removal of lead paint from the homes of children diagnosed with lead poisoning.

But environmental health experts worry South Africa doesn’t have a concrete plan to roll out such projects.

The country’s plan to fight noncommunicable diseases includes a goal to establish a national lead exposure prevention team between 2022 and 2027, but the health department didn’t respond to Bhekisisa’s queries about whether this group exists or what its exact responsibilities would be.

The SAMRC, and the Departments of Health and of Forestry & Fisheries announced plans to launch education campaigns on lead in October last year alongside the environmental justice group, groundWork, but groundWork also hasn’t responded to our queries about whether such campaigns have been developed and implemented.

Tooth marks in toxic paint: How much lead are SA children exposed to?

In the mid-2000s, Matthee and her colleagues at the SAMRC were testing the paint used on children’s toys for traces of lead. She was horrified to find lots of the metal on toys inside her own home. The lead levels on her daughter’s building blocks were among the highest of all the goods the researchers tested.

And the little girl’s tooth marks on the blocks were especially worrying.

“I had been working on lead issues for nearly two decades, and it struck home that unless there are protective measures in place, none of us, no matter how much you know, can protect our children against this public health hazard,” Mathee told Environmental Health Perspectives. Her investigations would eventually inform South Africa’s 2009 paint regulations.

Have the new rules worked?

It was hard to tell, she said, because there had never been a national study to evaluate how much lead South Africans could have in their blood.

Research conducted since the regulations kicked in doesn’t inspire much hope, however, as small-scale studies continue to find South Africans have high levels of lead poisoning. Things are especially bad in older neighbourhoods such as Bertrams, a working-class suburb in Johannesburg’s inner city.

There, the average Grade 1 pupil at one primary school had blood lead levels twice as high as South Africa’s threshold for lead poisoning.

Why? Because as one of Johannesburg’s oldest suburbs, the schools and houses in Bertrams were probably covered in lead paint.

And no amount of lead exposure is safe. Even tiny amounts of the metal can result in long-term damage.

Why lead still lurks in South African soil and air

So, what can South Africa do about the toxic paint that remains plastered on buildings across the country? In wealthier countries such as the US, the answer is fairly straightforward: remove or cover it.

This often involves an expensive procedure in which professionals fully strip the paint and dispose of it in hazardous waste dumps. In other cases, cheaper (but more temporary) methods are used to seal lead paint with certain coatings or plastic.

The Biden administration announced plans to beef up these efforts in December. His government will spend roughly R88bn to remove or manage lead paint and other lead fixtures (such as pipes) in low-income households.

But in South Africa, no such plans existed, according to Rajen Naidoo, a professor of occupational and environmental health at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

“New paint products are expected to meet the new standards but old paint in homes and other buildings is not regulated.”

That there was no plan to manage old lead paint was concerning, he said.

“It presents a risk, particularly in ageing buildings and in residential homes, where you have peeling paint or old paint dust falling on to floors.”

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Lead bullets at shooting ranges a health risk, should be phased out

Open access database documents toxic agents

Prenatal BPA exposure linked to asthma in girls – Meta-analysis of 8 European birth cohorts