In an extraordinary find, the earliest known evidence of a successful surgery was discovered in the skeletal remains of a young adult who lived at least 31 000 years ago in Borneo, who survived an amputation researchers say implied “the use of unexpectedly advanced medical practice”.

The remains were discovered in the Liang Tebo cave in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, and it appears the person survived the amputation of their lower left leg just above the ankle, probably when they were a child, an estimated six to nine years before death.

Evidence was determined by the remodelled bone at the site of the amputation and the lack of evidence of infection, suggesting the use of unexpectedly advanced medical practices, reported Tim Ryan Maloney, PhD, of Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and co-authors.

The discovery predates what was considered to be the earliest evidence of surgery by tens of thousands of years, the team wrote in Nature.

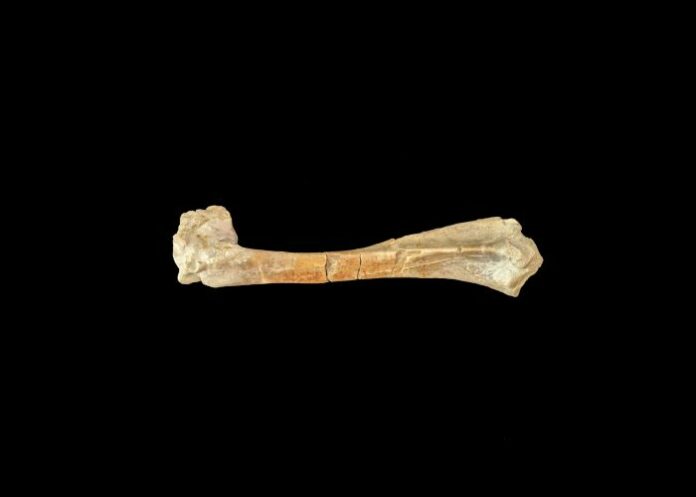

After careful excavation of the burial site where the skeleton was discovered, researchers noted the absence of the bones in the left foot and lower fibula and tibia. Those fragmented leg bones had unusual signs of “bony growth”, they said. Furthermore, lamellar bone was completely remodelled in the lower area of the fibula, suggesting the individual survived for at least six years after the initial trauma. The remodelled bone was “consistent with late-stage amputation changes”, the researchers said.

They also matched the discovery to other clinical examples of amputated bones to confirm the findings.

“In all of those cases, shock, blood loss and infection were all controlled, so the match between those records is implying that those processes were part of the surgical procedure that allowed this individual to survive, which we know that they did,” Maloney told MedPage Today.

He said the person’s survival after the procedure was also confirmed by the nature of the remodelled bone, which showed signs of the individual continuing to use the lower left leg as the bone reshaped.

“As that person lived into their adulthood, they occasionally put pressure on the remaining stump of their lower left leg as the bone continued to heal into the later stages of amputation, preserving a unique signal of pressure being put on that stump,” Maloney said.

He noted that while the team doesn’t have evidence confirming the use of antiseptic or antimicrobial practices, it was possible to infer that the people who conducted this procedure used medical practices that would allow the individual to survive such a procedure.

“Obviously, we don’t have a preserved record of that, (but) we have a comparative empirical record for most clinical cases, which makes it clear that you cannot survive the removal of your lower left leg – particularly as a child more susceptible to the severity of such an operation – without managing shock, blood loss and infection,” the researchers wrote.

They said that such medical practices might have been possible due to “the development of novel pharmaceuticals, such as antiseptics, that harnessed the medicinal properties of Borneo’s rich plant biodiversity”.

The discovery has shifted the understanding of how medical advances were introduced into human societies thousands of years earlier than previously believed, noted the author of an accompanying editorial, Charlotte Ann Roberts, PhD, of Durham University in England.

Roberts wrote that it is “astounding” that the child survived for years after the amputation, and that the discovery is important “because it provides us with a view of the implementation of care and treatment in the distant past”.

Roberts also noted that the previously oldest known surgery was thought to be in a Neolithic farmer from France, whose left forearm was surgically removed, and then partially healed roughly 7 000 years ago.

The new study, she said, “challenges the perception that provision of care was not a consideration in prehistoric times”. This fact is made evident by the fact that this individual received a deliberate burial in a cave after their death, which Roberts noted might confirm that “the care provided in life by this community continued after a person’s death”.

The researchers said they have no way of extrapolating from the discovery how frequent the procedure might have been conducted at the time. However, Maloney noted that there are several contextual clues suggesting the child lived in a society with several other known advantages, including evidence of artistic expression and advanced seafaring practices.

“We can’t say how frequent it was, but we can say it was present here 31 000 years ago, coincidentally associated with these artistic people closely related to advance maritime migrations,” Maloney said. “Every measure of social and technological complexity is essentially associated with this individual’s community and life.”

Study details

Surgical amputation of a limb 31,000 years ago in Borneo

Tim Ryan Maloney, India Ella Dilkes-Hall, Melandri Vlok, Adhi Agus Oktaviana, Pindi Setiawan, Andika Arief Drajat Priyatno, Marlon Ririmasse, I. Made Geria, Muslimin A. R. Effendy, Budi Istiawan, Falentinus Triwijaya Atmoko, Shinatria Adhityatama, Ian Moffat, Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Adam Brumm & Maxime Aubert.

Published in Nature on 7 September 2022

Abstract

The prevailing view regarding the evolution of medicine is that the emergence of settled agricultural societies around 10 000 years ago (the Neolithic Revolution) gave rise to a host of health problems that had previously been unknown among non-sedentary foraging populations, stimulating the first major innovations in prehistoric medical practices. Such changes included the development of more advanced surgical procedures, with the oldest known indication of an ‘operation’ formerly thought to have consisted of the skeletal remains of a European Neolithic farmer (found in Buthiers-Boulancourt, France) whose left forearm had been surgically removed and then partially healed. Dating to around 7 000 years ago, this accepted case of amputation would have required comprehensive knowledge of human anatomy and considerable technical skill, and has thus been viewed as the earliest evidence of a complex medical act. Here, however, we report the discovery of skeletal remains of a young individual from Borneo who had the distal third of their left lower leg surgically amputated, probably as a child, at least 31 000 years ago. The individual survived the procedure and lived for another 6–9 years, before their remains were intentionally buried in Liang Tebo cave, which is located in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, in a limestone karst area that contains some of the world’s earliest dated rock art. This unexpectedly early evidence of a successful limb amputation suggests that at least some modern human foraging groups in tropical Asia had developed sophisticated medical knowledge and skills long before the Neolithic farming transition.

Nature article – Surgical amputation of a limb 31,000 years ago in Borneo (Open access)

MedPage Today article – Earliest Evidence of Surgery Found in Stone Age Amputation (Open access)