A clinical trial of the use of adrenaline in cardiac arrests has found that its results in less than 1% more people leaving hospital alive but almost doubles the risk of severe brain damage for survivors of cardiac arrest. The PARAMEDIC2 trial is expected to change treatment protocols.

A clinical trial of the use of adrenaline in cardiac arrests has found that its results in less than 1% more people leaving hospital alive but almost doubles the risk of severe brain damage for survivors of cardiac arrest. The PARAMEDIC2 trial is expected to change treatment protocols.

The research raises important questions about the future use of adrenaline in such cases and will necessitate debate amongst healthcare professionals, patients and the public.

Each year 30,000 people sustain a cardiac arrest in the UK and less than one in ten survive. The best chance of survival comes if the cardiac arrest is recognised quickly, someone starts cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation (electric shock treatment) is applied without delay.

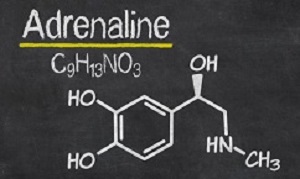

The application of adrenaline is one of the last things tried in attempts to treat cardiac arrest. It increases blood flow to the heart and increases the chance of restoring a heartbeat. However, it also reduces blood flow in very small blood vessels in the brain, which may worsen brain damage. Observational studies, involving over 500,000 patients, have reported worse long-term survival and more brain damage among survivors who were treated with adrenaline.

Despite these issues, until now, there have been no definitive studies of the effectiveness of adrenaline as a treatment for cardiac arrest. This led the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation to call for a placebo-controlled trial to establish if adrenaline was beneficial or harmful in the treatment of cardiac arrest. This Pre-hospital Assessment of the Role of Adrenaline: Measuring the Effectiveness of Drug administration In Cardiac arrest (PARAMEDIC2) trial was undertaken to determine if adrenaline is beneficial or harmful as a treatment for out of hospital cardiac arrest.

The trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research, sponsored by the University of Warwick and led by researchers in the University's Clinical Trials Units – part of Warwick Medical School. The trial ran from December 2014 through October 2017. It was conducted in 5 National Health Service Ambulance Trusts in the UK and included 8,000 patients who were in cardiac arrest. Patients were allocated randomly to be given either adrenaline or a salt-water placebo and all those involved in the trial including the ambulance crews and paramedics were unaware which of these two treatments the patient received.

The results of the trial have now been published.

Of 4,012 patients given adrenaline, 130 (3.2%) were alive at 30 days compared with 94 (2.4%) of the 3,995 patients who were given placebo. However, of the 128 patients who had been given adrenaline and who survived to hospital discharge 39 (30.1%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (18.7%) among the 91 survivors who had been given a placebo.

In this study a poor neurological outcome (severe brain damage) was defined as someone who was in a vegetative state requiring constant nursing care and attention, or unable to walk and look after their own bodily needs without assistance.

The reasons why more patients survived with adrenaline and yet had an increased chance of severe brain damage are not completely understood. One explanation is that although adrenaline increases blood flow in large blood vessels, it paradoxically impairs blood flow in very small blood vessels and may worsen brain injury after the heart has been restarted. An alternative explanation is that the brain is more sensitive than the heart to periods without blood and oxygen and although the heart can recover from such an insult, the brain is irreversibly damaged.

Professor Gavin Perkins professor of critical care medicine in Warwick Medical School at the University of Warwick (and the lead author on the paper) said: "We have found that the benefits of adrenaline are small – one extra survivor for every 125 patients treated – but the use of adrenaline almost doubles the risk of a severe brain damage amongst survivors."

"Patients may be less willing to accept burdensome treatments if the chances of recovery are small or the risk of survival with severe brain damage is high. Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage is more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest."

Professor Jerry Nolan, from the Royal United Hospital Bath (and a co-author on the paper) said: "This trial has answered one of the longest standing questions in resuscitation medicine. Taking the results in context of other studies, it highlights the critical importance of the community response to cardiac arrest. Unlike adrenaline, members of the public can make a much bigger difference to survival through learning how to recognise cardiac arrest, perform CPR and deliver an electric shock with a defibrillator. "

Dr David Nunan, senior researcher at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at the University of Oxford, said in a BBC News report that the "landmark trial" would change the way people are treated. But Professor Kevin McConway, emeritus professor of applied statistics at The Open University, said deciding whether to change the guidelines would not be an easy decision to make.

"Is it worth being treated with adrenaline if it slightly increases one's chances of surviving, even if one might only survive in a state of considerable disability? I think that's a bit difficult to say, overall."

Researchers said the urgency of cardiac arrest treatment meant it had been impossible to seek the consent of patients to take part in the trial before they had been treated, as would usually be the case. Instead, families were contacted afterwards for consent if the patient survived.

The researchers, who gained ethical approval for the study, added that a public awareness campaign about the trial had run before it had started, offering people the chance to opt out.

The Resuscitation Council, which helps write the guidelines for resuscitation used by health professionals, said it would look at the study in detail, as it expected it to inform future UK guidelines.

Abstract

Background: Concern about the use of epinephrine as a treatment for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest led the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation to call for a placebo-controlled trial to determine whether the use of epinephrine is safe and effective in such patients.

Methods: In a randomized, double-blind trial involving 8014 patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United Kingdom, paramedics at five National Health Service ambulance services administered either parenteral epinephrine (4015 patients) or saline placebo (3999 patients), along with standard care. The primary outcome was the rate of survival at 30 days. Secondary outcomes included the rate of survival until hospital discharge with a favorable neurologic outcome, as indicated by a score of 3 or less on the modified Rankin scale (which ranges from 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]).

Results: At 30 days, 130 patients (3.2%) in the epinephrine group and 94 (2.4%) in the placebo group were alive (unadjusted odds ratio for survival, 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.06 to 1.82; P=0.02). There was no evidence of a significant difference in the proportion of patients who survived until hospital discharge with a favorable neurologic outcome (87 of 4007 patients [2.2%] vs. 74 of 3994 patients [1.9%]; unadjusted odds ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.61). At the time of hospital discharge, severe neurologic impairment (a score of 4 or 5 on the modified Rankin scale) had occurred in more of the survivors in the epinephrine group than in the placebo group (39 of 126 patients [31.0%] vs. 16 of 90 patients [17.8%]).

Conclusions: In adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the use of epinephrine resulted in a significantly higher rate of 30-day survival than the use of placebo, but there was no significant between-group difference in the rate of a favorable neurologic outcome because more survivors had severe neurologic impairment in the epinephrine group.

Authors

Gavin D Perkins, Chen Ji, Charles D Deakin, Tom Quinn, Jerry P Nolan, Charlotte Scomparin, Scott Regan, John Long, Anne Slowther, Helen Pocock, John JM Black, Fionna Moore, Rachael T Fothergill, Nigel Rees, Lyndsey O’Shea, Mark Docherty, Imogen Gunson, Kyee Han, Karl Charlton, Judith Finn, Stavros Petrou, Nigel Stallard, Simon Gates, Ranjit Lall

[link url="https://warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases/using_adrenaline_in/"]University of Warwick material[/link]

[link url="https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-44859777"]BBC News report[/link]

[link url="https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1806842?query=featured_home"]New England Journal of Medicine abstract[/link]