The long-awaited low-cost benefit option (LCBO) report has finally been publicly released by the Council for Medical Schemes (CMS), but has been immediately rejected by the Health Minister as unworkable. Instead, a new plan is being proposed, which could lead to a major policy shift for medical schemes, writes MedicalBrief.

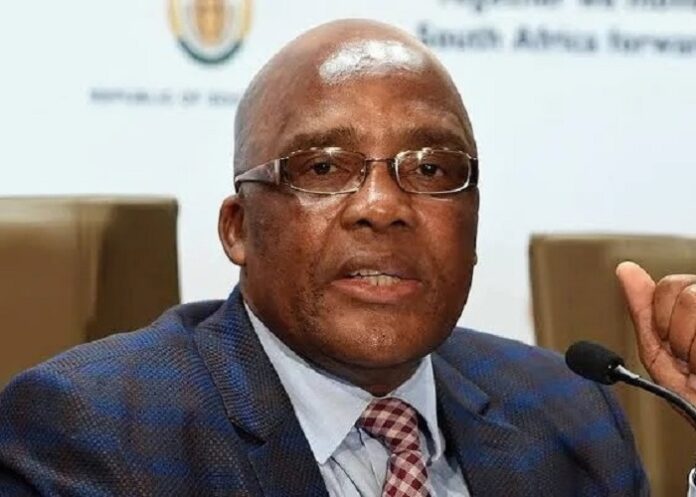

In a statement published (unusually) together with a call for comments on the report, Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi expressed his dissatisfaction with LCBO recommendations, and instead punted the implementation of the Health Market Inquiry (HMI) recommendations relating to the establishment of a basic benefit package through an amendment to the Medical Schemes Act.

This, he said, would be combined with a Multilateral Price Negotiation Forum (MPNF) which is more likely to lead to the development of a comprehensive benefit package at an affordable premium for low-income households.

To this end, the Minister of Trade, Industry & Competition published the interim block exemption for tariff determination on 14 February. The forum would be entrusted to "collectively recommend quality measurements/metrics, to the Office of Health Standards Compliance and recommend medicines formularies and treatment protocols/guidelines to the NDoH" (see story below).

But two key figures involved in the HMI say the collective tariffs negotiation plan is unfeasible (see Business Day report below).

BusinessTech reports that the CMS passed a resolution in August 2015 to adopt a framework for LCBOs offered by medical schemes but the policy stalled and was never implemented because of the lack of support from the NDoH.

This was because “they were not comprehensive and did not account for national coverage priorities like HIV and other diseases”, the CMS said at the time.

The department’s position has not changed.

The CMS started its work on a new proposal and report on LCBOs in 2020 and finally submitted its report to the Health Department last year.

Meanwhile, LCBOs have been subject to several court battles from industry bodies trying to force the government to take action.

Most recently, the Board of Healthcare Funders (BHF) approached the Gauteng High Court (Pretoria) to compel the CMS to allow the rollout of LCBOs.

The CMS and department have been accused of stifling the process to push the National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme, while rejecting exemption applications to allow schemes to continue offering these packages.

The new report lays this bare, confirming that the CMS wants the proposal shut down and current exemptions phased out.

In addition to publishing the LCBO report for public comment, Motsoaledi also gazetted his assessment of the report and the CMS’ findings.

The Minister slammed the concept of LCBOs, reflecting the conclusions reached by the CMS in the report itself, and flagged five key issues which underpinned the Department’s rejection of the option.

1. LCBOs offer less than public healthcare

The Minister said the proposed cuts to benefits under the low-cost option deliver fewer services than available at public hospitals – but private medical aids are still happy to charge for them.

He said it makes no sense why a low-income earner, the target market for these products, would pay more, or anything, for less.

“Additionally, employers are likely to be called on to contribute towards an LCBO package that is inferior in benefits and more expensive than the same service offered by the public healthcare system,” he said.

2. Not medical aid schemes

Motsoaledi said the proposals for LCBOs have not been accompanied by any research linked to the population at which they are apparently aimed.

The products are presented as “medical scheme-like products”, and only when clients attempt to access the benefits do they discover their options are extremely limited, he added.

The CMS made the clear distinction that LCBOs are primary healthcare insurance products, not medical aid schemes, and said they were likely to pull funding away from the schemes and do damage to them over time.

3. LCBOs profit driven

The Minister said he invites any and all comments, accompanied by evidence, on why LCBOs need to be low-cost low benefit plans, rather than low-cost comprehensive plans.

He said the purported objective of the plans is for the private healthcare sector to offer a package of services at affordable rates to low-income earners. This should be comprehensive, he said.

To accomplish this, private healthcare groups would have to change their pricing models, opting for higher levels of efficiency with lower profit margins. Instead, the focus appears to be on reduced benefits and higher profits.

In the CMS report, the council flagged “primary healthcare insurers” operating outside the Medical Schemes Act but benefitting from the big names that are medical schemes.

Medical schemes are not-for-profit groups. Primary healthcare companies can drive profit, the CMS noted.

4. Vague and no detail

Motsoaledi said the LCBO proposals lack detail on what services will be offered, or the quantity of each benefit.

“This information is important for consumers so they have a clear understanding of the LCBO. Permitting this level of vagueness may lead to the development and sale of products with minimal benefits.”

5. Not aligned with the NHI

The Minister’s final criticism of the LCBO proposals is that they are not aligned with the NHI, that the NHI Act “sets out a clear pathway towards universal healthcare coverage” and there is no clarity on how the LCBO proposals align with that.

The CMS noted in its report that “medical schemes and primary health insurance products are part of the challenge” in introducing the NHI.

That being the case, allowing LCBOs to be absorbed into medical schemes would not lessen this challenge, and the CMS recommended that LCBOs be outright rejected, and that current exemptions allowing insurers to offer these plans be phased out.

“The CMS advises against the introduction of the LCBO and advocates for the gradual phase-out of currently exempted products,” it said.

But in a significant policy shift, the government has opened the door for an era of collective determination of tariffs in the sector.

To be overseen by the Department of Health, this is likely to give medical aids more bargaining power in relation to providers like drug companies and hospitals, as the National Health Insurance Act looms, reports BusinessLIVE.

Trade, Industry & Competition Minister Parks Tau has gazetted an interim block exemption for both prescribed minimum benefits (PMBs) and non-prescribed minimum benefits (non-PMBs).

The exemption, for at least three years, will allow healthcare funders to bypass sections of the Competition Act that prevent competing companies from taking co-ordinated action to fix selling prices or trading conditions or divide markets.

But it will fall under a new tariffs governing body chaired by a senior Health Department official, with up to eight additional members appointed by Health’s director-general.

Tariffs will be set by a multilateral negotiating forum (MNLF) also appointed by the department, and the tariffs governing body will establish rules for tariff determination in cases where members of the forum are unable to reach agreement.

Reservations

However, the dispensation has not been enthusiastically received by the BHF, which believes the quickest solution to more affordable private healthcare would be if the Competition Commission granted exemptions to allow schemes to collectively negotiate tariffs with willing healthcare providers.

“We have serious reservations over the DTI putting the power in the Health Department’s hands to manage the block exemption negotiation process,” it said.

“This is because to date they have actively kept private healthcare expensive and inaccessible to justify the implementation of NHI.”

The department explicitly linked the block exemption to the NHI, describing it as an interim measure that would provide a system-wide regulatory framework to facilitate multilateral tariff determination.

“The promulgation of the NHI Act signals a long-term restructuring of the sector… The Act will introduce new regulatory and funding models, but until the framework is fully operational, there remains an immediate need to address the current gaps in tariff determination,” it said.

The exemption gives the green light for collective determination of healthcare services tariffs, and of standardised diagnosis, procedure, medical device and treatment codes.

Exemption would apply to specific categories of agreements or practices related to tariffs and quality standards, and excludes day clinics, mental health institutions, drug and alcohol rehab facilities and private hospitals.

Members of the MLNF will be appointed by the accounting officer of the Department of Health and will include representatives from the government, associations representing healthcare practitioners, healthcare funders, civil society, patient and consumer rights organisations, and any other regulatory body within the sector.

It will be responsible for determining the maximum tariffs for PMBs and non-PMBs for services, with its decisions expected to be taken by consensus. If members are unable to make a determination on tariffs or deviate from the determined tariffs, the governing body is authorised to make a final determination.

The government’s proposal, however, has been panned key figures involved in the HMI, who say the plan is at odds with its recommendations.

The HMI was established by the Competition Commission to probe barriers to competition in the private healthcare sector, and published its final report in 2019.

Former HMI panellist Sharon Fonn, who is a professor of public health at Wits University, said the inquiry had emphasised its recommendations were interrelated, and implementing aspects piecemeal would not foster competition or protect the consumer.

“Controlling prices achieves little in the absence of the recommended holistic framework, which addresses the incentives of schemes to contract on cost, quality and demand,” she said. In addition to a tariff negotiating structure, the HMI recommended establishing a supply side regulator to oversee healthcare providers and an organisation to monitor the outcomes and quality of the services received by patients.

“Perhaps one of the most problematic elements is that to protect patients there needs to be some system to prevent opting out. It it is likely that providers will opt out of this system and pass on additional costs to patients,” said Fonn.

Wits governance professor Alex van den Heever, who worked closely with the HMI, said the regulations lacked the comprehensive approach recommended by the HMI.

“Controlling prices in the private health system is insufficient if you do not also address demand-related incentives,” he said. “The HMI did extensive work to show that supplier-induced demand was a problem, clearly indicating that price controls will achieve nothing in the absence of broader interventions,” he said.

The proposed structure deviated from the HMI’s recommendation that any price regulator be independent and shielded from political interference, he said, noting the official in charge would be appointed by the health department.

BHF head of research Charlton Murove questioned the exclusion of private hospitals, saying they were a major contributor to medical scheme expenditure. “We know small schemes pay multiples more than big schemes,” he said.

The BHF previously failed in its bid for an exemption to the Competition Act’s prohibition on collective bargaining. Two other organisations also sought exemptions without success; the Independent Pharmacy Association and the SA Orthopaedic Association.

SA’s biggest medical scheme administrator, Discovery Health, which is not a BHF member, said it supported the move towards multilateral tariff setting. “We believe this is a fair and balanced approach to ensure the provider market remains competitive while improving sustainability in the funder market,” Discovery Health CEO Ron Whelan said.

The Health Department said private hospitals had been excluded from the exemption in line with the HMI’s recommendations. “It was the view of the stakeholders who consulted that the hospital groups already have good negotiating power based on their size. It would merely have increased the complexity and administration of the exemption and would be unlikely to further contain prices,” spokesperson Foster Mohale said.

The government had not established a supply-side regulator for health because it did not have the resources to create a new schedule 3A public entity. It was deemed feasible to administer the multilateral negotiating forum within the existing capacity of the Council for Medical Schemes and the national Health Department, he said.

Meanwhile, the number of small medical aid schemes is expected to shrink further – and, predict experts, if the NHI scheme succeeds, it could tighten the squeeze on the industry.

South Africa has 71 medical aid schemes – 16 of which are open, such as Discovery, Medshield and Bonitas; and about 55 closed or restricted schemes, mostly employer-based, like the Government Employees Medical Scheme (GEMS). There are 9.1m medical aid members, with about half belonging to open schemes.

Thoneshan Naidoo, CEO of the Health Funders Association (HFA), said that 15 years ago, there were more than 100 medical schemes, but many have had to close down, and the association expects this trend to continue.

“We do foresee, irrespective of the NHI, further consolidation of schemes in the next few years because of existing pressures, including a lack of mandatory membership and an increasing disease burden,” he told Business Times.

Consumers are also switching to schemes offering lifestyle value-added products.

The private healthcare industry – including medical schemes, healthcare providers and hospitals – has expressed concerns about certain clauses of the NHI Act, which it fears will dismantle the industry.

In its submissions to the government on the NHI, the HFA has suggested alternative ways of attaining a more equitable healthcare system and the realisation of universal health coverage more quickly and more efficiently than the process envisioned in the NHI Act.

There are also concerns that doctors and nurses working in the private sector may leave the country due to the NHI-recommended payment model, said Naidoo, adding that the first prize would be collaborating with the government on improving the healthcare system, but his organisation was also considering legal action to challenge sections of the Act.

The other key issue is around funding for NHI, which Naidoo says may cost substantially more than current spending on healthcare. The government spends about R250bn annually on public healthcare, which is funded through taxes, while the private sector spends about R280bn, which is funded by members.

He said taxes may be increased to fund NHI.

Naidoo reiterated that while the industry was in favour of universal health coverage, it supported an NHI model where both private and public coverage co-exist. The private sector, he added, could reduce the pressure on the public healthcare system via low-cost benefit options.

“By introducing low-cost benefit options, we could increase the medical scheme coverage by about 6m people, to about 15m.”

Comments on the CMS’ report and LCBOs should be submitted electronically to LCBO@health.gov.za within three months.

BusinessTech article – Big new development for cheaper medical aid in South Africa (Open access)

BusinessLIVE – Government moves to reduce healthcare costs in seismic shift

BusinessLIVE – Medical schemes face double whammy

Business Day – Proposed collective bargaining scheme for private healthcare unfeasible, say critics

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

After protests, CMS agrees to stakeholder engagement on low cost benefit options

Medical aids turn to court in long-running battle for low cost options