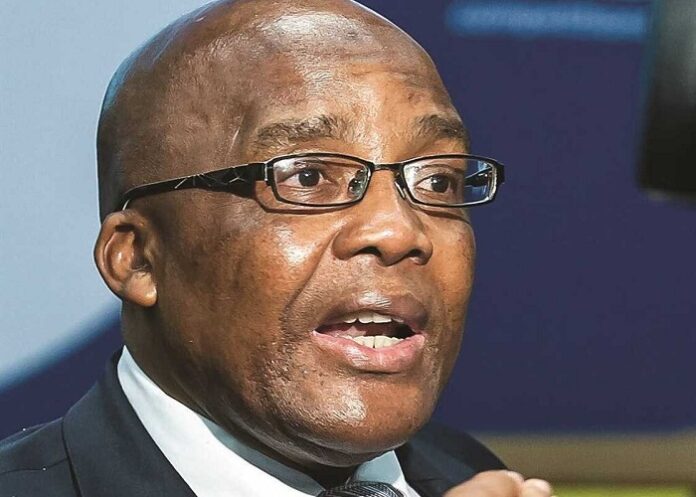

Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi has set up a committee of experts to review the compulsory community service programme for young doctors, which has caused much frustration in recent years as the number of posts available has shrunk.

Motsoaledi last week told Parliament that community service has served its purpose and should make way for creating more highly sought-after medical officer and registrar posts, reports Chris Bateman for MedicalBrief.

Foster Mohale, spokesperson for the National Department of Health (NDOH) said 11 “capable, responsible and experienced individuals,” drawn from people management in academia, governance, talent management and strategic and clinical platforms,” had agreed to serve on a Ministerial Policy Review Committee, ‘signed off’ on 1 March.

Motsoaledi would shortly announce their names, and an induction meeting would be held early in April from when they would have 12 months to make their recommendations. These would be tabled at the National Health Council. Mohale, however, said he was ‘unaware of growing calls for a policy review,’ adding that the review committee was a departmental initiative taken ‘without any undue pressure”.

In response to a question from DA MP Dr Karl le Roux, Motsoaledi said: "When you follow the history of community service, you’ll realise why we agree with you. Back then when I was still an intern it would take only one year, and it was extended to two years, and it was found that because there was an abundance of jobs many doctors were refusing to go to rural areas. It was very common to find a hospital with no doctors at all. I personally worked in such a hospital where you are alone, manning the whole hospital.

"So, community service was introduced to make it compulsory for doctors to go to rural areas. Now we fully agree with you that that is no longer the case. For this reason, the National Health Council (read the monthly Health Minister and Health MEC’ meeting), on the 29th of November last year decided that we need to appoint a group of experts to review this issue, not just to cancel it unilaterally, but to review and see whether they agree with us that the issue of community service is no longer necessary and is no longer serving its purpose.”

The stark financial pressures facing the Health Department are, however, best illustrated thus: it was unable to place 1 800 doctors who qualify for medical-officer posts, (having completed their obligatory one year’s community service.) Registrar posts have become as rare as hen’s teeth with some doctors who can afford to, working without pay to gain experience in their chosen discipline, and shortfalls in funded community service posts across provinces.

Motsoaledi told Parliament that at the end of 2024 there were just 2 128 funded community service posts; although 2 330 medical interns had completed their second and final year of internship, the last leg of training to qualify as a doctor (before completing their obligatory community service year). This meant a national shortfall of 202 community service posts.

The same issue was playing out in four other disciplines: provinces were short of community service posts for 117 environmental health practitioners, 70 pharmacists, 29 diagnostic radiographers and 18 physiotherapists. The problem was acute in environmental health, with funded community service posts for just 60% of the 295 eligible people, he added.

To mitigate the shortfall, the NDoH had engaged provincial Health Departments to convert certain posts across the nine provinces to medical community service posts,” he added.

Community service, introduced in 1998, has been plagued by poor planning, uncertainty and financial insecurity for decades, with an almost predictable annual outcry from candidates over late or inappropriate appointments at the start of every year.

In a letter published in the SA Medical Journal late last year, a group of specialists decried what they term ‘a discriminatory crisis.” They said no other healthcare worker cadre or professional group was held to such an extended period of state-controlled-practice.

Medical graduates faced a minimum of nine years (six years of undergraduate study, two years of internship and one year of community service) – before they could choose where to live or how to work.

Any scrapping of community service will require deregulation of an amendment to the Health Professions (Medical, Dental and Supplementary Health Service Professions) Act 56 of 1974 that creates the category of ‘Medical Practitioner, Community Service), after two years of internship.

The SAMJ authors added “this year (2024), the NDoH has made a unilateral decision to reduce internship posts and expand COSMO posts for 2025. This decision appears to be in response to the looming crisis of available COSMO posts”.

The consequences of ‘this incomprehensible decision’ were potentially disastrous for South Africa’s healthcare systems, they warned.

Instead of reduction, the internship programme needed strengthening, and after completion, medical officer and registrar posts should be made available.

To ensure the integrity of medical training every graduate should be given an opportunity to complete their internship without delay, and the additional posts created by scrapping the COSMO cadre made available for much needed MO and registrar posts.

Signing the letter were Drs Mark Sonderup – University of Cape Town and Groote Schuur Hospital; Shakti Pillay – UCT and Groote Schuur Hospital; Jennie Morgan – UCT and Metro Health Services, Western Cape Department of Health & Wellness; Tania Moolman-Timmermans, UCT and Groote Schuur Hospital; Marc Nortje, UCT and Groote Schuur Hospital; and Ayesha Osman– UCT and Groote Schuur Hospital.