Malaria remains one of the most devastating parasitic diseases affecting humans. In 2020 there were around 241m cases and 672 000 malaria-related deaths, a sharp increase from 2019, write Jaishree Raman and Shüné Oliver from the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) for The Conversation.

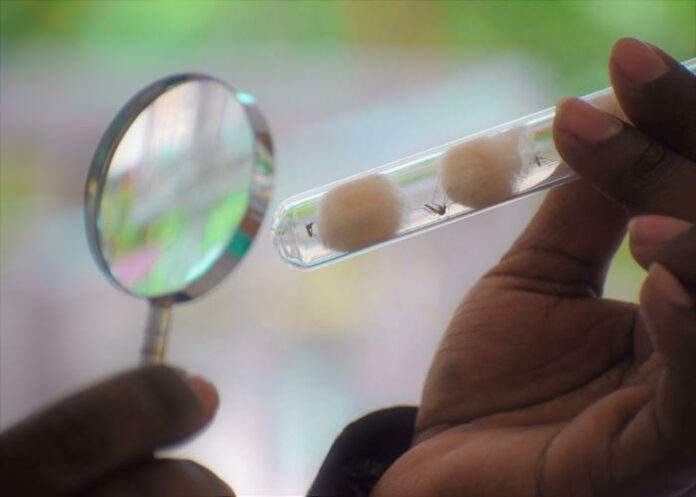

One reason it is so persistent is that the malaria parasite has a very complex life cycle. It involves many different developmental stages and multiple hosts (mosquitoes and humans).

In Africa, adding to the challenge of controlling malaria is that the continent is home to some of the most efficient malaria vectors. These include Anopheles gambiae and An. funestus. Also, the malaria parasite species Plasmodium falciparum, the dominant species in Africa, is the most lethal. It’s responsible for most malaria cases and deaths – 80% of which occur in children younger than five.

In SA, TimesLIVE reports that at least 11 people died in Gauteng from malaria between January and September.

This was revealed by MEC for Health Nomantu Nkomo-Ralehoko on Sunday which marked Southern African Development Community (SADC) Malaria Day.

According to Nkomo-Ralehoko, from January to September this year, Gauteng recorded 1 103 cases of malaria.

“Most malaria cases recorded in the province are from Mozambique followed by Malawi, Zimbabwe and Ethiopia. For every person who dies, it is one death too many, so we are working with multiple stakeholders including the tourism and transport sectors to fight this disease,” Nkomo-Ralehoko said.

She urged those who have recently travelled to and from malaria-endemic areas to seek medical treatment if they experience symptoms which include fever, chills, headache and other flu-like symptoms.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) acknowledged the challenges facing African countries when it excluded Africa from its first Global Malaria Eradication Campaign, which ran from 1955 until 1969, the writers say in The Conversation.

Since then, there have been many advances in malaria control. These include long-lasting insecticide treated nets, malaria rapid diagnostic tests and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) for malaria treatment.

But malaria elimination is still a challenge. Only two African countries, Algeria and Morocco, have been certified malaria-free by the WHO.

There are many reasons for the elimination targets remaining out of reach. Below, we highlight four: poverty, human movement, resistance and climate change.

Poverty

The limited progress towards malaria elimination is not surprising considering that some of the most malaria-burdened countries in Africa are also some of the poorest in the world.

Malaria is both a cause and a consequence of poverty. The disease will therefore remain a significant problem in Africa, if more is not done to improve the socio-economic status of malaria-affected communities. Eliminating poverty to improve the health and well-being of all are part of both the millennium and sustainable development goals. This should be a priority for governments of malaria-endemic countries.

Mobility

Africa has one of the fastest growing populations, with a high level of mobility. Marginalised and vulnerable populations are some of most mobile groups within Africa, travelling vast distances across countries with varying malaria transmission intensities.

Human mobility is strongly associated with the global spread of infectious diseases, as demonstrated by the recent COVID-19, Ebola and monkeypox outbreaks. This presents a challenge to Africa’s malaria elimination aspirations.

Malaria parasites and mosquitoes do not respect borders, so malaria services must expand to mobile and marginalised populations. Universal access to effective malaria diagnostics and treatment will reduce the malaria burden by decreasing onward transmission.

Resistance

One of the biggest threats to eliminating and eradicating malaria is the emergence and spread of insecticide, diagnostic and drug resistance.

Both the malaria vectors and parasites have proved to be very adaptable. They have rapidly developed mechanisms to survive and multiply in the presence of insecticides and antimalarial drugs, respectively.

Insecticide resistance is widespread across Africa. It reduces the efficacy of strategies based on suppressing vectors, such as long-lasting insecticide treated nets and indoor residual spraying.

To extend the effective lifespan of the available insecticides, the WHO has provided new guidance in its handbook for integrated vector management. The handbook highlights the importance of routine entomological surveillance to determine the type of vectors present, changes in vector behaviour and the insecticide susceptibility status of the vector. All of this information can guide effective vector suppression if available in good time.

Having the correct diagnostic method and treatment in place also hinges on having a robust surveillance system. The system must be capable of generating efficacy data in near real-time to allow for prompt evidence-based decision-making. The need for this type of routine surveillance has become even more urgent as African malaria parasites have developed mutations allowing them to evade detection by the continent’s most widely used rapid diagnostic tests. These undetected cases will go untreated, potentially sustaining onward transmission, resulting in major increases in malaria cases, severe disease, and potentially death.

Besides becoming invisible to rapid diagnostic tests, P. falciparum parasites in many central and west African countries have become resistant to artemisinins. This is a component of the most widely used antimalarials in Africa, ACTs. The spread of artemisinin-resistant parasites will potentially raise case numbers and deaths, repeating the devastating trend observed when drug-resistant parasites previously emerged.

The loss of ACTs would severely curtail elimination efforts as there are no novel WHO-approved antimalarials currently available.

Efforts are needed to prevent the spread of artemisinin-resistant parasites through strong surveillance and containment responses.

Climate change

The impact of climate change is complex, but there are suggestions that more places will become malaria risk areas. Mosquitoes will now be able to survive and transmit malaria in these warmer areas. This, in turn, will increase malaria cases, severe illness and deaths in the non-immune communities.

Positive developments

Despite of these challenges, there is some light at the end of tunnel.

After years of research there are two new malaria vaccines. The first, Mosquirix, has been prequalified for use by the WHO. The second, R21/Matrix M, has shown promising results in phase 2 clinical trials.

There are new long-lasting insecticide treated nets and insecticide formulations for vector control. There are also novel strategies for parasite suppression.

Adding these tools to the elimination toolbox will assist Africa get closer to malaria elimination.

* Jaishree Raman is principal medical scientist and head of Laboratory for Antimalarial Resistance Monitoring and Malaria Operational Research, National Institute for Communicable Diseases; Shüné Oliver is a medical scientist, National Institute for Communicable Diseases.

Handbook for malaria

See more from MedicalBrief archive

International partnership to combat drug resistant malaria in Africa

Eradicating malaria in southern Africa requires collaborative effort

World-first malaria vaccine to be rolled out in African countries