While cholesterol-lowering statins are commonly used worldwide, researcher Paula Byrne of the RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences in Dublin, Ireland, writing in The Conversation, says her and colleagues’ findings of a meta-analysis found that the absolute risk reduction from taking statins was modest compared with the relative risk reduction.

She writes:

Cholesterol-lowering statins are one of the worldʼs most commonly used medicines. They were first approved for people with a high risk of cardiovascular disease in 1987. By 2020, global sales were estimated to have approached US$1 trillion.

However, there has been ongoing debate about whether or not they are over-prescribed. Does everyone who takes them really benefit from them? To find out, my colleagues and I found 21 relevant clinical trials and analysed the combined data (over 140,000 participants) in what is known as a meta-analysis.

We asked two questions: is it best to lower LDL cholesterol (sometimes known as “bad” cholesterol) as much as possible to reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke or premature death? And how do the benefits of statins compare when it comes to reducing the risk of these events?

In answer to the first question, we found a surprisingly weak and inconsistent relationship between the degree of reduction in LDL cholesterol from taking statins and a personʼs chance of having a heart attack or stroke, or dying during the trial period. In some trials, reductions in LDL cholesterol were associated with significant reductions in the risk of dying, but in others, reductions in LDL cholesterol did not reduce this risk.

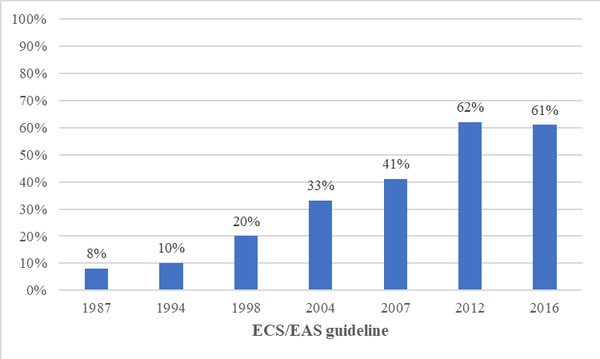

This is an important finding because clinical guidelines have expanded the proportion of people eligible for statins as “ideal” LDL cholesterol levels were incrementally lowered. For example, one study estimated a 600% increase in eligibility for statins between 1987 and 2016.

The proportion of people in Europe eligible for statins:

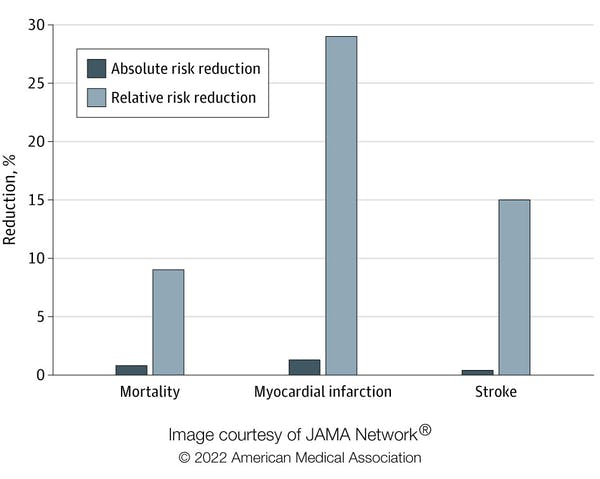

Regarding the second question, we looked at two types of risk reduction: relative risk reduction and absolute risk reduction. Imagine your chance of dying from a certain condition prematurely is 0.2%, and thereʼs a drug that reduces your chance of dying to 0.1%. In relative terms (relative risk reduction), your chance of dying has been halved, or reduced by 50%. But in absolute terms (absolute risk reduction), your chance of dying has only gone down by 0.1%.

Although there is a 50% relative risk reduction, is it a meaningful difference? Would it be worthwhile changing to this drug, particularly if there are side-effects associated with it? Absolute risk reduction presents a clearer picture and makes it easier for people to make informed decisions.

In our study, published in Jama Internal Medicine, we found that the absolute risk reduction from taking statins was modest compared with the relative risk reduction. The relative risk reduction for those taking statins compared with those who did not was 9% for deaths, 29% for heart attacks and 14% for strokes. Yet the absolute risk reduction of dying, having a heart attack or stroke was 0.8%, 1.3% and 0.4% respectively.

Absolute risk reduction compared with relative risk reduction.

A further consideration is that trials report average outcomes across all included participants rather than for an individual. Clearly, peopleʼs individual risk of disease varies depending on lifestyle and other factors. The baseline risk of cardiovascular disease can be estimated using an online calculator, such as QRisk, which takes a range of factors into account, such as weight, smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol and age.

The likelihood of a person developing cardiovascular disease in the next 10 years is expressed as a percentage. For example, consider an overweight 65-year-old man who smokes, has high blood pressure and total cholesterol. He may be at high risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with a 45-year-old, non-smoking woman with slightly raised cholesterol and blood pressure and no other risk factors. If a doctor were to assess their risk of dying in the next 10 years, the estimated risk for the man might be 38%, for example, whereas the womanʼs risk might be only 1.4%.

Now consider the impact of taking statins for both. According to the study, statins would reduce the relative risk of dying by 9%. In absolute terms, the man would reduce his risk from 38% to 34.6%, and the woman from 1.4% to 1.3%.

Patients and their doctors need to consider whether they think these risk reductions are worthwhile in a trade-off between potential benefits and harms, including the inconvenience of taking a daily medicine, possibly for life. This is particularly salient for low-risk people for whom the benefits are marginal. However, people perceive risk differently based on their own experience and preferences, and what might look like a “good deal” to some may be seen as of little value to others.

Our study highlights that patients and doctors need to be supported to make decisions about treatments using evidence from all available studies and presented in a format that helps them understand potential benefits. Both patients and their doctors need to understand the true impact of medicines, to make informed decisions. Relying on relative risk, which is numerically more impressive, instead of absolute, may lead both doctors and patients to overestimate the benefits of interventions.

For example, one study found that doctors rated a treatment as more effective and were more likely to prescribe it when the benefits were presented as relative rather than as absolute risk reductions. Another survey found that most respondents would agree to be screened for cancer if presented with relative risk reductions, whereas just over half of them would, if presented with absolute risk reductions.

If you have been prescribed statins, donʼt stop taking your medication without first consulting your doctor. Your risk profile might mean that they could benefit you. But if youʼd like to reassess taking this drug, ask your doctor to explain your absolute risk reduction and then make a collaborative decision.

Study details

Evaluating the Association Between Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Reduction and Relative and Absolute Effects of Statin Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Paula Byrne, Maryanne Demasi, Mark Jones, Susan Smith, Kirsty O’Brien, Robert DuBroff.

Published in JAMA Internal Medicine on 14 March 2022

Key Points

Question What is the association between statin-induced reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and the absolute and relative reductions in individual clinical outcomes, such as all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, or stroke?

Findings In this meta-analysis of 21 randomised clinical trials in primary and secondary prevention that examined the efficacy of statins in reducing total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes, there was significant heterogeneity but also reductions in the absolute risk of 0.8% for all-cause mortality, 1.3% for myocardial infarction, and 0.4% for stroke in those randomised to treatment with statins compared with control, with relative risk reductions of 9%, 29%, and 14%, respectively. A meta-regression was inconclusive regarding the association between the magnitude of statin-induced LDL-C reduction and all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, or stroke.

Meaning The study results suggest that the absolute benefits of statins are modest, may not be strongly mediated through the degree of LDL-C reduction, and should be communicated to patients as part of informed clinical decision-making as well as to inform clinical guidelines and policy.

Abstract

Importance

The association between statin-induced reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and the absolute risk reduction of individual, rather than composite, outcomes, such as all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, or stroke, is unclear.

Objective

To assess the association between absolute reductions in LDL-C levels with treatment with statin therapy and all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke to facilitate shared decision-making between clinicians and patients and inform clinical guidelines and policy.

Data Sources

PubMed and Embase were searched to identify eligible trials from January 1987 to June 2021.

Study Selection

Large randomised clinical trials that examined the effectiveness of statins in reducing total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes with a planned duration of 2 or more years and that reported absolute changes in LDL-C levels. Interventions were treatment with statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) vs placebo or usual care. Participants were men and women older than 18 years.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Three independent reviewers extracted data and/or assessed the methodological quality and certainty of the evidence using the risk of bias 2 tool and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation. Any differences in opinion were resolved by consensus. Meta-analyses and a meta-regression were undertaken.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome: all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes: myocardial infarction, stroke.

Findings

Twenty-one trials were included in the analysis. Meta-analyses showed reductions in the absolute risk of 0.8% (95% CI, 0.4%-1.2%) for all-cause mortality, 1.3% (95% CI, 0.9%-1.7%) for myocardial infarction, and 0.4% (95% CI, 0.2%-0.6%) for stroke in those randomised to treatment with statins, with associated relative risk reductions of 9% (95% CI, 5%-14%), 29% (95% CI, 22%-34%), and 14% (95% CI, 5%-22%) respectively. A meta-regression exploring the potential mediating association of the magnitude of statin-induced LDL-C reduction with outcomes was inconclusive.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that the absolute risk reductions of treatment with statins in terms of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke are modest compared with the relative risk reductions, and the presence of significant heterogeneity reduces the certainty of the evidence. A conclusive association between absolute reductions in LDL-C levels and individual clinical outcomes was not established, and these findings underscore the importance of discussing absolute risk reductions when making informed clinical decisions with individual patients.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Twice-yearly inclisiran injections as alternative to daily statins in NHS plan

Statins’ potential to treat MS unrelated to lowering cholesterol

Large UK study finds statins fail to lower cholesterol in over half of patients

New, cheaper pill taken with statins lowers LDL cholesterol more

Alternative to statins 'dramatically' cuts cholesterol

Statins cut peripheral artery disease mortality, even when started long after diagnosis