Fifty years ago – on 3 December 1967 – the heart of a 26-year-old road accident victim, Denise Darvall, started to beat inside the chest of a 54-year-old grocer, Louis Washkansky.

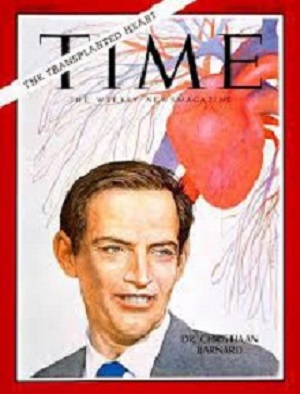

South Africa’s Chris Barnard stands out in medical history as the heart surgeon who became a global household name after transplanting that first human heart. The historic surgery captured the world’s imagination and was hailed by 20th-century historians as socially and scientifically of equal significance to the moon-landing in 1969.

Marina Joubert, a science communication researcher at Stellenbosch University writes in The Conversation that she examined aspects of this landmark surgery in two papers. The one looks at how Barnard fits into the mould of celebrity scientists across the world. The other zooms in on Barnard himself and how the media shaped perceptions of his landmark surgery.

Joubert writes: “The dramatic events that unfolded 50 years ago in Cape Town on 2nd and 3rd December, 1967 had all the makings of media gold. It was a daring world-first in medicine, performed by a largely unknown surgeon in a hospital far away from leading medical centres around the world where other surgeons were working towards the same goal. Embedded in the drama were real people set to become instantly famous and whose lives would change forever.

“Underlying it all, were moral apprehensions about whether doctors were playing God which resulted in fierce criticism of Barnard. The criticism was tempered by public fascination with the idea that one person’s heart could beat in someone else’s chest, as well as by Barnard’s explanations that the heart was nothing more than a pump.

“On top of all this, Barnard’s charisma and the increasing competition between news companies fuelled the unprecedented media interest. No other medical milestone has had such a defining effect on the relationship between medicine, media and society.

“The historic human heart transplant demonstrates the power of mass media to transform a scientist into a global icon. It highlights how public visibility offers some scientists a path to influence and power, but also illustrates that scientific celebrity comes with considerable reputational and personal risk. It reminds us that science, morals and politics have always been, and will always be, inextricably interlinked.”

Joubert writes that apartheid politics in 1960s South Africa shaped the first human heart transplant in a number of ways. Once Barnard managed to convince his superiors at Groote Schuur Hospital that he was ready to transplant a human heart, Louis Washkansky, already in the final stages of heart failure, was identified as a potential recipient. It was a race against time to find a heart donor. A suitable donor was identified, but the medical team made up of white doctors at Groote Schuur decided against using the heart of a man who under apartheid law fell into one of the categories of black people called “coloured”. They were afraid of being accused of experimenting on black people.

Joubert writes that despite the risk that Washkansky could die before the heart transplant could proceed or that another surgeon could win this race, they decided to wait for a “white heart”. Ten days later, Chris Barnard transplanted the heart of 25-year old Denise Darvall, who was left brain-dead after being hit by a speeding car.

Joubert writes: “Following this medical triumph, the South African government called on Barnard to help promote South Africa’s image around the world. A patriot at heart, he mostly obliged. But, back in South Africa, he was fiercely opposed to apartheid and later refused to allow ongoing segregation of black and white patients in his intensive care wards at Groote Schuur hospital. His anti-apartheid views led to ongoing clashes with hospital authorities and politicians.

“There were no journalists or photographers around when Chris Barnard walked out of Groote Schuur hospital on Sunday morning 3 December 1967, hours after making history. Before driving home, he called the medical superintendent of the hospital to inform him that they had performed a human-to-human heart transplant the night before.

“He told Dr Jacobus Burger: No, it wasn’t dogs. It was human beings… two human beings. Within an hour, South African Prime Minister John Vorster knew about the historic operation. The news spread like wildfire and hordes of journalists and photographers descended on Cape Town over the next few days. Chris Barnard himself famously said: ‘On Saturday, I was a surgeon in South Africa, very little known. On Monday, I was world-renowned.’

“Barnard admitted that he found it flattering to be at the centre of so much attention and he went out of his way to accommodate the media. Given his limited exposure to the media before, he had a remarkable ability to control the media agenda and steer live television interviews in his own favour. In later years, he reflected more critically on the intense media attention and its effects on medicine and society.”

Joubert notes: “The unprecedented media interest in the first human heart transplant, transformed many of the rules that governed the relationships between medicine and the media at the time. With the names and faces of recipient Washkansky and donor Darvall on front pages around the world, it shattered rules about the anonymity of organ donors and recipients, how medical procedures were reported in the media and the extent of patients’ details that were disclosed. It also fundamentally changed the way leading surgeons would be identified in and pursued by the mass media in future.

“One of the ways in which Barnard changed the way medicine was communicated was to appoint his own PR man and official photographer – something that was unheard of at the time. He allowed Don MacKenzie to take exclusive photographs of him which he could sell, after giving Barnard a fee.

“To this day, Dr Chris Barnard remains the only South African scientist who ever achieved global celebrity status. His celebrity status was boosted by his unique blend of charisma, media flair and boyish good looks. Barnard sustained it in years to come by his high-profile private life, public engagements with royalty and world leaders, as well as a series of flirtations with models and movie stars.

“He remained an iconic public figure for the rest of his life, but also continued to do pioneering work as a cardiac surgeon, including many successful surgeries on children with congenital heart disease around the world.”

Dr Ayesha Nathoo at the Centre for Medical History, University of Exeter, writes in a BBC News report that news of the first human-to-human heart transplant made headlines around the world. Journalists and film crews flooded into Groote Schuur Hospital, soon making Barnard and Washkansky household names.

Initial reports widely hailed the operation as "historic" and "successful", though Washkansky only survived a further 18 days.

Nathoo says the first heart transplant ushered in a new era of doctor and patient celebrities, post-operative press conferences andmedical PR. It became one of the most famous events of the 20th Century – as one journalist reflected, it had "everything a reporter could wish for".

Nathoo says it was an extraordinary technological feat involving the most symbolic human organ – and an intimate story of one life lost that allowed another to be saved. From his hospital ward, Washkansky's daily activities and emotions were reported in minute detail. That he sat up, spoke, smiled, and had a boiled egg for breakfast, all made front-page news. His wife and the father of the donor also featured prominently in the media coverage. They were pictured together as Mrs Washkansky wept in gratitude to Mr Darvall for agreeing to donate this precious "gift of life". After Washkansky developed pneumonia and died, their grief was publicly shared. Mr Darvall lamented the loss of his daughter for the second time, now that no part of her was "still alive".

Barnard, meanwhile, remained firmly in the limelight, the report says. Charismatic and photogenic, he appeared on magazine covers, met dignitaries and film stars, drawing crowds and photographers wherever he went.

But disquiet over heart transplantation also began and medical opinion was divided. Several other surgeons were technically ready to perform a heart transplant, and Barnard's operation prompted a flurry of international activity. In 1968, more than 100 heart transplants were performed worldwide by 47 different medical teams. Each transplant was attended by vast publicity that crossed new lines for a traditionally reticent medical profession.

Nathoo says, most of the early recipients survived only a short time – some just for hours – prompting public unease and medical critique over the visibly high mortality rates. This led to some questioning whether immunological management could keep up with the surgical ability, and if these hi-tech operations were worth the resources.

Complex ethical and legal issues arose concerning the removal of a beating heart – the traditional signifier of life and death – and whether this amounted to killing the donor patient. The incentive of doctors to save the lives of patients identified as potential donors was also called into question, especially after Barnard's second transplant, in January 1968, used the heart of a “coloured” man – the term used for mixed race in South Africa – for a white recipient in apartheid South Africa.

Nathoo says "spare-part surgery" brought hope to some and fear to others. In February 1968, a special episode of the BBC's Tomorrow's World programme – Barnard Faces His Critics – provided a key forum for probing such social and ethical implications. Involving a studio debate with Barnard alongside dozens of identifiable, eminent doctors, it also broke with professional codes of conduct regarding doctor anonymity and patient confidentiality.

As elsewhere, Britain's first heart transplant in May 1968 was also conducted and scrutinised under the media spotlight – and ultimately the publicity surrounding the controversial operations contributed to a moratorium through the 1970s.

Heart-transplant programmes restarted alongside significant advances in immunological treatments. Nathoo says they now commonly provide transformative, life-extending interventions, but the transition from Barnard's pioneering operation to today's routine surgery was far from smooth.

It was an operation that earned him acclaim, but the world's first heart transplant also provoked hate mail and outspoken criticism of Barnard, reports The Times. "We did not realise that it would take the public by storm and create such an outcry," says Dene Friedmann, a specialist nurse on the cardiovascular team, standing in the same Cape Town operating theatre where the medical feat took place. Its watery-green tiled walls, visited by schools and the public, stir many memories for her of the historic procedure. And its aftermath. "There were people who wrote quite critical letters to Professor Barnard, horrible letters calling him 'the butcher'," says Friedmann, now in her seventies.

"I have heard of human vultures, but it is the first time I have saw one with a name on it," said one letter dated just one month after the operation and sent from Illinois in the US. "You had the audacity to assume the authority of God by pretending to become the giver of life," said another from Hong Kong.

The report says the French magazine Paris Match summed up the ethical debate in a headline: "The battle of the heart. Do surgeons have the right?" But the scientific community welcomed the technical advance – the US had also been seeking the accolade – and ordinary citizens sent congratulations.

The report says at the time the heart was not considered a mere organ – it was more a symbol of deeper meaning, for some, the bringer and taker of life itself. Unlike today, there was no common legal definition of brain death and the surgical team did not want to be accused of removing a beating heart to give it to another human.

"There were still a lot of medical ethics issues. It was the first time that a heart transplant was being done… and he did not want anybody to be able to say we took out a beating heart from a patient," Friedmann says of Barnard, who died in 2001. "There was a feeling of nervousness: is this heart going to beat and take over the circulation? When it started, it was so exciting, so wonderful."

Barnard, then 45, said of the operation: "The heart lay paralysed, without any sign of life. We waited – it seemed like hours – until it slowly began to relax. Then it came like a bolt of light. "There was a sudden contraction of the atria, followed quickly by the ventricles in obedient response. Little by little it began to roll with the lovely rhythm of life."

The report says coming as it did during the apartheid years race became a consideration when selecting a donor, but only to avoid allegations of prejudice. The pioneering operation could in fact have been performed weeks earlier, when a coloured man's heart became available. "Professor Barnard had decided that the first donor had to be a white person, because of the apartheid. We did not want anyone to say 'You are taking out a black person's heart to put it in a white patient'" says Friedmann.

The report says she also squashed the rumour that persists about a black South African, Hamilton Naki, participating in the first transplant but that he was deprived by the apartheid government of any recognition. "He was very talented, but he never operated on patients," says Friedmann, who worked with Naki on many laboratory tests on dogs.

Just 18 days after the world first of the Washkansky operation, the patient died. The autopsy revealed that his lungs gave out, but not the heart, because his immune system had collapsed, resulting in pneumonia.

The report says today, a heart transplant – while still a high-risk procedure – no longer makes headlines. Around 3,500 transplants are carried out each year, of which about 2,000 are in the US. About 88% of patients survive the first year after surgery, 75% survive for five years, and 56% 10 years after the operation, according to the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Describing the ground-breaking contribution his father made to the world, his son, Christiaan Barnard Jr said in a Cape Times report: “Fifty years ago today, together with the assistance of a world-class team, right here (in Cape Town). He achieved what many believed to be impossible. And in so doing, woke up the world and united a nation, giving gravitas to the phrase ‘Proudly South African’.”

Barnard said Washkanky was more than a patient, but became a friend to his father. “The memories I have of my father’s career are not only about his medical accomplishments and successes. What made him great was his passion and compassion towards humanity, (he was) more interested in patients than procedures, more interested in their quality of life and not just the number of days we get to live it.

“And it was this joy for life that made him the man he was, made him the doctor he was and made him the father that he was. He was indeed amazing,” Barnard Jr said.

The report says he described his father as a man of extreme intellect, unquestionable drive, undeniable work ethic, charismatic, humorous and at the same time vulnerable, yet strong. “He faced some of his greatest battles professionally and personally. And he walked away from most victorious. Numerous times he was battered, bruised, but never defeated.

“Because his perseverance for the improvement and quality of life across all sectors, across all races, across all medical and political divides was resolute. I can’t wait for my young daughters to understand who their grandfather was,” Barnard Jnr said.

The head of the Christiaan Barnard department for cardiothoracic surgery at UCT, Professor Peter Zilla, said in the report that the transplant broke down the taboo barriers. “His transplant created awareness in 1967 that heart operations are possible when cardiac surgery was a very young discipline. In today’s world, it epitomises cutting-edge medicine.

“We can push the boundaries, we can do things, we can find solutions for problems that are unresolved today,” Zilla said.

Magdi Yacoub, a cardiothoracic surgeon and professor of cardiothoracic surgery at the Imperial College London, said he was recently told that a colleague had said celebrating heart transplantation was irrelevant, because it has no place in modern medicine.

“I got very upset. I have great admiration for Chris Barnard. There just is no comparison between biology – a functional heart and a mechanical device.”

In commemoration of the ground-breaking procedure, surgeons and cardiology experts from around the globe gathered at Groote Schuur Hospital to honour one of the medical world’s most respected names. News24 reports that the three-day Matters of the Heart conference kicked off with specialists giving their input for a draft "Cape Town Declaration", which will commit surgeons, academic and political heads to help the 33m people worldwide suffering from rheumatic heart disease.

The disease damages a person’s heart valves due to untreated infection of the throat with streptococcal bacteria and is said to mostly be suffered by the poor. Professor Deon Bezuidenhout, of the UCT’s cardiovascular research unit, explained that the experts attending the symposium are from both industrialised and developing nations, who will put their heads and hearts together to try and find solutions for the millions of people who are not benefiting from cardiac surgery due to access and financial issues.

While the conference looks at the history and breakthrough made by Barnard that "revolutionised medicine", it also focuses on his courage and innovation, he said. "We are looking back and tipping our hats to what happened 50 years ago, acknowledging and celebrating that anniversary. Then we are looking at what has happened since then up until now, and how we have improved cardiac surgery.

"Then we are looking forward and seeing where we are falling short, as well as what we can do further to improve the fate and lot of millions of people who still don’t have that access."

The report says the aim of the declaration was to set in motion a plan to address this, identify who would be involved, and set the first targets. "It’s obviously very difficult to eradicate a global problem, but you need to start somewhere. The idea is to sow these seeds and start with something that can then grow into something bigger."

Heather Coombes, chief operations officer of UCT start-up company Strait Access Technologies, said the symposium was the first step in a commitment from role players to "do something". "It’s not acceptable that in the US you have one cardiac centre for every 120,000 people, while in Mozambique two cardiac centres service 27m people and are situated two kilometres apart.

"It’s not right. Something needs to be done. We need to get access. We need to get these therapies into areas that need it."

And it will take co-operation and input from government, NGOs, academia, business, policy makers and healthcare workers themselves, Bezuidenhout believes.

"The conference is not about the First World coming to sort out our problems. We have to do something and they may guide and help us. It’s a commitment from all sides to acknowledge there is a problem and to commit to do something about it."

Groote Schuur Hospital's name was put on the world map for pioneering the world's human heart transplant, but, says an IoL report, since the hospital opened in 1938, it has maintained high standards of service, branding itself as one of the best teaching and public sector hospitals in the country, despite budgetary constraints.

Not only has it trained and groomed some of the best medics in the country who are sought after all over the world – including doctors, nurses and allied health personnel – but it is one of the most innovative health centres, often making medical breakthroughs.

While the hospital is known for performing the world’s first human heart surgery, the institution and its teaching arm, UCT’s faculty of health sciences, have claimed many firsts over the years.

The reports says some of the “world’s first” innovations achieved by Groote Schuur Hospital since the 1950s are:

1956: Physicist Allan Cormack develops the theoretical underpinnings of the CT (computed tomography) scanner, which led to him sharing the 1979 Nobel Prize for his work in medicine.

1965: The first rapid warming device for massive blood transfusions was developed.

1967 (December 3): The first human heart transplant by a team led by Professor Chris Barnard.

1968: The hospital’s department of surgery carried out the world’s first cross-circulation between baboon and man.

1974: The first fallopian tube transplant took place.

1974: South Africa’s first bone marrow transplant was performed.

1975: The first vascularised human fallopian tube transplant was performed.

1980s: The first (and only) sperm bank in South Africa was established in the early 1980s.

1981: Method invented for storing donor hearts by hypothermic perfusion.

1983: The first human liver transplant achieved using the heterotropic technique.

1989: A technique to locate brain tumours without invasive surgery was discovered.

2001: The department of neurosurgery introduced endovascular surgery to treat brain aneurysms, as an alternative to conventional brain surgery.

2008: The first HIV positive-to-positive kidney transplant.

2011: An ENT (ear, nose and throat) team performed ground-breaking surgery by implanting bone-anchored hearing aids (Baha) directly into the skull of two young patients.

2015: The first combined ultrasound and mammography device tested.

2016: The first open heart surgery performed through keyhole surgery.

2017: The first brain operation through the eye.

[link url="https://theconversation.com/how-an-historic-heart-transplant-created-a-celebrity-scientist-50-years-ago-88277"]The Conversation report[/link]

[link url="http://www.bbc.com/news/health-42170023"]BBC News report[/link]

[link url="https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2017-11-30-behind-the-drama-of-the-worlds-first-heart-transplant/"]The Times report[/link]

[link url="https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/news/barnards-first-heart-transplant-marks-50-years-12242614"]Cape Times report[/link]

[link url="https://m.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/experts-weigh-in-on-matters-of-the-heart-in-honour-of-chris-barnard-20171202"]News24 report[/link]

[link url="https://www.iol.co.za/lifestyle/health/watch-groote-schuur-celebrates-first-heart-transplants-50th-anniversary-12242348"]IoL report[/link]