The death of a young intern doctor at a state hospital has brought into focus the physical and mental toll on junior medical staff who have to work long, gruelling hours with little rest in understaffed public facilities, writes MedicalBrief.

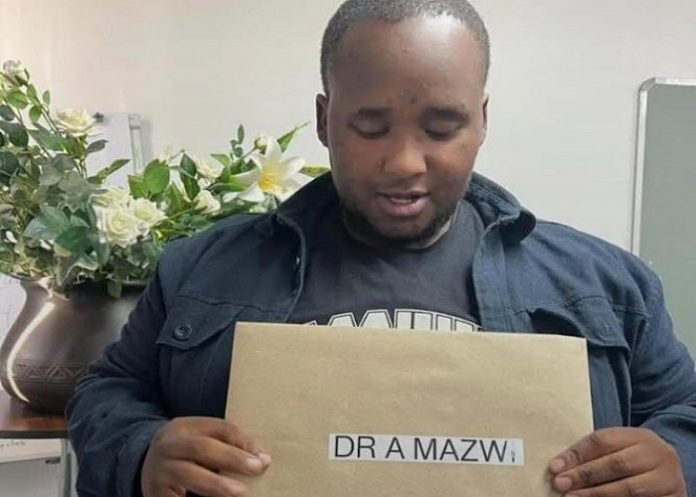

Dr Alulutho Mazwi (25), an intern in the paediatrics department Umlazi’s Prince Mshiyeni Memorial Hospital who suffered from diabetes, died a week ago after allegedly being made to work despite reporting that he was unwell.

A medical manager at the hospital has been placed on precautionary suspension following the death and Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi has asked the Ombud to open an investigation into the case.

The Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) stipulates that junior doctors should work 40 hours per week, with a maximum of 20 hours overtime, and rest periods, including a 12-hour break, between weekend shifts. However, in practise, these regulations are often ignored, and in overburdened public health facilities, junior doctors routinely work between 80 and 120 hours per week.

The harsh conditions faced by these young doctors were tragically brought back into focus last week with the death of Mazwi, who died on the same day he was supposed to be admitted to the hospital.

According to reports, Mazwi, who had collapsed twice before, had told his superiors about feeling unwell but was allegedly told that if he did not report for duty, he would have to repeat his rotation.

This was not an isolated incident, reports Yoliswa Sobuwa for Health-e News, who writes that in 2016, a junior doctor in Cape Town died in a car accident after falling asleep behind the wheel after an extended shift. That same year, junior doctors called for the HPCSA to review the 36-39-hour shifts, which were then considered standard. In response, the Western Cape Health Department introduced a 24-hour shift limit for interns.

However, junior doctors continue to report gruelling working conditions.

Questions raised

Ntokozo Maphisa, spokesperson for the KwaZulu-Natal Health Department, said that after the death of Mazwi, senior officials had visited the hospital to conduct an independent investigation.

The Sunday Tribune reports that after his death, questions were raised regarding the treatment of junior staff, especially interns, by their superiors in the hospital.

Staff and union representatives had gathered outside the hospital after the tragedy to demand accountability, with the Public Servants Association (PSA) claiming Mazwi’s deteriorating health was visible, yet he continued to work until he collapsed.

The PSA wanted an immediate precautionary suspension of implicated senior staff “who may have contributed to or ignored the intern’s situation”, claiming the death was a culmination of what it had consistently warned the department about, relating to “inhumane working conditions, autocratic leadership, and abuse of power” at the hospital.

“The PSA previously picketed and delivered memoranda to the HoD and the MEC for Health, raising concerns about the ill-treatment of staff. To date, no meaningful investigation or intervention has been conducted,” it said in a statement.

It told TimesLIVE it had previously flagged concerns about ill-treatment of staff at the hospital.

“This is not an isolated case. Many doctors and healthcare workers in KwaZulu-Natal continue to suffer under hostile, exploitive and toxic management, often working under impossible conditions without support.”

The Health and Allied Workers Indaba Trade Union (Haitu) said: “It is a common occurrence for managers to deny leave or even recall staff their leave to …patch up the shortage of staff. Haitu has received numerous grievances related to gross violations of this basic right.”

Valued

KZN Health described Mazwi, who hailed from Mthatha and who had studied medicine at Walter Sisulu University, as a “valued team member”, reports News24.

The Portfolio Committee on Health’s chairperson, Sibongiseni Dhlomo, said the young man was a dedicated intern and that Penny Msimango, the acting head of the KZN Health Department, had committed to investigate the matter.

“This young intern, and the only child of his family, died after allegedly being forced by his supervising consultant to work while critically ill. His deteriorating health was visible, yet he continued to work before collapsing during his shift.”

Mazwi had recently received a diabetes diagnosis and faced significant health challenges, Dhlomo said.

“We recognise the immense loss felt by the hospital staff who witnessed the intern’s struggle and the impact of systemic failures in our healthcare system.”

Long hours, relentless shifts

“While standard contracts for these young doctors may list 40 to 60 hours a week, this excludes the excessive overtime that is almost always required due to chronic understaffing,” said Dr Mvuyisi Mzukwa, chairperson of the South African Medical Association (SAMA).

“It’s not uncommon for interns and community service doctors to work 24 to 36 hour shifts, often with minimal or no breaks and very little supervision. Consecutive calls where a doctor works a full day, stays overnight on call, and continues into the following day still happen at many institutions.”

The consequences are serious, not only for the physical and mental health of these juniors but also for the safety of their patients. A 2024 study shows that the prevalence of burnout among doctors in South African health facilities ranges between 57.9% and 78.0%, a staggering statistic that points to a profession in crisis.”

Xolani*, a 26-year-old intern at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, describes the long hours as emotionally and physically taxing.

“We’ve been told many times that this is how you ‘earn your stripes’, so we’re led to believe it’s normal,” he told Health-e News. “It’s become normal for me to spend two days at the hospital, working with very little rest. The moment you try to take a break, you’re called for an emergency.”

Dr Cedrick Sihlangu, general secretary of the South African Medical Association Trade Union (Samatu), said the HPCSA recommends junior doctors take a break after every five hours of continuous work.

“This includes a one-hour meal break, which is considered mandatory. However, most junior doctors go for hours without even getting this break because they simply can’t afford to stop in the middle of attending to patients.”

He said that in departments like surgery, for instance, a junior doctor might be involved in a complex operation that takes up the entire day.

“There’s enormous pressure in public hospitals due to the disproportionate doctor-to-patient ratio, and unfortunately, many supervisors don’t even check if interns have had time to rest or eat,” he added.

South Africa faces a significant shortage of doctors, with a doctor-to-patient ratio of 1: 2230 (0.44 per 1000) of the population. The WHO recommends a ratio of one doctor per 1 000 people.

Mental health consequences

Samatu stresses that junior doctors are the backbone of the healthcare system, delivering essential care under extreme conditions.

“The death of Mazwi must serve as a wake-up call to all in the profession. We can no longer ignore the inhumane treatment and severe strain endured by these young doctors.”

He added that this wasn’t just about performance, it directly affects patient safety.

“Medical negligence claims, which are a growing challenge for the Department of Health, are sometimes linked to doctors working under these extreme conditions.”

SAMA’s Mzukwa said the physical toll was also severe. “Junior doctors frequently experience extreme exhaustion and dehydration while on duty. In the worst cases, mental health consequences can lead to suicide. Many suffer in silence, facing untreated mental health conditions because of stigma and the lack of accessible, confidential care.”

Reporting unsafe working conditions

Mzukwa acknowledges that while there are internal grievance processes within provincial Health Departments and some oversight by the Office of Health Standards Compliance, most junior doctors find these mechanisms ineffective.

“Reports are often ignored, and whistleblowers may face victimisation, including delayed contract renewals or threats to not be signed off at the end of their rotations,” he said, adding that without independent oversight and stronger enforcement, the current systems fail to provide real accountability or protection.

Concerns

Health MEC Nomagugu Simelane, who expressed her sadness over the death of Mazwi, said the department was struggling to come to terms with the loss of three other staff who had all died in the same week as Mazwi:

• Dr Siyabonga Zulu, a medical officer in the department of anaesthesia at Ngwelezane Hospital, died in a car accident on Sunday.

• Mvelo Cele, a radiographer at Port Shepstone Hospital, died at work days later.

• Dr Tumelo Kgaladi, from Addington Hospital’s obstetrics and gynaecology unit, died at his home.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Doctors take strain from staff shortages

How to manage frustration from working in resource-constrained institutions

Staff shortages and long waiting times plague KZN Health

Global healthcare systems struggling under increasing pressures