Actively recruiting medical students from remote areas could be the solution to addressing the imbalance between rural and urban areas, one of the toughest tasks of the National Health Insurance (NHI) plan.

In a Bhekisisa analysis, health journalist Jesse Copelyn writes that despite SA having numerous unfilled medical staff posts (in 2021, a 20% vacancy rate for doctors in clinics and a 14% vacancy rate in hospitals), the country produces more doctors than it can afford to employ.

This is because provincial health departments’ budgets have increased at a slower rate than the intake of medical students, so government hospitals “have not been able to absorb the new doctors”, says Nicholas Crisp, deputy director-general in the National Health Department tasked with implementing the NHI scheme.

“We don’t have the money to fill all vacant positions or create additional ones,” Crisp said. Instead, some provinces have slashed appointments.

In January, KZN Health, for example, issued a moratorium on the filling of posts (except for medical intern and community service positions, and those funded by special grants) “until further notice” — despite 29% of doctor jobs at clinics and 9% in hospitals being unfilled .

This was lifted in March, but solving the shortage of health professionals in the public health sector and health workers more equally among rural and urban areas remains one of the NHI’s toughest tasks.

The problem is the health budget for paid-for internships positions has not kept up with the pace at which the 10 medical schools have increased student intake.

After six years of study, students complete two-year remunerated internships at public hospitals, then a year of community service at a government facility, before they can practise as doctors.

But over the past decade, graduate numbers have increased. Between 2017 and 2020, those who began their medical internships at public hospitals increased by 61%: from 1,476 in 2017 to 2,369 in 2020.

That’s because medical schools gradually started to accept more first-year medical students from 2011, who started to graduate in 2016, who now all need internship positions. SA also sends students to Cuba for training, who do their last 18 months of education at local universities before starting internships. Cuban-trained student numbers have increased from 80 in 1997 to 650 students graduating in 2020 and 1,291 in 2021.

But provincial health departments, which cover internships and community service post costs, battle to budget for enough positions, leaving prospective doctors in limbo for placement.

Does SA have enough doctors?

SA has eight doctors for every 10,000 people, which although higher than in most other African countries, is lower than in other middle-income regions.

Internationally, countries have roughly double the number of doctors: about 18 per 10,000 people. But the problem is more complex.

When SA’s doctors per 10,000 people figure is broken down between public and private healthcare sectors, private sector patients have access to almost six times as many doctors as those using government facilities. The private sector has 17.5 doctors for every 10,000 people, the public sector three, meaning most of SA only has access to three doctors per 10,000 people, as 72% of SA’s population depends on public health.

In numbers, 15,474 doctors work in the public sector and 14,951 doctors work at private practices. This implies that about half serve 27% of its population, while the other half serves almost three-quarters.

The doctors per 10,000 people and actual doctor numbers don’t always add up, but the conclusion is the same: doctors are unequally distributed between the private and public sector.

The NHI Bill says the scheme will address the unequal distribution of doctors by buying healthcare services from private and public providers.

But efforts so far, mostly in NHI pilot districts, haven’t worked. Between 2012 and 2018, the government put out calls for private general practitioners in pilot districts where there were few public sector doctors to offer their services. Only 330 took up the offer, largely because the programme was managed badly.

“The lack of adequate planning … contracted GPs were essentially viewed as ‘subcontractors’ and could not be paid using national health department guidelines or through the government payroll system”, and the salary bill became unaffordable.

Crisp says they must be contracted in a different way. “During the pandemic, private pharmacies administered more than 6½m vaccinations: we’ve learnt the role of community pharmacies in primary healthcare.”

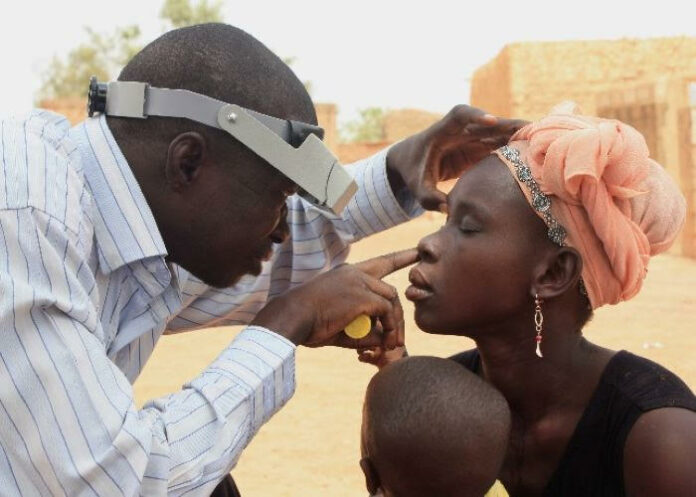

The rural problem

Analysis shows less than 3% of medical graduates end up working in rural areas 10 to 20 years after graduating. However, international evidence shows medical graduates raised in rural towns are likelier to return to work in those areas than their urban counterparts.

A 2016 SA Medical Journal study tracked several hundred young doctors for five to 10 years after graduation. Among those from rural areas, four in 10 were practising in rural towns, compared with between 5%-12% of peers from urban backgrounds.

Do medical schools have admission policies favouring rural students?

Though there are policies encouraging universities to address racial inequalities, there is no pressure to boost admissions from rural areas, says Lionel Green-Thompson, dean of the University of Cape Town (UCT) medical school.

Only some medical schools have explicit policies to increase student intake from remote areas. Wits University reserves 20% of its places for top-performing learners from rural areas, while the University of the Free State gives additional points for students from rural schools. Stellenbosch University has a rural clinical school, training medical students in their final year in an attempt to admit more students from rural areas.

But admissions from rural schools have their own challenges.

Because these students often have fewer educational/financial resources, they face stressors – like fear of failing and financial and accommodation problems – making it harder to complete their studies.

A programme from the KZN Umthombo Youth Development Foundation shows what can be done. Hundreds of promising students from poor rural schools were mentored and later offered scholarships for a health sciences degree, provided they return to practise for some time in the areas where they were initially interviewed.

The programme has achieved a pass rate of 92% annually, most students passing their degrees in the minimum period or minimum plus one year.

Managers at poor rural hospitals in KZN, which previously struggled for staff, say the programme had given them a consistent supply of health professionals for the first time, many staying on longer as they built ties with the community that had raised them.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

SA’s doctor shortage has worsened substantially in past 3 years

SA’s public hospital staffing disaster: 12,000 vacancies for nurses and doctors

‘Outraged’ SAMA threatens court action over placement of almost 5,000 junior doctors