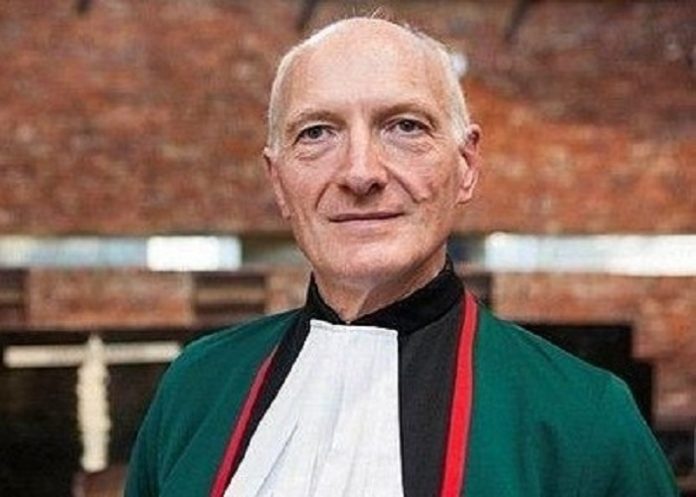

HIV made him expect to die at 40. Now 73, retired Constitutional Court Justice Edwin Cameron remembers when being told you had HIV meant watching gay men die “in their tens of thousands”, with nothing doctors could do to save them.

In 1999, he came out with his HIV status after two deaths made his silence impossible: anti-apartheid activist Simon Nkoli, who died of Aids, and HIV activist Gugu Dlamini, who was attacked and killed weeks after stating that she had HIV.

Three heart stents, high blood pressure, irregular heartbeat – Cameron’s medical chart reflects research showing HIV makes you grow older faster.

Now researchers are learning what happens when people with HIV grow old: they develop heart disease, diabetes and other conditions four times faster than those without it.

Writing in Bhekisisa, Mia Malan tells us what HIV has taught Edwin Cameron.

In 1997, Cameron looked at himself in the bathroom mirror and stuck out his tongue. He was terrified at what he saw.

His mouth was dotted in flecks of white; a fungus, the sort of spores that belong on dead bodies, he thought. Breathing was becoming difficult. He was having trouble swallowing, had lost his appetite and dropped 15kg. He was beginning to look emaciated, and people were noticing.

Even before the x-rays came back from the radiologist, he knew he had pneumocystis pneumonia, or PCP, a form of pneumonia caused by a fungus that infects the lungs. Unless it was treated with a heavy course of strong medication, it would kill him.

He knew what that meant, just as he knew what he was looking at on his tongue was oral thrush. Both were common diseases that ravaged people with extremely weak immune systems.

The judge could no longer ignore what was happening: HIV, a secret his body harboured for 12 years, had finally turned to full-blown Aids.

The medicines that could save his life cost R4 500 a month, about one-third of the salary he collected as a High Court judge in Johannesburg. He would pay cash: back then, these sorts of drugs were not freely available in public clinics, and medical aids did not cover them.

By then, treatment was a combination of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), which had recently started successfully treating patients in the US. But the cost of the medicine put treatment completely out of reach for all but a few Africans – a searing injustice that put a steep price on life which never escaped Cameron, and would drive much of his life’s work.

It would be seven more years of court battles, of a government paralysed with HIV denialism, of relentless activism, demonstrations, demands for drug companies to lower costs, and millions of people lost to HIV before the drugs were made free in government clinics.

But on 7 November 1997, at his home in Brixton, the judge would swallow his privilege. By his side were researcher Morna Cornell and activists Mark Heywood and Zackie Achmat (all of whom would lead HIV work) as he ingested the first of what would be tens of thousands of pills over the next 28 years.

That December, Cameron walked up Table Mountain. It was nothing short of a miracle.

Darkest days

If you had told him then that he’d be sitting in his home in Sandton at 73, six years after stepping down from the Constitutional Court where he served for 11 years, recounting those terrifying times, he would not have believed you.

“I was 33 when I was told I had HIV and 32 when I was infected,” he recalled. “Undoubtedly, I would never be 40. I would never see a democratic, free South Africa. I would never become a judge – despite my terrible criticism of the apartheid judiciary, I hoped to do so in a democratic South Africa.”

Cameron talked about the darkest days of the disease, which was then called Grid, or gay-related 80s before baring its teeth on the world. Today in South Africa, four out of every 10 new infections are girls and women aged 15 to 24, even though they make up only about 8% of the total population.

“I was infected with HIV 40 years ago at Easter, 1985. I was told by my doctor about 20 months later. Gay men like myself in their early 30s… were dying in their tens of thousands on the West and East Coasts of America, in the Midwest, Western Europe, Australia, and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

“They could give palliative treatments and maybe antibiotics for some of the secondary diseases, the symptomatic presentations of the collapse of your immune system. But there was nothing that could be done, so you faced a certain death.”

The first generation

Cameron was one of the first South Africans to take what were new, lifesaving drugs, and is proof of their ability to sustain a long life. It is through those like him, who had access to the drugs early on, that medical science is now able to not just keep alive people with HIV but also witness the effects on people growing old with it.

Just by living longer, we become more susceptible to developing non-communicable diseases (NCDs), but studies have shown that people with HIV are four times as likely to get NCDs as they age faster – during the period that they’re not on treatment – than those without it. And they are often hit with multiple NCDs at the same time.

Cameron is strict about adhering to his ARVs, careful about what he eats, exercises regularly, and is an avid cyclist. Yet you can see his reflection in those findings.

“I lead a healthy lifestyle, and yet I had blockages in my cardiac arteries. I got three stents in 2017. I’ve got high blood pressure, all of it controlled. And this year, I had atrial fibrillation. I’m enormously grateful to have access to the quality of medical care that is keeping me healthy. But… I have a sense of vulnerability.”

Studies have found that the sooner someone starts treatment, the better. But the longer you wait to take ARVs, the faster your body ages.

Cameron lived with HIV for 12 years before he could start treatment. Back then, ARVs were prescribed based on how low your CD4 count was.

Over the years, it became clear that the faster someone starts treatment after infection, the better. Since 2017, ARVs in South Africa have been given as soon as someone tests positive – to keep their viral load low enough so the virus cannot be transmitted.

He still looks back to that day in November, 28 years ago, when he cradled his first dose in his hands.

“I feel a profound and humble sense of deep gratitude for living, for the medical science that brought ARVs and, most importantly, for the activism that insisted these drugs be developed. Without the angry rage of men like myself in North America, and without the activism of Zackie in starting the Treatment Action Campaign in December 1998…more than six million people like myself are now on ARVs and owe their lives and wellness and healthiness to ARVs.”

Charter of Rights

HIV has shaped Cameron’s career as well as his life. Before Nelson Mandela appointed him as a judge to the High Court in 1994, he was a human rights lawyer at the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (Cals) at Wits University, where he founded the Aids Law Project (which would become SECTION27), co-founded the Aids Consortium and helped draft the Charter of Rights on Aids and HIV.

Part of his identity, though, came with the stigma attached to it.

“Worse than the loss of a vision of your life ahead was the internal shame I felt. That’s why I speak about internalised stigma – because I blamed myself… there’s a level of self-blame that is terribly debilitating.”

His work at Cals helped him to partly come to terms with that. There, while working with the National Union of Mineworkers on Aids/HIV legal codes as the epidemic was exploding in South Africa, he began meeting others with HIV. People who weren’t gay, white men like him.

“They were black, they were women, they were married to opposite sex partners who were mine workers who were away for substantial periods of the year. Some told me they’d never had sex with anyone apart from their husbands. Yet they felt the same shame I did.

“I’m not comparing our situations because I was enormously privileged, but that made me see things differently – that it was not about queerness or gayness or having gay sex or having too much sex.”

Stigma was one of the reasons he waited as long as he did to speak out about his HIV, which he announced in 1999, when he was up for consideration for the Constitutional Court.

His coming out followed two pivotal deaths: Simon Nkoli, the openly gay anti-apartheid and gay rights activist, who died of Aids at 41; and, soon after, HIV activist Gugu Dlamini, a 36-year-old who died, not of Aids, but was attacked and killed three weeks after publicly announcing she had HIV.

Cameron knows first hand how difficult it is to come out and say you have HIV. Still, he cannot conceal his disappointment in some of South Africa’s “silent people”, the public figures who have not declared their status, “our elite, our politicians, our soccer players, our entertainers, our public figures, our professors at university”.

“Should someone speak out about having survived breast cancer, cervical cancer, liver cancer? I would never say you should speak out about having had any life-threatening disease, but it would be enormously helpful and normalising in what is in our country a normal disease. Because when 13% of people are living with a potentially life-threatening disease, it’s normal.”

And that, he says, would help get us past the stigma that keeps people away from clinics, from being tested, from taking the medicines that can save their lives. From keeping that past scourge of certain death at bay.

“(Having HIV has) made me deeply conscious of how important social activism and civic action are. Our institutions of government and our instruments of government are important, but they have to be shaped and pressured and demanded upon by civil society action.”

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

TAC’s symbolic march on Concourt — to thank it for HIV ruling

Why independent healthcare for prisoners is vital – Judge Edwin Cameron

Mbeki slammed for repeating ‘misleading’ HIV/Aids statements

Make vaccinations mandatory, says retired ConCourt judge