Initially, the World Health Organization stated that SARS-CoV-2 was not transmitted through the air. It took two years to correct its mistake and in the process sowed confusion and raised questions about what will happen in the next pandemic, writes Australian journalist Dyani Lewis in Nature.

Nature reports that on the WHO website, a page titled Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted? was edited to say a person can be infected “when infectious particles that pass through the air are inhaled at short range”, known as “short-range aerosol or short-range airborne transmission”.

It adds transmission can occur through “long-range airborne transmission” in poorly ventilated or crowded indoor settings, “because aerosols can remain suspended in the air or travel farther than conversational distance”.

“It was a relief to see them finally use the word ‘airborneʼ,” says University of Colorado Boulder aerosol chemist Jose-Luis Jimenez.

The statement marked a shift for the WHO, which early in the pandemic tweeted, “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne”.

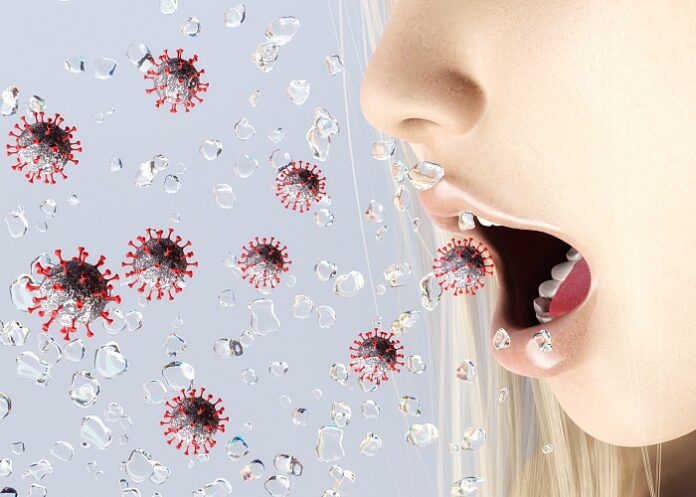

Back then, the agency maintained the virus spreads mainly through droplets when a person coughs, sneezes or speaks, based on old infection-control teachings about how respiratory viruses are transmitted. The guidance recommended “social distancing” of more than 1m – within which these droplets were thought to fall to the ground – along with handwashing and surface disinfection to stop transfer of droplets to the eyes, nose and mouth.

Only on 20 October 2020 did the agency acknowledge that aerosols – tiny specks of fluid – can transmit the virus, but the WHO said this was a concern only indoors and in crowded, inadequately ventilated spaces. Over the next six months, the agency gradually altered its advice to say aerosols could carry the virus for more than 1m and remain in the air.

But this latest tweak is its clearest statement yet about airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2, placing the virus among a select group of ‘airborne’ infections like measles, chickenpox and tuberculosis.

The change brings the WHO’s messaging in line with what aerosol and public-health experts have wanted it to say since the outbreak’s earliest days.

Interviews conducted by Nature with disease transmission specialists suggest the WHOʼs reluctance to accept evidence for airborne transmission was based on assumptions about how respiratory viruses spread, and because the agency relies on a narrow band of experts who haven’t studied airborne transmission. They say it resisted a precautionary approach that could have protected countless people.

WHO inaction led to health agencies worldwide being similarly sluggish in tackling the airborne threat. The WHO also failed to adequately communicate its changing position, and “didn’t emphasise early enough the importance of ventilation and indoor masking”.

Lidia Morawska, an aerosol scientist at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, spearheaded several efforts to convince the WHO of the airborne threat, which was “obvious” from February 2020.

But Dale Fisher, an infectious-diseases physician at Singapore’s National University Hospital and chair of the WHO’s Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network steering committee, doesn’t think confusion over whether the virus is airborne has had a defining impact on how the pandemic has played out, while other researchers also defend the agency’s response. “I don’t think anybody dropped the ball, including WHO,” says Mitchell Schwaber, an infectious-diseases physician at Israel’s Ministry of Health and external adviser to the WHO.

Tension in the air

In March 2020, Morawska contacted dozens of colleagues to spread the word about the airborne threat of SARS-CoV-2. On 1 April 2020, the group emailed Michael Ryan, head of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, and Maria Van Kerkhove, technical lead of the WHO’s COVID-19 response.

Two days later, the group attended a video conference with the Health Emergencies Programme and the Infection Prevention and Control Guidance Development Group (IPC GDG) – some 40 clinicians. By then, more than 1m people had been infected with SARS-CoV-2; 54,000 had died.

Morawska presented “solid evidence” that people were being infected even when they were more than 1m, as recommended by the WHO, from a contagious individual, and proof from years of mechanistic studies showing mucus in the airways can spray into aerosols during speech and accumulate in stagnant rooms.

Morawska felt rebuffed by the WHO. She and others who study aerosols and airborne disease transmission say the IPC GDG is ill-equipped to assess this type of transmission because most of its members lack expertise in how airborne contagions spread. At the time of the 1 April meeting, no one in the IPC GDG had studied this type of disease transmission.

“With a new disease, you had better include everyone,” says Yuguo Li, a University of Hong Kong building environment engineer, whose study of the SARS outbreak in 2002–03 had concluded the virus probably spread through the airborne route.

Schwaber, who chairs the IPC GDG, recalls: We took very seriously the issues they raised at the meeting.” At the time, he adds, evidence suggested airborne precautions in hospitals, including masks for staff, visitors and patients, were unnecessary.

Mark Sobsey, University of North Carolina environmental microbiologist and a member of the IPC GDG, says initially, concerns relayed to the WHO about airborne transmission were “largely unfounded”, lacking credible evidence. Epidemiological data from investigations were “especially weak”.

Trish Greenhalgh, a primary-care health researcher at Oxford University, UK, said the IPC GDG members were guided by dominant thinking about how infectious respiratory diseases spread; this turned out to be flawed and could be inaccurate for other viruses, too.

These biases led the group to discount relevant information, and it concluded airborne transmission was rare or unlikely.

That viewpoint is clear in a commentary by the IPC GDG published in August 2020. The authors dismissed research using air-flow modelling, case reports describing possible airborne transmission, labelling them “opinion pieces”.

The group failed to look at the whole picture, says Greenhalgh. “Youʼve got to explain all the data, not just what youʼve picked to support your view.” The airborne hypothesis was the best fit for all the data available, she says.

One example is the propensity for the virus to transmit in “superspreader events”, where numerous individuals are infected at a single gathering.

“Nothing explains these superspreader events except aerosol spread,” she says. There was also mounting evidence that indoor spaces posed a greater risk of infection than outdoor. An analysis of outbreaks recorded up to August 2020 showed people were more than 18 times as likely to be infected indoors as outdoors.

Although the WHO played down the risk of airborne transmission, it did invite Li to become a member of the IPC GDG after he spoke to the group in mid-2020.

Still, he is disappointed it took them until October 2020 to acknowledge aerosols play a part in disease transmission in community settings.

It wasn’t until the end of April 2021 that long-range aerosol transmission was added to the agency’s website about how the virus spreads; the term airborne wasn’t added until December 2021.

Conservative approach

Some scientists say the WHO’s eventual decision to classify SARS-CoV-2 as airborne, was momentous, flying in the face of the established view of respiratory virus transmission when the pandemic began – that nearly all infectious diseases are spread by droplets, and not airborne.

Yet many question why, when concerns were growing that SARS-CoV-2 could be airborne, the WHO didn’t adopt a precautionary approach by acknowledging the possibility of different risks.

And in May 2021, the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR), established by the WHO a year earlier to review the agency’s actions at the start of the pandemic, chastised it for not applying the precautionary principle to another crucial aspect of COVID-19 transmission – whether it could spread from human to human.

Sobsey says the WHO did adopt the precautionary principle, partly because of the advice from aerosol scientists. That’s why, he says, the agency stated in July 2020 that airborne transmission couldn’t be ruled out, and why it started placing more emphasis on ventilation as a protective measure, even though evidence was weak at the time.

Critics say that even two years into the pandemic, the WHO still hasn’t clearly communicated the risks from airborne transmission. So governments worldwide spent much of the pandemic focusing on hand washing and surface cleaning, instead of ventilation and indoor masking.

The agency defends its actions. In a statement to Nature, a spokesperson said: “WHO has sought expertise from engineers, architects and aerobiologists, and expertise in infectious diseases, infection prevention and control, virology, pneumology and other fields, since the start of the pandemic.

“As evidence on COVID-19 transmission has expanded, we have learnt that . . . aerosols also play a role in transmission, and adapted guidance and messages to reflect this.”

Nature article – Why the WHO took two years to say COVID is airborne (Open access)

World Health Organization (WHO) website How does COVID-19 spread between people? (Open access)

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

New CDC guideline admits that COVID-19 transmission is airborne

CDC update on airborne transmission of COVID-19

Airborne spread of COVID-19 and ventilations factors — 2 studies

WHO changes tack on airborne spread of COVID-19

Airborne transmission is dominant route for spread of COVID-19 — US analysis