Athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities who were previously considered ineligible for competitive sports participation, may take part quite safely, new evidence indicates.

A joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology says shared decision-making is essential between clinicians and athletes, and also provides guidance on how to assess the individual’s risks. It adds that more research is needed to better understand how competitive sports participation affects overall health among athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities, as well as how social disparities affect them.

The joint scientific statement was published in AHA’s peer-reviewed journal Circulation and simultaneously in JACC, the flagship journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Clinical Considerations for Competitive Sports Participation for Athletes with Cardiovascular Abnormalities includes significant changes based on evidence from the past decade; the previous scientific statement was published in 2015.

“In the past, there was no shared decision-making about sports eligibility for athletes with heart disease. They were just automatically prohibited from participating in sports if almost any cardiac issue were present,” said writing group chair Jonathan H Kim, an associate professor of medicine and director of sports cardiology at Emory University School of Medicine.

“This new statement reviews best clinical practices for athletes with certain cardiovascular conditions and how healthcare professionals can guide these athletes – from children to Masters athletes – in a shared decision-making discussion about potential risks and rewards.”

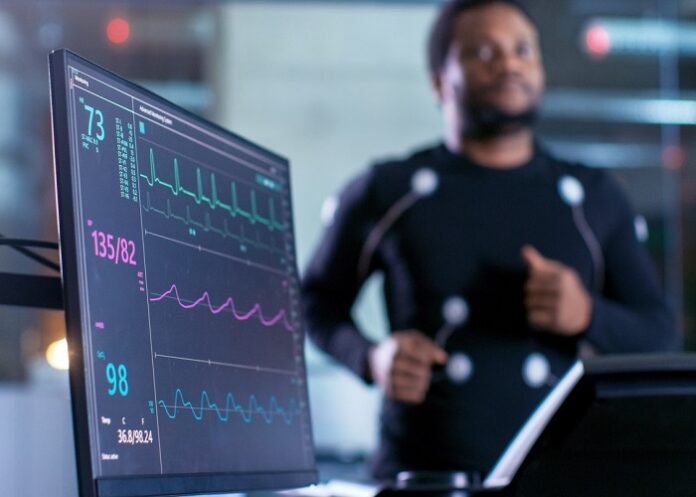

The change in messaging reflects advancements in the medical community’s understanding of the “athlete’s heart”, which captures the complex structural, functional and electrical cardiac adaptations that happen in response to habitual exercise training.

Studies in the past 10 years about many cardiac conditions, from congenital heart disease to arrhythmias and more, indicate the risks are not as high during competitive sports participation as previously thought and provide an evidence-based path for safe return-to-play as a possible outcome for many athletes.

While previous scientific statements classified sports into specific categories, this revision acknowledges that sports training is dynamic – a continuum of strength and endurance that is athlete-specific. It takes into consideration that not all athletes train the same, not all sports are alike, and not all cardiac conditions confer identical risk.

The writing group defined competitive athletes as professional and recreational athletes who put a high premium on achievement and train to compete in not only team sports but also individual sports, like marathons and triathlons.

This new scientific statement covers athletes not included in previous documents. For example, there is a section dedicated to assessing risk in Masters athletes (people 35 and older) with coronary disease, atrial fibrillation, enlarged aortas and valve disease.

There are also updates for extreme sports athletes, including those who scuba dive or exercise at high altitudes. The statement also addresses how to better inform a healthy person who wants to play competitive sports during pregnancy about potential risks, given the significant shift in physical and metabolic state brought about by pregnancy.

“We acknowledge that there are times when the risks of competing are much higher than the benefits for athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities,” Kim said.

New evidence informs updates

• The statement reinforces the importance of pre-participation cardiac screening for school athletes. Healthcare professionals should begin with the Association’s 14-point evaluation, which includes a physical exam with blood pressure measurement and questions about family and personal health history. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is also a reasonable screening for asymptomatic athletes as long as appropriate expertise in athletic ECG interpretation is provided. In addition, equitable resources for subsequent clinical evaluations of abnormal ECGs should be available to all athletes included.

• For athletes taking blood thinning medications, the new statement offers more guidance about how healthcare professionals can assess risk based on specific types of sports. Certain activities with a higher risk of trauma and bleeding, such as rugby or competitive cycling, must be considered for athletes taking blood-thinning medications.

• Previously, people with cardiomyopathies were told not to compete in sports: the authors of this update make it clear that a uniform mandate of sports restriction should not be applied and, under clinical guidance, participating in sports may be reasonable with some genetic cardiomyopathies.

• The previous recommendation for people with myocarditis was that they should not participate in sports for three to six months; however, this was solely based on expert opinion as there were no data to support that. Current research suggests the condition often improves within less than three months, so many of these athletes may safely return to competitive sports sooner than previously thought. Individual assessment and clinical guidance are necessary in this setting.

• Not all young athletes with aortopathy, or abnormalities of the aorta, should be advised to restrict sports participation. The document offers more details about how to evaluate athletes with an enlarged aorta.

• The statement addresses the genetic heart rhythm disorder catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, a condition where there was previously a uniform disqualification from competitive sports. For athletes who receive appropriate expert care with clinical risk stratification, competitive sports could be considered.

Knowledge gaps and future research needs

Researchers and healthcare professionals need more information about how athletes with cardiovascular disease progress during continued sports participation – and whether the sport improves or harms their overall health.

Established in May 2020, the Outcomes Registry for Cardiac Conditions in Athletes (ORCCA) study is the first prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, observational cohort study designed to monitor clinical outcomes in athletes with potentially life‐threatening cardiovascular conditions.

In addition, there are significant gaps in information for competitive athletes with cardiovascular conditions who are affected by social disparities of health.

“We know that if you look at sudden cardiac death risk in young athletes, it does appear that young, black athletes have a higher risk, but we don’t know why,” Kim said. “We have to look at social disparities because it is a very reasonable hypothesis … that disparities play an important role in … health outcomes for athletes as they do in the general population.”

Scientific statements outline what is currently known about a topic and what areas need additional research. While they inform the development of guidelines, they do not make treatment recommendations. AHA guidelines provide the Association’s official clinical practice recommendations.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Extreme exercise and middle-aged athletes’ hearts

Study shows obvious gender bias in patient advice on heart disease

AEDs saves lives at sports and fitness centres

Supervised exercise training helps patients with heart failure