Annual screening for ovarian cancer can detect tumours earlier but does not save lives, one of the largest studies ever conducted on the UK general population suggests.

The study, published in The Lancet, by researchers at University College London, analysed data from more than 200,000 postmenopausal women, recruited to the trial between 2001 and 2005. Half of the women underwent no screening, while the remainder were either offered a yearly vaginal ultrasound scan, or an annual blood test to detect a cancer-related protein called CA125, followed by an ultrasound scan for those with altered levels of this protein.

The study found that although blood test screening picked up 39% more cancers at an early stage (stage I/II), compared with the vaginal ultrasound and no screening groups, this did not translate into a reduction in deaths from the disease.

“Either we need to find more individuals at an earlier stage of disease and fewer individuals with late-stage disease through screening, and/or this disease is such that even if you did that, the biology of [ovarian cancer] means that it’s going to be aggressive whatever you do, even if you find it at an early stage,” said Prof Mahesh Parmar, the director of the Medical Research Council clinical trials unit at UCL and a senior author on the paper.

The researchers did notice that those women identified through the blood test did not respond as well to standard treatment as those women who did not undergo screening but whose cancers were identified early based on their symptoms.

Disappointing as the results are, Parmar emphasised that in women who do have symptoms of ovarian cancer, early diagnosis, combined with significant improvements in the treatment of advanced disease over the past 10 years, could still save many lives.

“Our trial showed that screening was not effective in women who do not have any symptoms of ovarian cancer; in women who do have symptoms, early diagnosis, combined with this better treatment, can still make a difference to quality of life and, potentially, improve outcomes,” he said. “On top of this, getting a diagnosis quickly, whatever the stage of the cancer, is profoundly important to women and their families.”

The team is conducting further analysis to look at whether earlier detection may result in less extensive surgery or chemotherapy.

Other screening methods are also being developed, but it could take years to know if these would save more lives. For now, the focus should be on improving awareness of the most common symptoms and ensuring that women who experience them are promptly referred to an oncologist, said Usha Menon, a professor of gynaecological cancer at UCL, who led the study.

introducing a national cancer screening programme is a mortality benefit. Of course this is key — saving lives. It's disappointing that this research programme did not show a reduction in mortality from ovarian cancer and so can't be recommended as a national screening programme. However, the impact it had on earlier diagnosis is impressive and important.

"Ovarian cancer is so often diagnosed at stage 3 or 4 and shifting diagnosis one stage earlier makes a huge difference to both treatment options and quality of life. Earlier diagnosis will often reduce the amount and intensity of treatment, and this makes all the difference to women and their families who are living with cancer. It may have also given them more precious time with their loved ones."

The Guardian</strong> notes that although the finding is a blow to those affected by ovarian cancer, the hope is that earlier diagnosis could reduce the amount and intensity of treatment that women go through.

About 7,500 British women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer each year and 4,000 die from it, making it the deadliest gynaecological cancer. The lack of any single telltale symptom means the disease is often not diagnosed until it is at a late stage – and prompt diagnosis is crucial because although 80-90% of women whose cancer is detected early survive for at least five years, that figure falls to 25% when the disease is spotted late.

The hope was that screening healthy women for signs of ovarian cancer might improve these survival rates, as population screening for cervical cancer has done.

“Symptoms of ovarian cancer can be quite vague and similar to symptoms caused by less serious conditions, which can make spotting the disease tricky,” said Michelle Mitchell, Cancer Research UK’s chief executive. “Whether it’s needing to go to the toilet more often, pain, bloating, or something else, raise it with your GP – in most cases it won’t be cancer but it’s best to get it checked out.”

Study details

Ovarian cancer population screening and mortality after long-term follow-up in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a randomised controlled trial

Authors: Usha Menon, Aleksandra Gentry-Maharaj, Matthew Burnell, Naveena Singh, Andy Ryan, Chloe Karpinskyj, Giulia Carlino, Julie Taylor, Susan K Massingham, Maria Raikou, Jatinderpal K Kalsi, Robert Woolas, Ranjit Manchanda, Rupali Arora, Laura Casey, Anne Dawnay, Stephen Dobbs, Simon Leeson, Tim Mould, Mourad W Seif, Aarti Sharma, Karin Williamson, Yiling Liu, Lesley Fallowfield, Alistair J McGuire, Stuart Campbell, Steven J Skates, Ian J Jacobs, Mahesh Parmar.

Published in The Lancet, May 2021

The Lancet Summary

Background

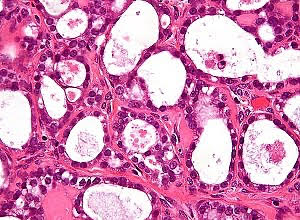

Ovarian cancer continues to have a poor prognosis with the majority of women diagnosed with advanced disease. Therefore, we undertook the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) to determine if population screening can reduce deaths due to the disease. We report on ovarian cancer mortality after long-term follow-up in UKCTOCS.

Methods

In this randomised controlled trial, postmenopausal women aged 50–74 years were recruited from 13 centres in National Health Service trusts in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Exclusion criteria were bilateral oophorectomy, previous ovarian or active non-ovarian malignancy, or increased familial ovarian cancer risk. The trial management system confirmed eligibility and randomly allocated participants in blocks of 32 using computer generated random numbers to annual multimodal screening (MMS), annual transvaginal ultrasound screening (USS), or no screening, in a 1:1:2 ratio. Follow-up was through national registries. The primary outcome was death due to ovarian or tubal cancer (WHO 2014 criteria) by June 30, 2020. Analyses were by intention to screen, comparing MMS and USS separately with no screening using the versatile test. Investigators and participants were aware of screening type, whereas the outcomes review committee were masked to randomisation group. This study is registered with ISRCTN, 22488978, and ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00058032.

Findings

Between April 17, 2001, and Sept 29, 2005, of 1 243 282 women invited, 202 638 were recruited and randomly assigned, and 202 562 were included in the analysis: 50 625 (25·0%) in the MMS group, 50 623 (25·0%) in the USS group, and 101 314 (50·0%) in the no screening group. At a median follow-up of 16·3 years (IQR 15·1–17·3), 2055 women were diagnosed with tubal or ovarian cancer: 522 (1·0%) of 50 625 in the MMS group, 517 (1·0%) of 50 623 in the USS group, and 1016 (1·0%) of 101 314 in the no screening group. Compared with no screening, there was a 47·2% (95% CI 19·7 to 81·1) increase in stage I and 24·5% (−41·8 to –2·0) decrease in stage IV disease incidence in the MMS group. Overall the incidence of stage I or II disease was 39·2% (95% CI 16·1 to 66·9) higher in the MMS group than in the no screening group, whereas the incidence of stage III or IV disease was 10·2% (−21·3 to 2·4) lower. 1206 women died of the disease: 296 (0·6%) of 50 625 in the MMS group, 291 (0·6%) of 50 623 in the USS group, and 619 (0·6%) of 101 314 in the no screening group. No significant reduction in ovarian and tubal cancer deaths was observed in the MMS (p=0·58) or USS (p=0·36) groups compared with the no screening group.

Interpretation

The reduction in stage III or IV disease incidence in the MMS group was not sufficient to translate into lives saved, illustrating the importance of specifying cancer mortality as the primary outcome in screening trials. Given that screening did not significantly reduce ovarian and tubal cancer deaths, general population screening cannot be recommended.

Full study in The Lancet (Open access)

Full The Guardian report (Open access)

See also from the MedicalBrief archives:

Most UK women mistakenly believe pap smear will detect ovarian cancer

Newer oral contraceptives linked to reduced ovarian cancer risk