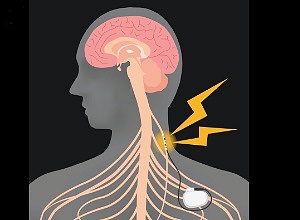

Vagus nerve stimulation in patients who had moderate-to-severe loss of arm function after suffering from ischaemic stroke at least 9 months before enrolment, resulted in improved arm function, found a small but 'well-designed' Dutch study in The Lancet.

Anne van der Meij and Marieke JH Wermerat at the Leiden University Medical Centre in The Netherlands write in The Lancet:

Therapeutic options for ischaemic stroke have greatly improved with the introduction of intravenous thrombolysis in 1995 and endovascular therapy in 2015. Despite these reperfusion therapies, stroke is still one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, which emphasises the need for supplemental therapeutic strategies.

Vagus nerve stimulation is an established therapy for epilepsy and has expanded its spectrum to the treatment of cluster headache and migraine in the past 3 years. Vagus nerve stimulation, delivered either invasively or non-invasively, is also being increasingly investigated in ischaemic stroke. In the chronic phase after stroke, vagus nerve stimulation combined with motor rehabilitation improves limb function in rats, probably by the enhancement of neuroplasticity caused by the release of neurotransmitters through stimulation.

In 2016, the first-in-human study on vagus nerve stimulation in the subacute stage of ischaemic stroke was done in 21 patients with arm weakness, showing that vagus nerve stimulation in combination with rehabilitation was feasible and safe.

In the VNS-REHAB trial, Jesse Dawson and colleagues investigated in 108 patients who had moderate-to-severe loss of arm function after suffering from ischaemic stroke at least 9 months before enrolment whether rehabilitation combined with active vagus nerve stimulation would result in improved arm function. Participants were randomly assigned to 6 weeks of intensive in-clinic rehabilitation, combined with active vagus nerve stimulation (VNS group; 64% men vs 36% women, mean age 59·1 years [SD 10·2]) or sham stimulation (control group; 65% vs 35%, 61·1 years [9·2]). All patients received an implanted vagus nerve stimulation device. Primary outcome was assessed with the Fugl-Meyer Assessment Upper Extremity (FMA-UE) score, a grading scale of 66 points measuring sensorimotor function of the arm. After 6 weeks, the mean change in FMA-UE score was 5·0 points (SD 4·4) in the VNS group and 2·4 points (3·8) in the control group (between group difference 2·6, 95% CI 1·0–4·2). Furthermore, 90 days later, 23 (47%) of 53 patients in the active group had a clinically meaningful response (increase of ≥6 points) compared with 13 (24%) of 55 patients in the control group (p=0·01).

The VNS-REHAB trial was well designed. The baseline characteristics of the two arms were comparable despite the limited number of participants, and follow-up was complete. By using sham stimulation, participants remained largely unaware of the treatment they were given. This strategy is important because both placebo and nocebo effects have been reported after neuro-stimulation. In the control group, there was a clinically meaningful response of 24% after treatment. Although this finding could be the result of the standard rehabilitation, it might also indicate that sham stimulation itself could have a small stimulating effect, as previously described.

However, the improvement in the active group was two to three times higher and, most importantly, the positive effect of vagus nerve stimulation was consistent over all outcome measures with a number to treat for the primary outcome of only four.

Still, several questions remain. Because of the small sample size, no subgroup analyses could be done. Therefore, it is unknown whether certain patients benefit more from stimulation than others. As the mechanisms underlying neuroplasticity might be age and sex dependent, future research on how vagus nerve simulation might affect women versus men, or among different age groups, is necessary. It is not known either if the effect of stimulation is persistent over time.

Although preclinical evidence suggests that stimulation facilitates long-term synaptic changes, follow-up data of the VNS-REHAB study are needed to confirm this. The interpretation of improvement of functional outcome scores and their translation to a clinically meaningful effect are often a matter of debate.

The authors tackled this issue by doing a post-hoc analysis that investigated different FMA-UE thresholds besides the chosen 6 points or more. This post-hoc analysis confirmed the higher response rate with vagus nerve stimulation for the thresholds 4 points or more and 5 or more.

The threshold of 7 points or more also showed a better response rate with vagus nerve stimulation, albeit not statistically significant. Lastly, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation methods could facilitate implementation of this technique in clinical practice. However, it is uncertain if the stimulation effects of non-invasive and invasive vagus nerve stimulation are comparable in this setting.

The fact that vagus nerve stimulation was beneficial for up to 10 years after stroke (mean time after stroke in the trial was longer than 3 years) is remarkable and suggests that vagus nerve stimulation has an effect on plasticity by enhancing neuro-modulatory circuits during training and not by stroke-induced plasticity. Besides stimulation of chronic neuroplasticity, vagus nerve stimulation might improve brain tissue recovery by inhibiting spreading depolarisations and neuroinflammation in the acute phase after stroke.

Currently, trials are underway that investigate the safety (NCT03733431) and the effect on penumbra recovery (NCT04050501) of vagus nerve stimulation in acute ischaemic stroke.

After the treatment successes in the acute phase, the VNS-REHAB opens the door to treatment strategies in the post-stroke phase. With the advent of nerve stimulating therapies, including the trial on sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation published in The Lancet in 2019, an exciting potential new era in the management of stroke has started.

Full report in The Lancet (Open access)

See also MedicalBrief archives:

Vagus nerve stimulation and stroke recovery

Daily ‘tickling’ of the vagus nerve may improve mood and sleep

Nerve stimulation restores some consciousness after 15 years of PVS

Stimulation of vagus nerve to treat rheumatoid arthritis pain