A newly published book, edited by Professors Katijah Khoza-Shangase and Amisha Kanji, seeks to re-imagine clinical practice that is Afrocentric and hence likely to yield more positive outcomes on this continent.

In South Africa it is estimated the prevalence of hearing impairment is four to six in every 1 000 live births in the public healthcare sector. This is double the rate documented for the private healthcare sector, where three in every 1 000 has been estimated.

Early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) has been extensively researched internationally, with a major focus on the efficacy of early identification through universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) programmes. However, most of this research has been conducted in high-income countries, and is not easily generalisable to low and middle-income regions like Africa, which differ in populations, resources (human, equipment), health priorities, disease, as well as neonatal protocols.

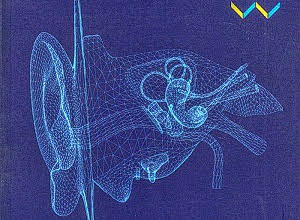

With EHDI being a significant need for Africa, given the global prevalence and incidence of childhood hearing impairment, a newly published book (edited by Professors Katijah Khoza-Shangase and Amisha Kanji) and titled Early Detection and Intervention in Audiology: An African Perspective (published on Open Access), seeks to direct the South African Speech-Language and Hearing (SLH) Professions Board of the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) to re-imagine clinical practice that is Afrocentric, and likely to yield more positive outcomes.

Khoza-Shangaze’s previous book, Black Academic Voice: The South African Experience won the 2020 Humanities and Social Sciences Award (Non-fiction category),

Khoza-Shangase said that they have deliberately adopted an African rather than a South African perspective for several reasons. First, the contextual realities under which healthcare delivery occurs are similar across the African continent. These include:

- resource constraints

- reliance on international aid and guidelines for some health care initiatives

- inadequate human resources across sub-Saharan African health systems, resulting in the use of task-shifting in attempts to increase access

- negative impact on health care systems of the high burden of diseases like HIV/Aids and tuberculosis

- challenges in terms of the social determinants of health.

Second, borders across Africa are porous. Migration due to socio-political and economic reasons is common and affects healthcare planning, implementation and monitoring. Third, the influences of linguistic and cultural diversity on seeking and delivering healthcare are arguably similar across the African continent in terms of cultural beliefs and how illness is understood, as well as linguistic differences between patients, nurses and doctors.

Khoza-Shangase writes:

EHDI is the gold standard for practising audiologists and the families of infants and children with hearing impairment. According to international guidelines, EHDI programmes aim to identify hearing impairment within one month of birth, diagnose by three months, and provide intervention to children with hearing impairment (as well as those at risk of hearing impairment) by six months of age to ensure they develop and achieve in line with their hearing peers

A retrospective review of the audiological management of children with hearing impairment, conducted at three public sector hospitals in Gauteng, found that the average age of diagnosis of hearing impairment is 23.65 months. Enrolment into an EI programme occurs at an average age of two years and five months. Similar findings were reported in the Western Cape and Free State. Delays in meeting the stipulated EHDI timeframes have been attributed to administrative challenges (such as procurement delays), lack of human resources, the busy schedules of speech-language therapists and audiologists in the public healthcare sector, and a lack of NHS services.

Hearing screening that coincides with clinic schedules for infant immunisation, as recommended by the HPCSA (2018), is thus strategic in achieving high screening coverage. Second, assets should include generalised documentation pertaining to infant record keeping. Electronic databases are already in place in certain regions. DoH policies advocate for accountable infant record documentation, especially with respect to otitis media

Additionally, acceptable continuity of care should be facilitated by adequate resources for referrals. The capacity to refer infants for diagnosis and intervention appears to be generally satisfactory in provinces such as Gauteng and North West, and the authors said, hearing impairment diagnosis by four months of age with intervention by eight months, as promulgated by the HPCSA (2007, 2018), appears practicable, dependent upon demand versus capacity at secondary and tertiary facilities.

It is also recommended that information about hearing impairment could be incorporated into existing caregiver health education programmes, like the Vitamin A supplementation programme. The importance of engaging and involving caregivers as key stakeholders in EHDI programmes is also highlighted.

In terms of barriers at PHC immunisation clinics, a lack of funding may underpin logistical issues regarding the identification of hearing impairment. Hearing screening in the South African context can be improved by addressing factors like lack of specialised hearing screening equipment, and, to help overcome some of the barriers regarding the recording of hearing results, training and assigning dedicated screening staff to the immunisation clinics as a possible solution. By so doing, hearing screening competency through experience can be improved and false positives and high refer rates reduced. Dedicated hearing screening staff can also relieve already over-burdened PHC staff, who may prioritise conditions such as HIV/Aids and TB.

Moreover, a screening coordinator can facilitate higher return rates through caregiver telephonic appointment reminders and visual rescreen reminders, facilitating consistent record keeping and using tele-audiology.

A significant quota of hearing-impaired children in South Africa will continue to have their rights denied until EHDI is incorporated as a cohesive, systematic and comprehensive nationalised healthcare strategy that is contextually responsive and relevant, say the authors. Healthcare practitioners bear the ethical responsibility to facilitate the realisation of the rights of the hearing-impaired to actualise their potential through EHDI.

In the South African context, current evidence supports the MOU three-day assessment clinic as the most accessible and efficient context for hearing screening programme implementation. However, it suggests consideration of a two-tiered approach involving early hearing screening of high-risk babies in the hospital setting, with screening of well babies at clinic level.

There should be continued reassessment of the South African contexts for hearing screening and the associated assets and barriers regarding practicability and efficiency. Although other healthcare contexts such as in-hospital clinics and PHC clinics, demonstrate potential for viable hearing screening settings, barriers to successful NHS programme implementation must be addressed before hearing screening can be efficiently implemented in the healthcare landscape.

Early Detection and Intervention in Audiology: An African Perspective

See also from the MedicalBrief archives:

Involvement of audiologists important in ototoxicity monitoring

A silent crisis: Hearing outcomes in children with meningitis