In 1972, a researcher in a small city in New Zealand set out to track the development of more than 1,000 new-born babies and their health and behaviour at age three, not realising then that over the next 50 years, the research would morph into one of the worldʼs most important longitudinal studies.

As children, participants in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Study, commonly known as “the Dunedin Study", were assessed every two years, then as adults every five to seven years.

The research into their life stories is still providing incredible insights into mental health, oral health, addiction and much more.

More than 1,400 peer-reviewed scientific journal articles, books and reports have been published by the research team.

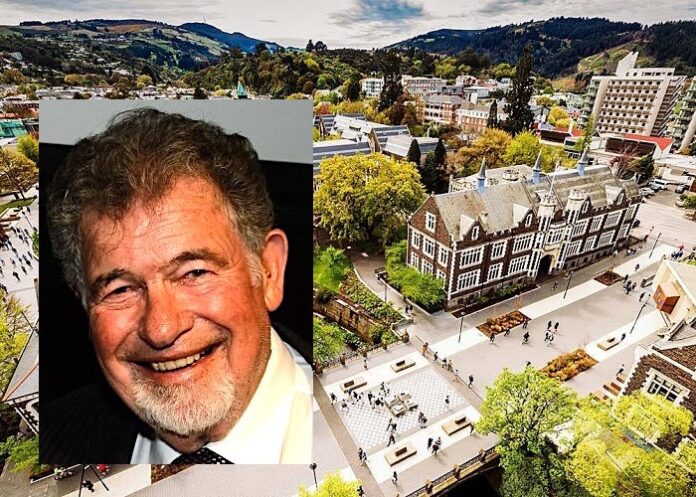

Yet despite the Study’s contribution to science, it is at its heart a very human story, says its director, psychologist Richie Poulton.

“I mean, 1,037 babies born 50 years ago have committed from that point on to giving themselves up to us to [be asked] 1,000 different questions, quite intrusive questions and to be poked and prodded every so many years so that they can essentially help others. That’s their main motivation,” he told Radio New Zealand (RNZ).

“That’s why they’ve contributed so much. And from our point of view, as researchers, we’re very human too, we’re not labcoat people who are indifferent and aloof, we have a very special relationship with our study members based on trust, and you don’t get trust or achieve that level of trust unless you are very real, very authentic.”

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the Study.

It does have some limitations from a domestic perspective – the cohort is reflective of 1970s Dunedin and not the more ethnically diverse New Zealand of 2022 – but it captures a group of people who have grown up in all sorts of households.

Founded by Dr Phil Silva in 1972, and now under the directorship of Prof Poulton, the Study continues with just under 1,000 members, who remain completely anonymous to everyone except the researchers, and all of whom turn 50 over the next year.

Every few years, since the members were born, they have returned to the University of Otago research centre, in Dunedin, flying in from all over the world to spend a few days having their mental and physical health thoroughly examined. Everything, from dental to cardiovascular health, from sexual behaviour to relationships and lifestyle, is covered.

“It’s incredibly important that we acknowledge the real heroes of the study, who are the study members. They do it for one main reason only, which is, they think it might help other people,” says Poulton, who joined the team in 1985.

The Guardian reports that at that stage, the study members were becoming teenagers and the work led then by Prof Terrie Moffitt would evolve into a paper on antisocial behaviour in adolescents – a body of research that has become the most cited theory in criminology.

Speaking from her home in North Carolina, Moffitt says: “So many countries use that 1993 paper as a justification for reforming their juvenile justice system to be less punitive and more supportive to young offenders.”

The data have also helped show that child maltreatment can lead to systematically higher levels of body-wide inflammation and an elevated risk of depression, Poulton says. “Inflammation is a marker of risk for all sorts of other physical diseases.”

“Children exposed to adverse psychosocial experiences have enduring emotional, immune, and metabolic abnormalities that contribute to explaining their elevated risk for age-related disease,” the paper reads.

As the years evolved, so too did the expertise the researchers needed to keep up with their membersʼ new life stages.

“When they were teenagers, it was drugs and alcohol and risky sex and law breaking. We had to become experts in that, but then they grew out of it. Then we had to become expert in how they pick a partner, how they decide to have children and when to have their first baby. Now that they’re going to be in their 50s, we’re studying how they’re preparing for old age,” says Moffitt, who is still an associate director.

The research will also shift to reflect changes in society, including delving into the thorny area of social cohesion, or, what makes communities and societies stick together, and why, all over the globe, they are becoming unstuck.

‘The best study of our type in the world’

“We thought, well, hold on, we’ve got a whole bunch of information on just about everything but we haven’t got a good measure of social cohesion yet,” Poulton says.

With that in mind, the team will now develop a method for understanding what underpins socially cohesive behaviour.

In a stroke of fortunate timing, the last assessment was taken in 2019 – just before the pandemic hit. But not wanting to miss an opportunity, the team contacted the members in 2021, to interview them about their experience of the pandemic and their plans for getting the vaccine, with that data due to be released soon, Moffitt says.

There are three things that set the Dunedin Study apart from longer-running studies around the world, Poulton says: a high retention rate (94% of the original cohort have stayed), a multidisciplinary approach that gathers an “incredible” breadth of information, and testing and interviewing people face-to-face rather than through questionnaires.

“That’s a very rare combo – the Holy Trinity in my mind – to make us the best study of our type in the world.”

Poulton adds that they guard the anonymity of the participants fiercely.

“We ask people incredibly intimate details of their life. And there’s an ironclad bond between ourselves and them not to divulge any information about them under any circumstances. I’m notoriously difficult on this particular point, I’ve had press people over the years harangue me about it.”

A Time magazine reporter once tracked down some of the participants, he told RNZ. “He stood on a street corner downtown and asked everyone at that point – if they looked 21 years old – whether they were in the study. He identified a couple of people, did a terrible character assassination of one poor person who had lived a hard life. And that’s hurt them forever.”

The information Dunedin Study participants divulge is deeply personal, Poulton says. “There’s not an assessment that goes past without some study members telling me when I meet them that they’ve told our interviewers something that they’ve never told another living human being, including their spouses.

“So, it’s a very deep study. And it relies upon that really sacred bond of trust between ourselves and in the study members.”

Over 50 years, some of the Study cohort have died and those losses are felt keenly, he says. “It feels like an extended family, in a way, and we feel the grief, it’s palpable.”

In 37 years of working on the study, Poulton has glimpsed many insights into the human condition.

“I know from this work just how precarious life is for so many of us. We all like to present ourselves to the world in the best possible light, it's natural. And so, you see people walking around doing their business going about their life and looking pretty good and feeling pretty good and things seem pretty on the up. In fact, they’re just hanging on by the skin of their teeth.

“So I’ve formed a view, a very basic kind of insight, which is, to be human is to be vulnerable. And I really get annoyed with people who shy away from vulnerability in terms of public rhetoric and stigmatise it and the like.

“Most of us at some point in our life hit a low ebb, and that’s natural, that’s normal. And we should not be ashamed, we should be able to seek help talk about it, be open about it. That’s what life is like. It’s not a cakewalk.”

This is what makes the cohort’s determination to keep helping the study so admirable, Poulton told RNZ.

“When you think about the tough life some of them have been leading, and have led for a long, long time, they get up in the morning, dust themselves off and front the world.

“And when we asked them every so often to come back and put up with us for a day and a half, they do it willingly. And they do it with good humour and grace and great courage.”

Radio New Zealand article – 50 years old: the Dunedin Study's amazing life-span (Open access)

The Dunedin Study (Open access)

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Long-lasting mental health is 'not normal' – New Zealand study

Brain structure differences link to individuals with lifelong antisocial behaviour

Slow walkers at age 45 have older brains and bodies