Gone are the days when most people instinctively trusted medical doctors – whom they looked up to as omniscient characters with power over life and death. The digital era has eroded that trust, with online medical and other health ‘influencers’ revolutionising how people access medical and health information and blurring the lines between medicine and marketing.

These influencers make millions – multimillions, in some cases – through their activities on Facebook, X, YouTube, LinkedIn, TikTok and Instagram, leveraging their qualifications in lucrative product endorsements, brand partnerships and media projects, writes Marika Sboros in Business Day.

They make it harder than ever for ordinary mortals to know who to trust for independent medical and well-being advice. Many people lack the expertise to assess influencers’ claims, making them especially vulnerable to persuasion by celebrity doctors and scientists.

By presenting information and advice in quick, digestible formats, influencers may also unintentionally encourage followers to self-diagnose or self-treat, with disastrous outcomes.

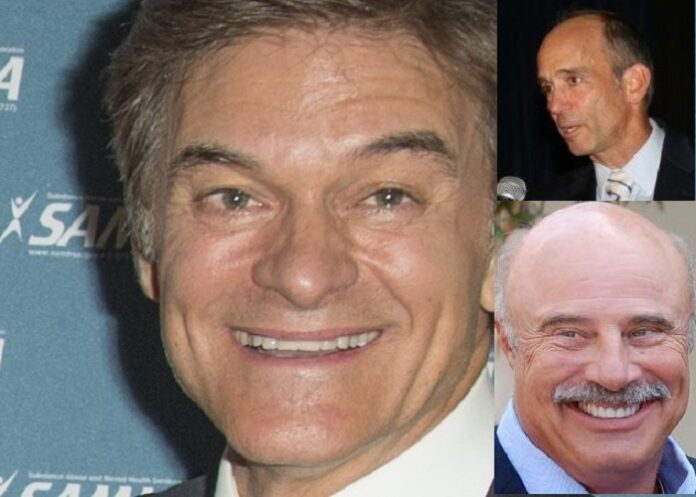

Among well-known influencers globally are Dr Mehmet Oz, Dr Phil McGraw, Dr Joseph Mercola, and relative newcomers Dr Peter Attia and Dr Andrew Huberman. They are case studies in the good, the bad and the ugly of influencers in the digital age. All are American – which isn’t surprising, since the rise of medical and scientific influencers is largely a US phenomenon.

The phenomenon predates social media. It is rooted in the unique blend of factors in US healthcare and media landscapes, where commercial partnerships, social media and a highly privatised health and wellness industry converge. The phenomenon is also a function of heavily commercialised healthcare and wellness sectors.

It creates a fertile market for doctors and scientists to transition seamlessly into entrepreneurial roles, and make oodles of boodle.

In the US, health influencers leverage and monetise their expertise in ways less commonly seen in other countries. They face sustained criticism for ethical contraventions and a lack of transparency about blatant conflicts of interest. They raise questions about whether they are merely being entrepreneurial or undermining their professional integrity – or both.

The most successful influencers no longer see patients in clinical practice, being too busy leveraging lucrative ventures and the subsequent profits.

Oz vies with Mercola as the most egregious example of the dangers of medical and health influencers. Along with McGraw, Oz and Mercola have net worths dwarfing those of Attia and Huberman. But then they have been at the influencer game much longer.

Oz is a cardiothoracic surgeon with a net worth estimated at more than $100m. He rose to fame after appearing on The Oprah Winfrey Show in 2004, followed by his own TV show, The Dr Oz Show. His focus quickly shifted almost exclusively from an active surgical career to media and product promotion.

He has popularised a “holistic” approach to medicine, health and well-being in body and mind outside the field of cardiothoracic surgery. Oz has regularly endorsed supplements, health products and therapies lacking robust science.

His promotion of “miracle” weight loss supplements, like green coffee extract and raspberry ketones, led to a Senate hearing in 2014. At the hearing, Oz admitted some of his endorsements lacked rigorous science, but dismissed ethical concerns, saying he just wanted to empower consumers with hope.

Writers in The New Yorker and The New York Times have criticised Oz for giving people false hope and promoting unscientific “miracle cures”. He has also promoted “energy medicine”, earning him the James Randi Foundation’s “Pigasus Award” in 2011 for achievements in pseudoscience.

He has given airtime to an Italian doctor who claimed cancer was a fungus treatable with baking soda. He has also given credence to communicating with the dead.

A 2014 study in The BMJ found that around half of Oz’s recommendations had minimal scientific evidence. In 2015, a group of 10 prominent physicians publicly urged Columbia University to dismiss Oz from his faculty position, citing “egregious lack of integrity” in promoting quackery. Columbia chose not to terminate his position.

Oz is unrepentant. His online presence remains strong, despite moving away from his TV show to collaborations with brands and social causes.

Mercola is an osteopathic medical physician with a net worth also estimated at more than $100m. In the US healthcare system, osteopathic and conventional medical doctors have the same professional standing.

Mercola’s income derives mostly from his eponymous online store selling supplements, wellness products and other items, book sales and speaking appearances.

His website is one of the most popular alternative-health sites, receiving about 1.9m unique visitors monthly.

Critics call him out for a business approach blending general health advice with pseudoscientific claims. He has faced repeated regulatory action in the US for deceptive marketing practices and selling unapproved products, including for cancer.

In 2016, Mercola agreed to refund $2.59m to customers after making false claims about health benefits of tanning beds.

During the pandemic, Mercola was listed among the “Disinformation Dozen”, a group of 12 people responsible for an estimated 65% of anti-vaccine content online.

Canadian academics at McGill University have called him a “doctor at war with medicine”. On the university’s website, they describe Mercola’s take on the vaccines during the pandemic as “a lucrative, conspiratorial fever dream”.

Mercola takes support for conspiracy theories to new heights. He suggested the pandemic was “anything but accidental”, promoting the idea of a “cabal of global health and economic elites” exploiting the pandemic for their own gain. This aligns with broader conspiracy theories about shadowy global powers controlling world events.

McGraw is the leader of the pack of multimillionaire health influencers, with an estimated net worth of $460m. Known simply as Dr Phil, he built wealth through his long-running, eponymous TV talk show since 2002, endorsements, books and other ventures.

He is not a medical doctor but doesn’t seem to mind if followers think he is. McGraw holds a PhD in psychology but hasn’t been licensed to practise in Texas or any other US state since 2006. He offers advice on mental health issues unbound by the ethical standards that licensed professionals must follow.

Critics say he reduces complex psychological and behavioural issues to simplistic solutions – creating misleading impressions about mental health treatments and recovery.

Attia and Huberman can seem like breaths of fresh air in stuffy, conspiracy-loving influencer circles. They have detractors even as both are transparent about their conflicts of interest.

Attia, a medical doctor who trained as a surgeon, has a net worth of between $3m and $8m. His income derives from medical practice, online content, consulting and partnerships with health and wellness brands.

He is generally respected within the US medical community in fields related to preventive health, longevity and metabolic science. He has built his reputation on a blend of rigorous medical training, practical experience and deep dives into cutting-edge scientific research on ageing and chronic disease.

Attia’s entrepreneurial ventures reflect a focus on lifestyle and wellness optimisation, distinguishing him as a figure in the lucrative health influencer economy. His podcast, The Peter Attia Drive, and appearances on health and science media platforms have brought high-level transparency to discussions about health and reliability of scientific literature.

Attia has a nuanced approach to controversial topics, such as fasting and ketogenic diets, which he advocates but tempers with evidence-based perspectives.

However, he also no longer practises clinical medicine in the traditional sense, having shifted focus to so-called “concierge medicine”.

Attia’s private practice, Attia Medical, caters to high net worth clients seeking personalised health-optimisation services. The business reportedly charges clients substantial fees, sometimes more than $150 000 year.

Critics say his methods and emphasis on extensive testing and personalised medicine create potential for inequality in health outcomes as they are largely accessible only to those with significant financial resources.

Attia is also an adviser or investor in health-related companies such as Dexcom, Athletic Greens and Oura Health. His ties with commercial ventures, notably the Oura Ring, have drawn scrutiny.

In 2023, Attia sued Oura Health for allegedly owing him $1.3m in unpaid stock options for promotional work on their product. The case is still pending. It is likely to provide further insights into the financial arrangements between health influencers and companies they promote.

Huberman is a tenured neuroscience professor at Stanford University. There is no current estimate of his wealth, which comes from a combination of academic salary and entrepreneurial ventures.

His reach and research make him notable in both academic and public spaces. However, Huberman’s blend of credible expertise with brand partnerships raises concerns about the potential effect of financial incentives on his objectivity.

His popular podcast, The Huberman Lab, has boosted his income through sponsorship deals, advertising revenue and merchandise sales. He has partnered with wellness brands, including Athletic Greens and Momentous.

Huberman co-founded the Neurohacker Collective, a company that develops cognitive-enhancing supplements. He continues his academic research with income and influence largely stemming from his online presence, with endorsements interwoven with scientific discussions.

Critics argue that Huberman’s transition into wellness topics, often outside his core expertise, creates an over-reliance on preliminary or unproven science and “biohacking” narratives. Huberman’s recommendations frequently involve supplements and lifestyle adjustments based on selective evidence.

Many influencers grow rich while creating crises for medical and health professions with endorsements and partnerships that have far-reaching effects on individual and public health globally.

BusinessLIVE article – Medical influencers come with serious side-effects (Open access)

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

TikTok main source of health info for Gen Z, finds survey

Dr Pimple Popper: It’s medicine, but not as we know it, Jim…

Legality of using social media influencers to promote e-cigarettes

Mythical, misleading detox wellness claims are fooling millions

Fake news and celebrity fads ‘put lives at risk’ — joint editorial

More than 25% of YouTube videos on COVID-19 contain misinformation