Sidelined in the European Union, never approved in the United States, dumped by South Africa, and now barely used in the United Kingdom, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is a medical success story turned sour.

Fergus Walsh, medical editor for the BBC, notes that the vaccine, hailed at the time as a triumph for British science, is “highly likely to have saved more lives [in the UK] to date than the Pfizer and Moderna jabs combined”. Nearly half of the UK adult population has received two doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine. Yet it is now barely used by the National Health Service (NHS) – of the more than 37m people who received a booster dose in the UK, just 48,000 of those were AstraZeneca.

Did politics and national interests got in the way of ambitions for the vaccine? Sir John Bell, Regius professor at Oxford University and at the heart of the team that created the vaccine, is highly critical about EU decision-makers.

“They have damaged the reputation of the vaccine in a way that echoes around the rest of the world,” he said. “Bad behaviour from scientists and politicians has probably killed hundreds of thousands of people.”

In early 2021, the Alpha variant was driving up COVID hospital admissions and deaths. However, Britain had begun to roll out the highly effective Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines, which it had approved here before anywhere else in the world.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca jab was celebrated as a homegrown success story, reflecting the strength of UK biosciences and academia. The government had even considered putting the union flag on the side of the vaccine. But the Oxford scientists were uncomfortable with any hint of trumpeting Britishness.

“There was too much nationalism,” says Prof Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute in Oxford, where the vaccine was developed. “It was encouraging competition between vaccine types, between countries. That’s the last thing you want in trying to control the pandemic and provide vaccines for the world.”

The vaccine’s approval in the UK coincided with Britain’s formal separation from the EU.

“What we couldn’t understand is that while we were deprived of vaccines, we heard that the UK was vaccinating non-stop,” said Dr Veronique Trillet-Lenoir, of the European Parliament’s Vaccine Contact Group.

By late January, the EU, whose vaccine rollout was lagging behind the UK, finally appeared ready to approve AstraZeneca. But before European regulators made their decision, Germany decided it should not be given to those over 65. And in France, President Emmanuel Macron called the vaccine “quasi-ineffective” in the elderly. But just hours later, the European Medicines Agency approved the jab for adults of all ages.

Both Germany and France would reverse their decisions, but the reputation of the vaccine had been damaged. Some doctors in France had to throw away doses because nobody was turning up to get the jab.

So how could this have happened?

The AstraZeneca, or AZ for short, vaccine was approved in the UK and EU for older adults before firm evidence showing it protected them from COVID. The trials demonstrated it protected younger volunteers. But the older adults had been recruited later. Their blood samples showed the vaccine produced a very strong immune response to coronavirus, just as it did in younger volunteers.

So an assumption was made that it would protect the elderly just as well as younger people. This turned out to be correct. In the midst of a pandemic, with vaccines desperately needed, regulators decided to approve the jab for older adults, who were most at risk from COVID. But France and Germany were more cautious.

At the same time, AZ was becoming embroiled in a major row about supplies. Its COVID vaccine was being manufactured in both the UK and the EU.

Because the UK had been guaranteed priority in a deal agreed before the rest of Europe, the company says it was unable to send vaccines from British plants to supplement the EU stock. Meanwhile, one million doses had already gone to the UK from an EU plant.

At the height of the crisis, the European Commission threatened to halt vaccine exports to the UK unless Europe got its “fair share”.

But what sealed the vaccine’s poor reputation among many across Europe was the emergence in March of a link to rare blood clots. Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, Austria and Denmark were among many nations that suspended use of the vaccine.

The overall risk of blood clots is very low, estimated at one in 65,000 overall – but slightly higher in younger adults. When European regulators declared that the vaccine’s benefits outweighed its risks, most lifted their suspension, but put age restrictions on the vaccine.

In the UK public confidence in the vaccine remained high, even after the jab was restricted to over-40s because of the link to rare blood clots.

But when it came to deciding on booster doses in the UK, the clots issue and the simplicity of the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA jabs not being age-restricted, sealed the AZ vaccine’s fate. It is registered as a booster vaccine here, but it proved simpler to give most people Pfizer or Moderna, even though this was far more expensive. Since then, evidence has shown that mixing different types of vaccine may offer better protection.

Elsewhere in Europe many saw the AZ vaccine as either unsafe or inferior: it was seen as a budget option. But it had been designed to be cheap, to be available at low cost throughout the world. Unlike the mRNA vaccines it could be transported and stored at fridge temperature, making it easier to administer in remote regions.

AZ agreed to license global production and distribution of the jab, to be sold not-for-profit, for about £3 a dose, a fifth of the price of the Pfizer jab.

A key player in this deal was the Serum Institute in India, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer. It agreed to produce more than a billion doses for low- and middle-income countries. But when the devastating Delta wave of COVID struck India in spring 2021, its government blocked vaccines from leaving the country for more than six months, making a global shortage of vaccines even more acute.

“Once India shut that door…the sense was we are truly well and truly done for because at that point, that was the only hope,” said Dr Ayoade Alakija of the African Union Vaccine Delivery Alliance.

The difference between rich and poor countries was extreme. In September 2021, when the UK, US, France and others were starting to offer booster doses, just one in 100 people in low-income countries had been double-jabbed.

“By the time you got through the first half of 2021, enough doses have been manufactured that could have prevented almost all of the deaths in the second half of 2021 – if those doses had been targeted at older adults, those with health conditions and healthcare workers around the world,” Prof Andrew Pollard from the Oxford Vaccine Group told the BBC.

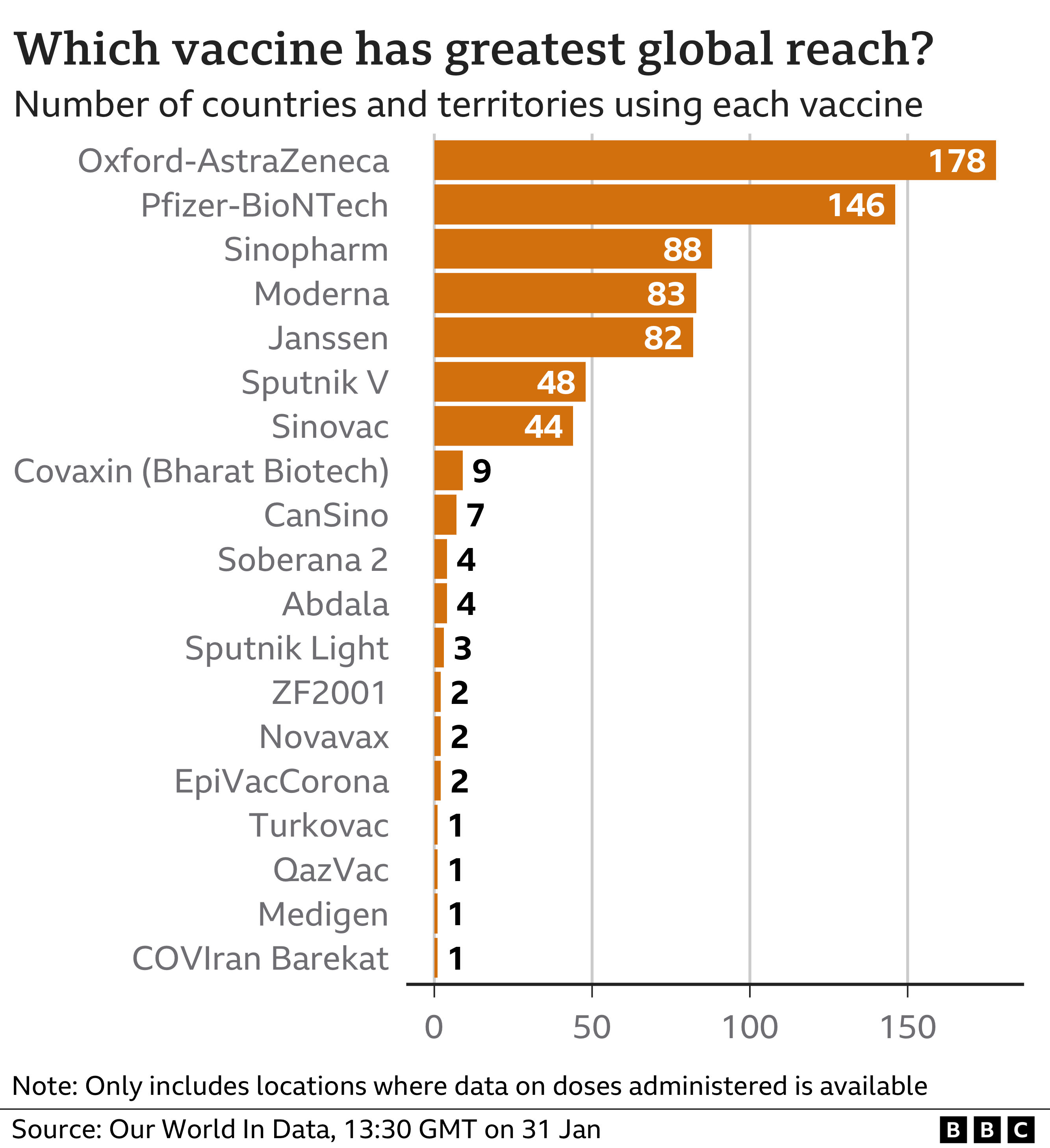

Despite all of the problems, more than 2,5bn doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab have been delivered to 183 nations, nearly two-thirds to low and middle-income countries. It will continue to be sold at cost to developing nations while the company says it will make a “modest profit” elsewhere. It is impossible to calculate how many lives have been saved by the vaccine, but the company estimates it to be more than a million.

More than a quarter of the 10bn doses of COVID jabs administered globally have been AstraZeneca, a vaccine created by a small team at a British university and sold at cost. Other COVID vaccines, by contrast, have created nine billionaires.

AstraZeneca: A Vaccine for the World? is a documentary aired this week on BBC Two.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Efficacy of Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine — Wits University trial

Two-dose vaccines induce lower antibodies against Omicron — Oxford study

Mixing COVID-19 vaccinations gives better immune response — Oxford trial

Cerebral venous thrombosis and the AstraZeneca vaccine — UK cohort study

Sale of AstraZeneca vaccines ‘resulted in up to 22,000 deaths’ of SA elderly