A smartphone app called Peek, which uses non-specialists in areas where eye specialists are scarce, is being rolled out across schools in Kenya. The government of Botswana is planning on using it nationwide and it is also being used in India.

For many years, Dr Andrew Bastawrous could not see clearly enough to spot the leaves on trees or the stars in the sky. BBC News reports that teachers kept telling him he was lazy and he kept missing the football during games. Then, aged 12, his mother took him to have his eyes tested and that changed everything.

Now he is a prize-winning ophthalmologist with a plan to use a smartphone app to bring better vision to millions of children around the world. Bastawrous is quoted in the report as saying: "I'll never forget that moment at the optometrist. I had trial lenses on and looked across the car park and saw the gravel on the road had so much detail I had had no idea about.

"A couple of weeks later I got my first pair of glasses and that's when I saw stars for first time, started doing well at school and it completely transformed my life."

The report says around the world 12m children, like Bastawrous, have sight problems that could be corrected by a pair of glasses. But in many areas, access to eye specialists is difficult – leaving children with visual impairments that can harm school work and, ultimately, their opportunities in later life.

In rural Kenya, for example, there is one eye doctor for 1m people. Meanwhile in the US, there is on average one ophthalmologist for every 15,800 people. In 2011 Bastawrous – by now an ophthalmologist in England – decided to study the eye health of the population of Kitale, Kenya, as part of his PhD. He took about £100,000 of eye equipment in an attempt to set up 100 temporary eye clinics but found this didn't work, as reliable roads and electricity were scarce.

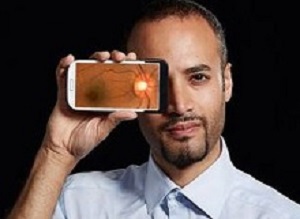

The report says it was realising that these same areas had great mobile phone coverage – with about 80% of the population owning a cell phone – that sparked the idea for Peek. Peek is a smartphone-based system that can bring eye care to people wherever they are. One part of the Peek system works in a similar way to an optician's eye chart, checking how well a person can see.

Bastawrous wanted to see if Peek could be used by non-specialists in areas where eye specialists are scarce. His team came up with the idea of training teachers – turning the teacher into an optician. Now a trial shows Peek can be used successfully to bring pocket eye tests to schools, helping more children to get the glasses they need.

The report says how it works is that children are shown a series of "E" shapes in different orientations and sizes. The child points in the direction the symbol is facing and the teacher (who cannot see the screen) then swipes the phone in the same direction

The app then determines how good the child's eyesight is.

Bastawrous – together with a team of researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine – spent a week training 25 teachers in 50 schools in rural Kenya to use their Peek system or standard eye tests normally done by specialist nurses. Half of the primary school children were then tested using the Peek system and half with standard eye tests using a series of paper testing cards.

After their tests, children who were examined by the Peek system were shown a split-screen simulation of how blurred their sight was compared with someone who could see clearly. Crucially, they were then given a printout of this to pass on to their parents, showing them just how poor their child's sight was.

The report says the Peek system also sent out details of the nearest eye clinic along with text-message reminders to encourage parents to take their children to hospital. Meanwhile, the children who took the paper-based vision test had their scores recorded manually and, if the teachers detected any eye problems, were given a paper letter to pass on to their parents.

Researchers found twice as many children attended hospital for free eye checks with Peek than went for standard eye tests.

Dr Hillary Rono, an ophthalmologist based in Kenya and lead researcher on the study, said: "This could be a world changer. To put it in perspective, I am one of the 100 ophthalmologists in Kenya. "I am in charge of a region that has 2m people. I cannot reach everybody in that area.

"Therefore, this technology will allow people without medical skills to identify the children with problems and link them with doctors like me so they can treat them."

The report says the study also found the app picked up on more children with eye problems than the standard tests – although, some were allergic conditions that temporarily blurred vision rather than sight problems that needed glasses.

Researchers realised these children benefited from treatment too so Peek has now been refined to spot the difference between eyesight issues and other eye problems and send children to the right place for help.

Commenting on the study, Peter Holland, of the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, said: "Innovations like Peek bring the costs of screening and referrals down and put services within reach of millions who are currently being left behind. They have the potential to offer the promise of sight to many who need it."

The report says Peek is being rolled out across more schools in Kenya, serving 300,000 children, with subsidised glasses for those who need them. The government of Botswana is planning on using it nationwide and it is also being used in India.

Summary

Background: Childhood visual impairment is a major public health concern that requires effective screening and early intervention. We investigated the effectiveness of Peek school eye health, a smartphone-based sight test and referral system (comprising Peek Acuity test, sight simulation referral cards, and short message service [SMS] reminders), versus standard care (Snellen's Tumbling-E card and written referral).

Methods: We initially compared the performance of both the Snellen Tumbling-E card and the Peek Acuity test to a standard backlit EDTRS LogMAR visual acuity test chart. We did a cluster randomised controlled trial to compare the Peek school eye health system with standard school screening care, delivered by school teachers. Schools in Trans Nzoia County, Kenya, were eligible if they did not have an active screening programme already in place. Schools were randomly allocated (1:1) to either the Peek school eye health screening and referral programmes (Peek group) or the standard care screening and referral programme (standard group). In both groups, teachers tested vision of children in years 1–8. Pupils with visual impairment (defined as vision less than 6/12 in either eye) were referred to hospital for treatment. Referred children from the standard group received a written hospital referral letter. Participants and their teachers in the Peek group were shown their simulated sight on a smartphone and given a printout of this simulation with the same hospital details as the standard referral letter to present to their parent or guardian. They also received regular SMS reminders to attend the hospital. The primary outcome was the proportion of referred children who reported to hospital within 8 weeks of referral. Primary analysis was by intention to treat, with the intervention effect estimated using odds ratios. This trial is registered with Pan African Clinical Trial Registry, number PACTR201503001049236.

Findings: Sensitivity was similar for the Peek test and the standard test (77% [95% CI 64·8–86·5] vs 75% [63·1–85·2]). Specificity was lower for the Peek test than the standard test (91% [95% CI 89·3–92·1] vs 97·4% [96·6-98·1]). Trial recruitment occurred between March 2, 2015, and March 13, 2015. Of the 295 eligible public primary schools in Trans Nzoia County, 50 schools were randomly selected and assigned to either the Peek group (n=25) or the standard group (n=25). 10 579 children were assessed for visual impairment in the Peek group and 10 284 children in the standard group. Visual impairment was identified in 531 (5%) of 10 579 children in the Peek group and 366 (4%) of 10 284 children in the standard care group. The proportion of pupils identified as having visual impairment who attended their hospital referral was significantly higher in the Peek group (285 [54%] of 531) than in the standard group (82 [22%] of 366; odds ratio 7·35 [95% CI 3·49–15·47]; p<0·0001).

Interpretation: The Peek school eye health system increased adherence to hospital referral for visual impairment assessment compared with the standard approach among school children. This indicates the potential of this technology package to improve uptake of services and provide real-time visibility of health service delivery to help target resources.

Authors

Hillary K Rono, Andrew Bastawrous, David Macleod, Emmanuel Wanjala, GianLuca DiTanna, Helen A Weiss, Matthew J Burton

[link url="https://www.bbc.com/news/health-44697342"]BBC News report[/link]

[link url="https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(18)30244-4/fulltext"]The Lancet Global Health abstract summary[/link]