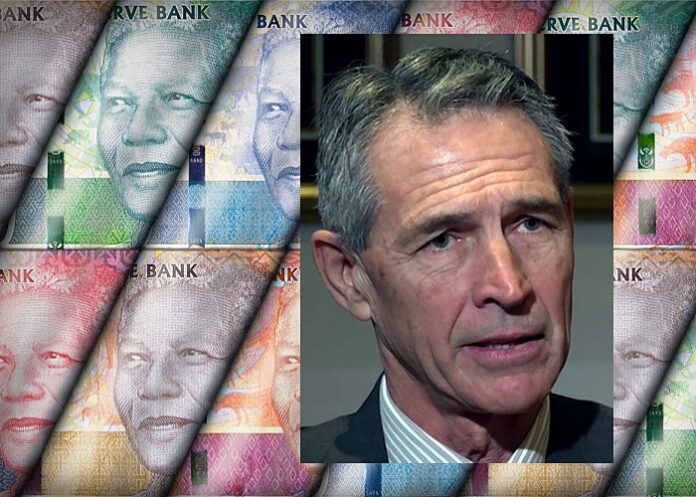

Much of the waste in SA’s healthcare expenditure is the fault of “unjustifiable private sector costs and gross public sector inefficiencies”, says Dr Nicholas Crisp, Department of Health Deputy Director-General. And Parliament will soon legislate to end the “mistaken belief” that people would be able to choose a medical scheme instead of the NHI, reports MedicalBrief.

Part of the problem, Crisp said at the Forbes Africa, Future of Healthcare cyber summit on 10 November, is that private sector patients took advantage of the system and so, too, did some practitioners, writes Chris Bateman for MedicalBrief. Crisp said that SA’s “slow burn” National Health Insurance, (NHI), would fundamentally change how the current 8,5% healthcare spend of South Africa’s total GDP is allocated, creating more equitable access and correcting a strong service bias towards upper income groups.

South Africa’s current 500bn annual healthcare spend, 8,5% of GDP, results in worse healthcare outcomes than its neighbouring countries – signalling that the money is being spent unwisely, with unjustifiable costs in the private sector and gross inefficiencies in the public sector. A single funder – the NHI – would simplify administration and procurement, which because of bulk purchasing will save billions, do away with the need for brokers and enable better healthcare outcomes for far more people, he added.

“The existing R500bn currently being spent is enough to fund the NHI. It’s what you spend it on that matters,” he said, rejecting mounting criticism that the NHI is unaffordable. Crisp added, “We can’t afford not to do it. We’re not getting value for money.

“Current unit costs in the private sector can be up to 10 times more for the unit cost for the same outcome in the public sector. So, it’s structural. The problem is that private sector patients take advantage of the system and so do some practitioners. There are structural reasons why the system is user-unfriendly.”

Crisp said the intention of NHI-enabling legislation was a “massive consolidation,” of the current 74 medical schemes down to just those that could top-up intended comprehensive NHI-funded services. Parliament would soon amend or do away with contested legal clauses that were causing confusion around medical schemes and leading to the mistaken belief that people could choose a medical scheme instead of the NHI.

“So instead of 50% of the money being spent through medical schemes on some 15% or 16% of the population, there’ll be a far smaller number of people insuring themselves privately through high-end medical aids for only a very few procedures not covered by the NHI fund,” he explained.

He added that fiscal prudence was paramount for South Africa to maintain its credibility with global partners and ratings agencies. Getting better value for money would entail first getting the primary healthcare space running smoothly and efficiently over the next three to five years before ramping up universal coverage over the next decade or two.

However, this did not mean spending up to 18% of GDP, as was happening in the United States. “We don’t want to emulate that. But we also don’t want to spend just 4,5% of GDP on the majority of the population. We need to spend the full 8,5% of GDP more wisely and equitably,” he stressed.

He said many critics backed the argument that the NHI would prove impossibly costly by dividing the beneficiaries of the private sector healthcare system and multiplying it out by SA’s 60m population – a ‘fallacious’ argument that failed to look at the country’s overall healthcare structure and its relative costs. There would be some transitional NHI set-up costs, but the overall running costs would be no more than what was currently the case.

Fair pricing, removing unnecessary administration and procurement costs and appropriate servicing made the NHI both “necessary and affordable”.

COVID paves the way

Asked whether the unprecedented level of co-operation between the public and private sector prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic was likely to continue, Crisp responded, “It will be our fault if it does not. I’ve been in the game since 1984 and there is no reason why we can’t collaborate. We may have different vested interests, but we are all colleagues looking after patients. It’s been my privilege to work with hospital practitioners and bed pricing, costing the COVID-19 vaccination rollout and finding solutions to obstacles. It’s been a pleasant experience, though we differ from time to time. I’d like to formalise and structure those engagements going forward,” he said.

An NHI would see one set of codes for medicines, products and services, removing a huge amount of costs and the current burden of a complex set of medical aid administrations.

With universal healthcare, all that would be needed was accreditation of providers with a central fund while the Office of Health Products Procurement would vastly simplify matters. The current Affordable Medicines Directorate would expand from the 150 currently listed drugs into the full formulary and spectrum of drugs.

All services provided would have to be accredited with proof of accreditation needed to make purchases.

“If managed properly this will all push prices down, but it takes time. We’re planning for 10 to 20 years from now – the first baby steps will be implemented next year, but I’ll be dead when it’s completed,” he chuckled.

Asked how the government planned to maintain and widen the accessibility of skills and prevent the healthcare worker burnout witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Crisp said the biggest challenge at present lay with the senior levels of staff and issues of how collective bargaining was conducted in the public sector. Occupational specific dispensation and senior salary levels would require a thorough audit on the kinds of specialist skills needed. The human resource structures were historically very rigid.

“We need to bring in technical specialists and recognise that we often don’t need directors and deputy directors. These new technical specialists will be paid more than chief and deputy directors and I’ve no problem with that – we need that kind of technical capability. We also need lawyers and actuaries, and we’ll have to outsource all that kind of work. There’s nothing stopping us from bringing in those skills. We’re already seeing fledgling improvements across the country and some provinces have made a lot of improvements. It’s not going to be easy, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have to do it.”

He acknowledged the burden that corruption had put on the healthcare system but said this had resulted in unprecedented safeguards being put in place.

This article is produced under Creative Commons licence and can be freely republished with acknowledgment to MedicalBrief and a link to this original.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

SAMA's warnings on NHI Bill met with hostility

DoH gives assurance that it will stop ‘acting as if NHI Bill is already law’

Solidarity launches PAIA application regarding NHI remarks by Dr Nicholas Crisp

Health committee’s new chair says technology will thwart NHI corruption