Increasing evidence has shown an association between the popular contraceptive injection depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (dMPA) – known as depo provera – and meningioma, leading to increasing media attention, and regulatory and legal proceedings.

Although the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) has issued a statement acknowledging the issue, the lack of local data makes it difficult to fully assess the implications in this country.

In the SA Medical Journal, a group of experts, led by a team from the University of Cape Town, discusses the association between dMPA and meningiomas in the South African context, providing a summary of the current data on risks, and suggesting how this should affect recommendations for the prescribing of dMPA from a public health perspective.

They also identify gaps in local data, and propose where efforts should be stepped up to inform a rational national contraceptive strategy

They write:

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (dMPA) remains a commonly used contraceptive worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, being frequently preferred due to its convenient three-monthly dosing, its efficacy and its discretion.

In South Africa, it is used by nearly a quarter of all women who are on contraception.

In the past two years, retrospective studies using large datasets from both Europe and the USA have shown an association between dMPA use and meningioma, with the strength of the association appearing to increase with prolonged dMPA use.

These findings led to class-action lawsuits against Pfizer, the largest manufacturer of dMPA, in some countries.

Since dMPA is the most widely used contraceptive among SA women, understanding any potential association with meningioma is particularly relevant locally.

However, despite widespread use here, there are no robust SA data exploring this association, limiting the ability to quantify the risk in women who use, or have previously used, dMPA, to guide evidence-based prescribing and counselling on safety of contraceptive choices.

Epidemiology of meningiomas

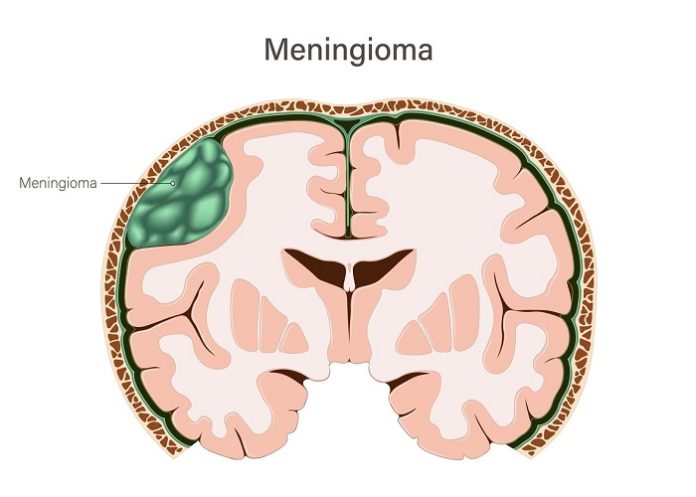

Meningiomas are the most common primary brain tumours in adults, with an age-adjusted incidence of 8-10 per 100 000 person-years.

Advancing age, obesity, neurofibromatosis and female sex are well-established risk factors, with incidence in women nearly double that in men. Advancing evidence from the USA also suggests ancestry mediates risk, with non-Hispanic black populations showing a higher incidence than non-Hispanic white populations.

Incidence and risk factors across Africa are limited. Small regional and single-centre retrospective studies in SA (with samples of between 48 and 505 patients) have confirmed meningiomas are the most common adult brain tumours locally, more common in women than men and among black women.

The anatomical location of meningiomas is clinically and biologically significant. Most arrive at convexity and parasagittal sites, with other common locations including the skull base, like the sphenoid ridge.

Tumour site influences presentation, surgical accessibility and prognosis. Molecular studies show that location corresponds to distinct genetic profiles.

Specifically, skull base tumours are often associated with TRAF7, PI3K and hedgehog pathway mutations, whereas convexity tumours more commonly harbour NF2 alterations.

Recent data also suggest differences in molecular subtypes across different demographic groups, with USA patients recorded as ‘black’ showing a higher prevalence of anterior skull base tumours, increased hedgehog pathway mutations and poorer progression-free survival despite similar extents of resection.

These findings highlight the need for further geographically and ethnically diverse studies to better understand meningioma biology.

Association between prolonged dMPA use and meningiomas

Exposure to progesterone is an important physiological factor implicated in meningioma development and growth. The link was first observed in relation to hormonal fluctuations during menstruation and pregnancy.

Subsequent studies found that benign meningiomas often express progesterone receptors, loss of which has been associated with more aggressive, infiltrative tumour behaviour.

The density of progesterone receptor expression appears to vary by tumour location, being higher in skull base tumours. Furthermore, exposure to progestins has been implicated in changing the molecular characteristics of meningiomas.

Given the importance of progesterone signalling in meningioma biology, there has been long-standing interest in the effects of exogenous progesterone exposure on this tumour growth.

Before 2024, evidence linking dMPA to meningiomas was limited.

The first case was in the UK in a man who had taken medroxydroprogesterone for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma, but developed an intracranial meningioma.

Subsequently, data came mainly from small retrospective case series and case-control studies from Indonesia, where the number of women who use dMPA as their preferred contraceptive method is similar to SA.

Notably, Dewata et al compared women with histologically confirmed meningiomas (cases) with similarly-aged women who had received brain imaging to exclude an intracranial meningioma (controls). They found women who had meningiomas were three times likelier to have used dMPA (155 of 212 meningioma cases, odds ratio (OR) 3.13, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.03 – 4.85), with the risk increasing with >15 years of dMPA exposure (OR 4.45, 95% CI 2.35 – 8.35).

As these data were drawn from single-centre case-control studies with limited generalisability and lacked the ability to quantify risk, they necessitated the subsequent development of pharmaco-epidemiological studies.

Since 2024, four large case-control studies exploring the association between dMPA and meningioma in the USA, France and Sweden have been published.

While all are consistent in their reporting of a significant association between dMPA and women having received a diagnosis of a meningioma, there are important methodological differences affecting how the results from each should be interpreted.

A French case control study of 18 892 women who had undergone surgical resection for a meningioma and 90 305 controls, matched on year of birth and area of residence, found those with meningioma had higher odds of having been exposed to dMPA, with OR 5.55 (95% CI 2.27 – 13.56).

A Swedish study of 1 055 women with a meningioma diagnosis in a cancer registry and 21 100 controls matched on year of birth and country of residence found a similar association between dMPA and meningiomas (OR 5.49, 95% CI 4.51 – 6.67).

A case control study from the USA on women with meningiomas identified through private health insurance records (i.e. not only those who underwent resective surgery), reported an OR of 1.53 (95% CI 1.40 – 1.67): 813 of 117 503 women with meningiomas exposed to dMPA (0.69%) v. 4 652 of 1 072 907 matched controls (0.43%).

A second case-control study by the same investigators also found a significant association between dMPA exposure and meningiomas in women from a smaller, publicly funded medical insurance scheme, using exposure to levonorgestrel or norethindrone as an active comparator (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.01 – 2.56).

While all of the case-control studies found that the association strengthened with longer dMPA exposure, only the US study by Griffin et al. confirmed that the association occurs exclusively in intracranial meningiomas, although it did not examine variation across different intracranial regions.

These studies demonstrate an association with dMPA exposure that strengthens with exposure duration, but cannot quantify incidence.

USA cohort study

A case control study from the US using electronic health records of 10 425 438 women was able to estimate meningioma incidence and relative risks with exposure to several contraceptives. The research compared women who had been exposed to dMPA with those without any exposure, and determined how many in each group developed meningiomas over the follow-up period.

Using propensity score matching, this study was able to adjust for many meningioma-relevant potential confounders including age, race, ethnicity, parity, other cancer diagnoses, neurofibromatosis, radiological procedures received and body mass index.

The incidence of meningioma was 7.39 per 100 000 patient-years in the dMPA group, and 3.05 per 100 000 patient-years in the control group (relative risk 2.43, 95% CI 1.77 – 3.33).

Based on those results, the number needed to harm is 1 152 (i.e. on average, for every 1 152 women who receive dMPA, there will be one additional case of meningioma relative to those who do not receive dMPA).

Furthermore, the authors calculated the attributable risk percentage, stating that in the patients with meningiomas, 59% were probably due to dMPA exposure.

While this study further supports the finding that prolonged dMPA exposure increases risk, unlike the previous US study, it did not stratify meningiomas by location.

Relevance to SA women and research gaps

While the association between dMPA and meningiomas is of international concern, factors that uniquely affect SA women need to be considered: 23% of SA women between 19 and 45 use injectable contraceptives.

By comparison, the percentages of women in France and the USA are 0.2% and 2.3%, respectively. dMPA therefore plays a greater role in SA’s contraceptive landscape than where most studies have been conducted.

To our knowledge, there are no published studies of the association between dMPA and meningioma in Africa.

There is also a paucity of data on meningioma epidemiology in SA, and how this might differ from the well-characterised international meningioma registries. In the public sector, data regarding contraceptive use are generally limited to household surveys.

Cohort studies with linked data on diagnoses and prescription would be valuable to describe patterns of contraceptive use, estimate incidence of and risk factors for meningiomas, and explore the association between dMPA and meningiomas in our setting.

However, sources of potential linked data are limited, and prospective data collection may be challenging.

Primary care family planning facilities do not currently keep electronic dispensing records, and use facility-based, paper-based systems, posing challenges in quantifying dMPA exposure and duration of exposure.

Such data, along with contraceptive exposure data, are essential in understanding how hormonal therapies affect the presentation of meningiomas.

Without accurate epidemiological data on intracranial meningiomas in SA, it is difficult to determine whether local patterns of dMPA use influence the types of meningiomas that develop, the anatomical locations in which they arise, or the severity of their presentation.

The risk of developing meningioma must be balanced with the need for effective contraception.

Over-estimating the risk could lead to unnecessary discontinuation of dMPA use, while under-estimating it may expose women to preventable disease. Locally generated data are needed to guide balanced and evidence-based decisions.

Suggestions for future policy

Well-designed national prospective studies are required, and would align with a greater need for robust registries for neuro-oncology within SA and the African continent.

Efforts to strengthen electronic data collection systems should also be encouraged.

Meanwhile, cross-discipline collective effort is needed to create guidelines for sex hormone therapies in patients with meningiomas, similar to those in other countries.

Conclusion

While prolonged dMPA use is associated with a small increased risk of meningioma, responses must remain evidence-based to protect women’s health, including safeguarding access to effective contraception.

Given that dMPA remains a preferred, practical option, discontinuing it without a clear rationale or contingency plan risks undermining the progress achieved by national family planning programmes.

Currently, there is no evidence that meningioma risk in SA users of dMPA is higher than in other countries : around 4m South African women rely on this method.

But while further research is needed, the association between dMPA exposure and meningioma cannot be ignored. We suggest the following recommendations:

(i) Inform women using dMPA about its possible link to meningioma, and advise that it should not be used for >two years unless other options are unsuitable.

(ii) Women on dMPA who develop headaches, vision changes or seizures should seek medical review promptly.

(iii) If a woman using dMPA is diagnosed with and/or has been treated for a meningioma, stop dMPA and advise alternative contraceptive methods.

(iv) Report all cases to the SA Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA)

(v) Document dMPA exposure in medical records, preferably electronically.

(vi) Ensure patients have access to a range of alternative safe, suitable contraception..

No evidence

While prolonged dMPA use is associated with a small increased risk of meningioma, there is no evidence that the incidence in SA users is higher than in other countries.

The absence of local epidemiological and pharmacovigilance data is a vulnerability so it is important to generate local evidence, strengthen surveillance, improve contraceptive record-keeping and establish clear clinical pathways for risk.

R J Burman,1,2 MB ChB, DPhil; R de Waal,3 MB ChB, MPH; K Cohen,4 MB ChB, MMed (Clin Pharm);M Blockman,4 MB ChB, MMed (Clin Pharm); M Patel,5 MB ChB, FCOG (SA); D Hockman,2,6 MSc, PhD;D M Fountain,7 MB BChir, MRCS; S Jeyaretna,8 BMBS, FRCS (SN); S Singh,9 MB ChB, FC Path (SA) Anat;H Mustak,10 MB ChB, FCOphth (SA); B De John,1,2 MB ChB, FC Neurosurg (SA); D Lubbe,2,11 MB ChB, FCORL (SA)

1Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, University of Cape Town; 2Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town; 3Centre for Integrated Data and Epidemiological Research, School of Public Health, University of Cape Town; 4Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town; 5Division of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Cape Town; 6Division of Cell Biology, Department of Human Biology, University of Cape Town; 7MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, UK; Division of Neurosurgery, Nuffield Department of Surgery, University of Oxford, UK; Division of Anatomical Pathology, Department of Pathology, University of Cape Town; 10Division of Ophthalmology, Department of Surgery, University of Cape Town; 11Division of Otolaryngology, Department of Surgery, University of Cape Town.

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

New warning added to contraceptive drug label as lawsuits rise

Birth control jab linked to higher brain tumour risks – large US analysis

SA women allege Pfizer knew about contraceptive tumour risk