Being overweight or underweight, as measured by the Body Mass Index, could knock four years off life expectancy, a five-year UK population cohort study of nearly 2m people found.

Being overweight or underweight, as measured by the Body Mass Index, could knock four years off life expectancy, a five-year UK population cohort study of nearly 2m people found.

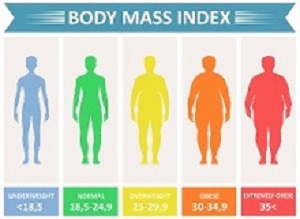

Researchers found that, from the age of 40, people at the higher end of the healthy Body Mass Index (BMI) range had the lowest risk of dying from disease. But people at the top and bottom ends of the BMI risked having shorter lives.

BMI is calculated by dividing an adult's weight by the square of their height. A "healthy" BMI score ranges from 18.5 to 25. According to the report, most doctors say it is the best method they have of working out whether someone is obese because it is accurate and simple to measure.

The study showed that life expectancy for obese men and women was 4.2 and 3.5 years shorter respectively than people in the entire healthy BMI weight range. The difference for underweight men and women was 4.3 (men) and 4.5 (women) years.

The report says BMI was associated with all causes of death categories, except transport-related accidents, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases. However, not everybody in the healthy category is at the lowest risk of disease, according to report author Dr Krishnan Bhaskaran at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

He is quoted in the report as saying: "For most causes of death we found that there was an 'optimal' BMI level, with risk of death increasing both below and above that level. At BMIs below 21, we observed more deaths from most causes, compared with the optimum BMI levels. However, this might partly reflect the fact that low body weight can be a marker of underlying ill-health. For most causes of death, the bigger the weight difference, the bigger the association we observed with mortality risk. So a weight difference of half a stone would make a relatively small (but real) difference; we could detect these small effects because this was a very large study."

Some experts have questioned whether BMI is an accurate way of analysing a person's health. However, the report says, Dr Katarina Kos, senior lecturer in diabetes and obesity at the University of Exeter, believes it is. "For the majority of people, BMI is a good measure."

Kos said the study did not contain any surprises but added that overweight people who could lower their BMI may reap the health benefits. "We know from the diabetes remission data how low-calorie diets and weight loss can improve diabetes, for example," she said. "And we know weight loss can also help in improving risk so that would also then improve mortality rates."

The study suggested that a higher BMI in older people may not be as dangerous, because a bit of extra weight was "protective" for them. But Kos, who worked on a study on this topic in 60 to 69-year-olds last year, disagreed with the findings. Her study on what is known as the obesity risk paradox, did not "support acceptance" of the theory.

Abstract 1

Background: BMI is known to be strongly associated with all-cause mortality, but few studies have been large enough to reliably examine associations between BMI and a comprehensive range of cause-specific mortality outcomes.

Methods: In this population-based cohort study, we used UK primary care data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) linked to national mortality registration data and fitted adjusted Cox regression models to examine associations between BMI and all-cause mortality, and between BMI and a comprehensive range of cause-specific mortality outcomes (recorded by International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [ICD-10] codes). We included all individuals with BMI data collected at age 16 years and older and with subsequent follow-up time available. Follow-up began at whichever was the latest of: start of CPRD research-standard follow up, the 5-year anniversary of the first BMI record, or on Jan 1, 1998 (start date for death registration data); follow-up ended at death or on March 8, 2016. Fully adjusted models were stratified by sex and adjusted for baseline age, smoking, alcohol use, diabetes, index of multiple deprivation, and calendar period. Models were fitted in both never-smokers only and the full study population. We also did an extensive range of sensitivity analyses. The expected age of death for men and women aged 40 years at baseline, by BMI category, was estimated from a Poisson model including BMI, age, and sex.

Findings: 3 632 674 people were included in the full study population; the following results are from the analysis of never-smokers, which comprised 1 969 648 people and 188 057 deaths. BMI had a J-shaped association with overall mortality; the estimated hazard ratio per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI was 0·81 (95% CI 0·80–0·82) below 25 kg/m2 and 1·21 (1·20–1·22) above this point. BMI was associated with all cause of death categories except for transport-related accidents, but the shape of the association varied. Most causes, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory diseases, had a J-shaped association with BMI, with lowest risk occurring in the range 21–25 kg/m2. For mental and behavioural, neurological, and accidental (non-transport-related) causes, BMI was inversely associated with mortality up to 24–27 kg/m2, with little association at higher BMIs; for deaths from self-harm or interpersonal violence, an inverse linear association was observed. Associations between BMI and mortality were stronger at younger ages than at older ages, and the BMI associated with lowest mortality risk was higher in older individuals than in younger individuals. Compared with individuals of healthy weight (BMI 18·5–24·9 kg/m2), life expectancy from age 40 years was 4·2 years shorter in obese (BMI ≥30·0 kg/m2) men and 3·5 years shorter in obese women, and 4·3 years shorter in underweight (BMI <18·5 kg/m2) men and 4·5 years shorter in underweight women. When smokers were included in analyses, results for most causes of death were broadly similar, although marginally stronger associations were seen among people with lower BMI, suggesting slight residual confounding by smoking.

Interpretation: BMI had J-shaped associations with overall mortality and most specific causes of death; for mental and behavioural, neurological, and external causes, lower BMI was associated with increased mortality risk.

Authors

Krishnan Bhaskaran, Isabel dos-Santos-Silva, David A Leon, Ian J Douglas, Liam Smeeth

Abstract 2

Background: For older groups, being overweight [body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2): 25 to <30] is reportedly associated with a lower or similar risk of mortality than being normal weight (BMI: 18.5 to <25). However, this “risk paradox” is partly explained by smoking and disease-associated weight loss. This paradox may also arise from BMI failing to measure fat redistribution to a centralized position in later life.

Objective: This study aimed to estimate associations between combined measurements of BMI and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) with mortality and incident coronary artery disease (CAD).

Design: This study followed 130,473 UK Biobank participants aged 60–69 y (baseline 2006–2010) for ≤8.3 y (n = 2974 deaths). Current smokers and individuals with recent or disease-associated (e.g., from dementia, heart failure, or cancer) weight loss were excluded, yielding a “healthier agers” group. Survival models were adjusted for age, sex, alcohol intake, smoking history, and educational attainment. Population and sex-specific lower and higher WHR tertiles were <0.91 and ≥0.96 for men and <0.79 and ≥0.85 for women, respectively.

Results: Ignoring WHR, the risk of mortality for overweight subjects was similar to that for normal-weight subjects (HR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.19; P = 0.066). However, among normal-weight subjects, mortality increased for those with a higher WHR (HR: 1.33; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.65) compared with a lower WHR. Being overweight with a higher WHR was associated with substantial excess mortality (HR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.25, 1.61) and greatly increased CAD incidence (sub-HR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.39, 1.93) compared with being normal weight with a lower WHR. There was no interaction between physical activity and BMI plus WHR groups with respect to mortality.

Conclusions: For healthier agers (i.e., nonsmokers without disease-associated weight loss), having central adiposity and a BMI corresponding to normal weight or overweight is associated with substantial excess mortality. The claimed BMI-defined overweight risk paradox may result in part from failing to account for central adiposity, rather than reflecting a protective physiologic effect of higher body-fat content in later life.

Authors

Kirsty Bowman, Janice L Atkins, João Delgado, Katarina Kos, George A Kuchel, Alessandro Ble, Luigi Ferrucci, David Melzer

[link url="https://www.bbc.com/news/health-46031332"]BBC News report[/link]

[link url="https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(18)30288-2/fulltext"]The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology abstract[/link]

[link url="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5486197/"]The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition abstract[/link]