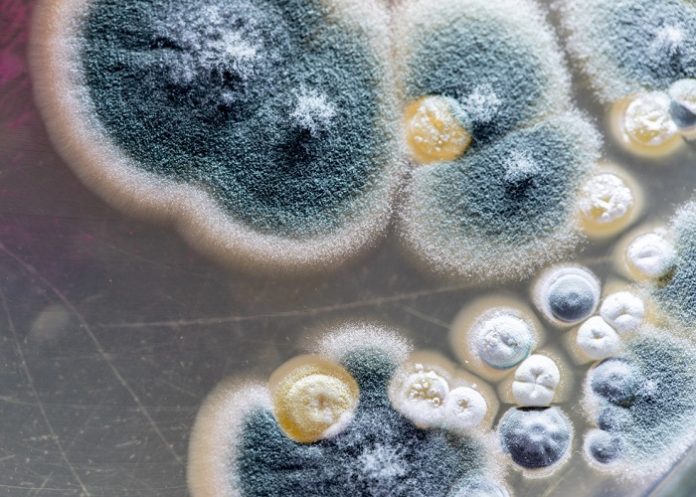

A new superbug threat is spreading around the world. The culprit: microscopic fungal spores that live in and on human bodies and in the dirt and air.

And the bad news is, they are everywhere. American Torrence Irvin, for instance, believes the life-threatening fungi called Coccidioides entered his lungs in June 2018 while he was relaxing in his backyard in California.

“I was enjoying a nice summer day, playing games on my phone and having a cocktail,” said Irvin, who came close to death before a specialist correctly diagnosed his infection nearly a year later.

“I went from a 130kg man to a 68kg skeleton,” he said. “It came to the point where my first doctors told my wife there was nothing we can do.”

Like Irvin, Rob Purdie was in his California home, working in his garden, when, he believes, he inhaled Coccidioides spores in 2012.

CNN reports that the infection soon spread to his brain, causing fungal meningitis. The condition is marked by potentially deadly inflammation of the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

“In about 3% of people that are infected, the fungus goes somewhere else in the body, beyond the lungs to your skin, bone and joints, and other organs, or weird places like your eyeball, tooth and pinkie finger,” said Purdie, a founding member of the non-profit organisation MYCare – or MYcology Advocacy, Research & Education – which educates and promotes research in the field of fungal diseases.

“Half the time it goes to the brain, like mine,” Purdie said. “To control my disease for the rest of my life, I have to take intracranial injections with a toxic 80-year-old drug that is slowly poisoning me.”

Recent global estimates indicate there are 6.5m invasive fungal infections and some 3.8m deaths annually – and some of those infections are becoming more difficult to treat.

Due to the emerging microbial resistance to all existing fungicidal drugs, in April the World Health Organisation listed 19 fungal species as critical, high or medium priority for new drug development.

Fungi in the genus Coccidioides are on WHO’s priority list.

While deaths associated with bacterial superbugs are higher than those linked with fungi, (4.7m vs. 3.8m), there are hundreds of antibiotics available to treat bacteria. In contrast, only about 17 antifungal drugs are in use, says the US Centres of Disease Control and Prevention.

One reason is because of the difficulty in making drugs that kill the fungus without hurting humans.

“Genetically, fungi are more closely related to humans than to bacteria,” said infectious disease specialist Dr Neil Clancy, an associate professor of medicine and director of the mycology programme at the University of Pittsburgh.

“If you’re trying to make an antifungal drug, you’ve got to come up with targets that won’t harm genes and proteins humans have. Right now, the drug we use that kills fungus best cross-reacts with human kidney cells, so you can end up with kidney failure.”

Other antifungals can cause impotence, pancreatitis, liver damage and severe allergic reactions.

Fungal infections in otherwise healthy people are typically resolved with current antifungal treatment, especially when caught early, specialists say.

Those most vulnerable to invasive fungal infections are people with weakened immune systems, perhaps due to chemotherapy, dialysis, HIV/Aids, immunosuppressant medications, and organ or stem cell transplants.

Yet neither Irvin or Purdie was immunocompromised when they contracted coccidioidomycosis, or cocci, the disease caused by the fungi they inhaled.

Because researchers first identified cocci in California’s San Joaquin Valley, it’s also known as valley fever.

“Some of these patients, despite not being immunosuppressed, just don’t fight off the infection well,” said fungi researcher Dr George Thompson, a Professor of Medicine at the University of California-Davis School of Medicine.

“If we could figure out what’s different about their immune system, perhaps we can augment it to help them counter the fungus,” said Thompson, the specialist who diagnosed Irvin with valley fever.

The most dangerous resistant fungi

Cryptococcus neoformans, which causes a potentially deadly form of meningitis, topped WHO’s list of the four fungal parasites that are most critical priority for research and new drug development. The death rate from an infection with C. neoformans is extremely high, up to 61%, especially in patients with HIV infections.

Aspergillus fumigatus, a mould that damages the lungs and can spread to other parts of the body, was second on the list.

“Aspergillus is everywhere — your soil, in the leaves you rake, in the mulch you put down,” Thompson said. “It’s hard to avoid and has a very high associated mortality rate, about 40% in some people, so that’s an infection for which we desperately need new drugs.”

Candida auris is third on the critical list and unique in several ways. First, the microbe was already resistant to all four classes of fungicidal treatments when it first appeared in the United States in 2013.

“Candida auris arrived with antifungal resistance baked in,” said Pitt’s Clancy. “It doesn’t require the emergence of new mutations to develop antifungal resistance.”

Also known as C. auris, the yeast is unusual because it’s “sticky”, adhering to both plastic and skin in ways that other Candida species don’t, said fungal researcher Dr Jatin Vyas, a Professor of medicine at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City.

This fungal tenaciousness makes C. auris extremely difficult to decontaminate when found in busy hospitals, nursing homes and dialysis clinics.

“A patient can be colonised with C. auris, then a healthcare worker or someone who’s caring for them touches them and gets the organism,” Vyas said. “The caregivers can then be colonised and pass it from patient to patient.”

In 2016, there were 51 clinical cases of C. auris in four states. By 2023, a total of 4 514 clinical cases had been identified in 36 states. Clinical cases of the multidrug-resistant yeast rose by 95% year-over-year in 2021 alone.

Candida albicans, a cousin of C. auris, is a common yeast that lives in small amounts on the skin and in the mouth, throat, intestines and vagina. C. albicans is fourth on the list of WHO’s critical priority pathogens.

As part of a healthy microbiome, it lives peacefully in the body and may even play a role in boosting immunity. When that balance is disrupted by antibiotics or an immunosuppressant, however, it can cause troubling yeast infections or lead to antimicrobial-resistant invasive candidiasis.

“Candida infections can end up in the bloodstream, and when they do, the mortality rates in the literature range anywhere from 40% to 60%, even with prompt diagnosis and treatment,” Vyas said.

For decades, cocci was primarily diagnosed in farmers and other outdoor workers in the arid desert and valley regions of Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico and Texas – places where Coccidioides microbes thrive. Today, however, cases of cocci are found in more than 20 states.

“The most common thought is that you only get it if you work outdoors in a dusty area. I had an indoor job. I did retirement planning,” Purdie said.

Torrence Irvin also worked indoors – as a department store manager.

The climate crisis, increasing wildfires and dust storms may be fuelling the spread, according to research. Models of the projected spread of cocci predict a 50% rise in cases by 2100.

“It can happen to anyone. Wrong place, wrong time, and they just happen to breathe in spores carried by the wind,” UC Davis’ Thompson said. “In Central California, people get this infection just driving down the highway.”

By the time Irvin discovered Thompson’s Sacramento clinic in March 2019, he needed a walker to travel short distances. Thompson soon put Irvin on the experimental drug olorofim as part of a phase II clinical trial to test its impact on Coccidioides.

The drug is also being tested to treat Aspergillus fumigatus, the mould on WHO’s critical list.

“I’d never heard of valley fever,” Irvin said. “But Dr Thompson said we’re at the point where we’d exhausted any other option we had, so my wife and I were willing to try this.”

According to Thompson, if Irvin had not had the resources to find a specialist and change his treatment, “he probably would have died from his infection”.

“I worry even more for our patients with less resources who may have a really bad outcome or die because they aren’t seen by physicians who work with cocci and have access to cutting-edge treatments,” Thompson said. “We need more physicians to manage these patients, and we need to invest in the development of new drugs.”

Olorofim is a daily oral medication, meaning Irvin didn’t undergo invasive intravenous infusions other drugs may require during his more than three years of treatment, Thompson said.

“Torrence had no side effects at all, but a few others in the trial experienced liver toxicity,” he added. “But that generally could be managed by stopping the drug, restarting at a lower dose and then increasing it over time.”

Today, Irvin is now off olorofim, and repeat tests show no emergence of the disease. That could change, however.

“Dr Thompson told me I would always have some form of cocci in my body, based on the degree to which I had it,” Irvin said. “Still, I’ve gone from being on a walker to being on a cane, which was a huge improvement. It’s been a blessing.

“I’m still out of work for the disease, but I’m stronger,” he added. “I’m back in the gymnasium working out. I’ve regained a lot of the weight.”

The damage to his lungs, however, was extensive, leaving scar tissue that Irvin says keeps him from fully recovering.

“I wish I’d had listened to my body when I first got sick. If I would have responded more quickly to what I was going through, I may have been able to catch this before it went through my lungs.”

See more from MedicalBrief archives:

Cryptococcal fungi in public spaces in SA

Mould, the silent killer, under-reported and misunderstood

Threat of resistance to anti-fungal drugs under-recognised

UFS team probes deadly fungi that kill millions of people

WHO report urges more R&D for fungal diseases